Mar 4, 2022

Food prices climb to record as Ukraine war roils trade

, Bloomberg News

Farmers must plan differently as Russian attack weighs on food supply: Sylvain Charlebois

Global food prices jumped to a record last month, just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine started causing chaos in global crop trading that will likely push costs up even more.

A United Nations’ index of costs was already near a peak set in 2011 before the war disrupted exports out of the Black Sea region that’s known as the world’s breadbasket. Since then, grain and vegetable-oil prices have rocketed to fresh records or multiyear highs, piling more inflationary pressure on consumers and governments and threatening to worsen a global hunger crisis.

Global crop trading has been thrown into disarray as the war shuts Ukraine’s ports, and sanctions on Russia leave traders, banks and shipowners wary of doing business there. Before Russia attacked its neighbor, food prices were already on a tear on the back of unfavorable crop weather as well as an energy crunch and expensive fertilizers.

The UN’s World Food Programme on Friday warned about the consequences that the war in Ukraine will have beyond the country’s borders.

“It’s just tragic to see hunger raising its head in what has long been the breadbasket of Europe,” WFP Executive Director David Beasley said in a statement. “The bullets and bombs in Ukraine could take the global hunger crisis to levels beyond anything we’ve seen before.”

The UN’s food price index rose almost 4 per cent in February. Costs have surged more than 50 per cent since mid-2020, feeding through to prices at grocery stores. Much of the rally has been underpinned by gains in vegetable oils such as palm, which is used in about half of all supermarket goods.

The UN’s February reading only partly incorporated the impacts of the invasion of Ukraine. Since then, prices of key staples have spiked to records or multiyear highs.

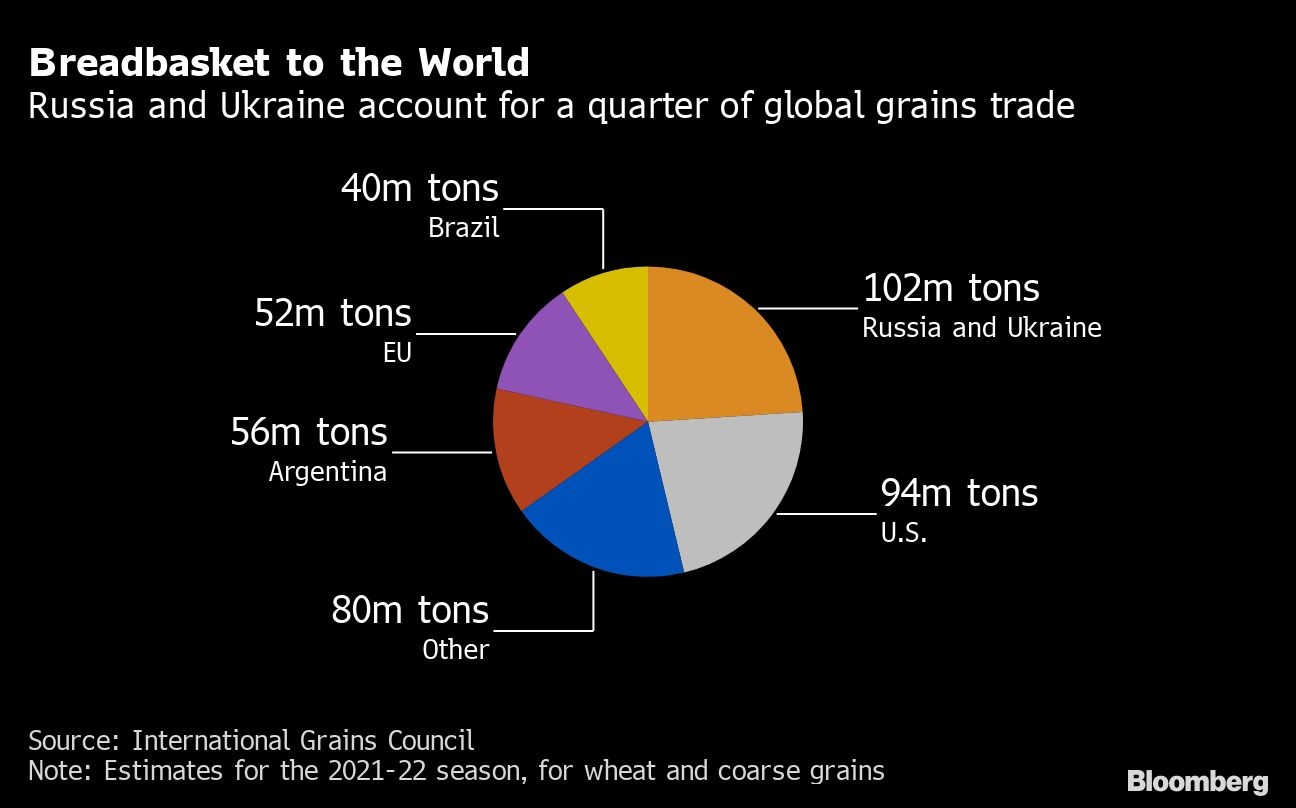

Russia and Ukraine play a crucial role in supplying food. Together, they account for about a quarter of all wheat and barley shipments, a fifth of corn and the bulk of sunflower oil. With big volumes of the region’s supply shut off, buyers are having to hunt elsewhere, though some importers are struggling to secure supplies in the face of high prices and few cargo offers.

“Concerns over crop conditions and adequate export availabilities explain only a part of the current global food price increases,” Upali Galketi Aratchilage, an economist at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, said in a report. “A much bigger push for food price inflation comes from outside food production, particularly the energy, fertilizer and feed sectors.”

Grain stockpiles remain at a “comfortable” level, although those high input prices risk curbing harvests in the future, he added by phone. The food-price gains are impacting average citizens worldwide and will be hardest felt across low-income countries where groceries make up a large chunk of consumer budgets.

The FAO is making a separate assessment of how the crisis in the Black Sea region will affect products like grain and aims to release a report mid-month, Galketi Aratchilage said.

Separately, the UN boosted its estimate for global grains trade by 2.7 million tons, highlighting that demand was already running hot before the Ukraine war curtailed supplies. The outlook doesn’t yet factor in the impact of the war, but the agency predicted Ukraine and Russia still had about 32.5 million tons of wheat and corn left to ship this season.

It’s unclear how much of that will now make it to the market.