Dec 13, 2022

For Debt Collectors Driving Fake Hearses, Business Is Booming

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the new recruits arrive at Ángel Jiménez’s debt-collection business in Santiago de Compostela, a picturesque medieval city in north-western Spain, they’re quickly schooled in the art of cajoling, nagging and prodding.

Then they’re handed a pin in the form of a small silver cross to attach to their lapels. That’s the finishing touch on the undertaker uniform.

Jiménez’s company is no ordinary debt collector. At least not by international standards. It’s one of a number of businesses that still resort to an age-old tactic in Spain when debtors refuse to pay up: public humiliation. Jiménez’s collectors will don the undertaker uniforms and head to the homes of the truly recalcitrant in fake hearses emblazoned with the name of the company — La Funeraria del Cobro, or Undertaker of Debt Collection — to try to shame them into coughing up the cash.

And in a sign of how surging inflation has rattled the economy in Spain, and across Europe more broadly, Jiménez is on a hiring spree. His clients — typically small business owners owed money by delinquent customers — are pressing him to recoup their funds at a faster rate. With annual inflation soaring to as high as 11% this year, their own business costs are climbing every month, creating a greater need for steady and timely cash flow. So Jiménez is adding 20 new debt collectors to his current team of 38.

“In this high-inflation environment, our clients need to make sure they can get their hands on cash,” Jiménez says.

These shaming tactics are illegal, and considered immoral, in many parts of the world — but not in Spain where slow-moving legal processes mean determined late-payers can hold out for a long time without being forced to settle what they owe. Or, viewed differently, it’s a system that actually creates the need for companies like Jiménez’s. That’s how he likes to see it. “We fill a gap in the market,” he says.

His fake hearses, to be clear, don’t get paraded out every day. It’s something of a last resort that Jiménez instructs his collectors to use only after more attempts to reach a negotiated solution have failed.

Jiménez says he mainly uses his fleet of funeral cars as a publicity tool to advertise the service he offers. More usually, his collectors will pay calls on debtors in ordinary vehicles carrying the La Funeraria livery. But the objective is the same — to shame debtors into coughing up what they owe by turning their non-payment into a public spectacle.

With higher living costs squeezing company and household budgets, the economic cycle is shifting in a way that’ll bring in more work for outfits like Jiménez’s, which has been chasing late-payers since 2001.

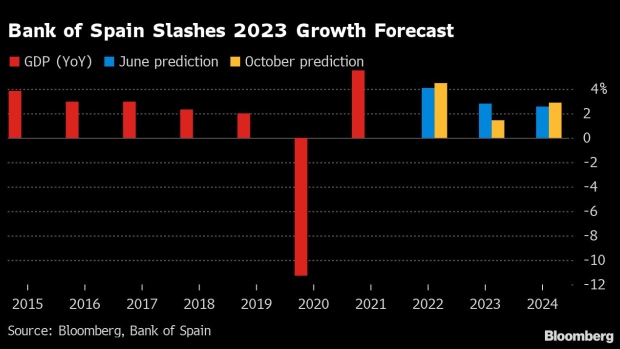

In October, the Bank of Spain halved its 2023 forecast for Spanish economic growth and lifted its inflation forecast for next year to 5.6% from the 2.6% it was predicting in June. Meanwhile, with interest rates on the increase, there can be more incentive for debtors to delay payment of bills rather than fund their businesses with pricier credit from banks.

La Funeraria isn’t alone in a Spanish costumed debt collection industry that also features monks, bullfighters and collectors decked out in tails and top hats. In all, Jiménez and his rivals in fancy dress account for just a small portion of the total debt-collection industry.

The boom in business they’re gearing up for, though, reflects broader trends facing lenders.

While higher borrowing costs swell margins for banks, they also crimp demand for credit and drive up bad loans. Defaults as a proportion of total lending could reach 4.5% next year from 3.9% this year and keep rising to 5.5% in 2026, according to the accounting and consulting firm EY.

Costumed debt collection firms were once common across the Spanish-speaking world, including in Colombia, which cracked down on the practice three decades ago. Peru, where some collectors dressed as “Hombrecitos Amarillos” or Little Yellow Men, also long since outlawed the activity, said Pere Brachfield, a lawyer and professor of credit and collection management at Barcelona’s EAE Business School.

The fact that they still exist in Spain is down to long-standing legal oversight, he said by phone.

“If some kind of practice is not expressly prohibited in Spain, then by default it’s tacitly allowed,” said Brachfield. “How can it be that in a country that has rules for everything, neither parliament or cabinet has got round to putting an end to this?”

--With assistance from Macarena Muñoz.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.