Nov 27, 2018

Ford gets left at the lights by General Motors

, Bloomberg News

If you’ve read Amy Goldstein’s searing account of the shuttering of a car plant (Janesville), you’ll know it’s a decision that has lasting human consequence. So while I wasn’t surprised that investors cheered on General Motors Co’s (GM.N) announcement that it will close seven plants and cut 15 per cent of the workforce, the plaudits still felt cold. Capitalism doesn’t do compassion very well.

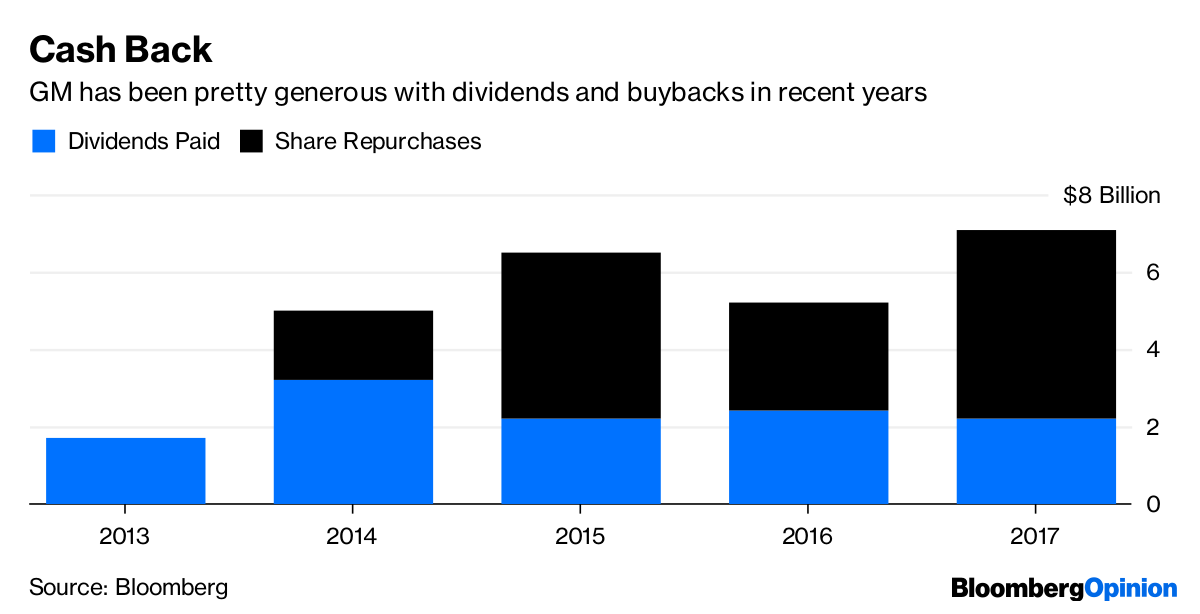

Cutting jobs so soon after the American taxpayer prevented GM from going under also seems ungrateful. That GM has spent US$25 billion on dividends and share repurchases over the past five years doesn’t exactly improve the optics.

Even so, there’s probably something in the view that this is a necessary, and proactive, down-scaling of GM’s production sites to prepare for some vast challenges ahead. These include a slowing U.S. car market, rising raw material costs and the shift to less labor-intensive electric vehicles.

GM would get no thanks if it sat on its hands today only to demand another bailout when the next recession hits, as it surely will. Hence, chief executive Mary Barra deserves some credit for trying to lower the point at which GM breaks even while the economy is still in reasonable shape. If only the same could be said for cross-town rival Ford Motor Co.

Ford was quicker to announce that it’s all-but abandoning car production to focus on more profitable SUVs and trucks. New boss Jim Hackett has also floated the idea for an US$11 billion multi-year restructuring plan to tackle the “ankle-weights” Ford is carrying around. So far, though, he’s given precious little detail about what this will entail, leaving shareholders disappointed and the workforce in limbo. The stock is languishing at levels similar to 2009 and the dividend yield is 6 per cent – a level that often indicates a payout cut is in the offing (Ford says it’s not.)

It’s probable that a big chunk of Ford’s cutbacks, when they're finally announced, will be made overseas – the U.S. accounts for most of its profit. GM has already been there, and done that. Barra has made deep cuts in emerging markets and handed off the Detroit giant’s struggling European business to Peugeot in 2017.

Evercore ISI analysts describe Ford’s approach as “much more drawn out, less detailed and lethargic.” They have a point. A press release published by Ford on Monday summarizing its “business transformation” efforts felt more than a touch defensive. Ford hasn’t always been so flat-footed. The painful restructuring it initiated in 2006, which included the pawning of the blue oval logo, meant that it didn’t have to go cap in hand to Washington when the recession hit soon after.

To be clear, life-changing job cuts shouldn’t be hurried, nor should they be accelerated just to appease shareholders hoping for a short-term return. Unlike GM, Ford has less to fear from activist investors because the founding family controls 40 percent of the voting rights. If Ford and Volkswagen AG can find a meaningful way to collaborate on future technologies or in under-performing markets, as has been reported, it’ll be worth the wait.

As always, though, there’s a balance to be struck between protecting workers and the financial health of the company. GM has shown where its priorities lie. Ford could use some of Barra’s decisiveness.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.