Nov 15, 2018

Four Ways GE’s Crisis Could Play Out

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- It would have been hard to imagine General Electric Co. erasing $200 billion in market value two years ago, but a series of accounting revelations, combined with weak demand for gas turbines and heavy debt, have made the unthinkable a reality.

The dramatic decline has investors asking themselves what the worst-case scenario could be as new Chief Executive Officer Larry Culp attempts a turnaround. Based on what typically happens to companies under financial duress, it’s easy to imagine four broad scenarios for GE, a 126-year-old company that traces its roots back to Thomas Edison’s efforts to profit from electricity.

Success

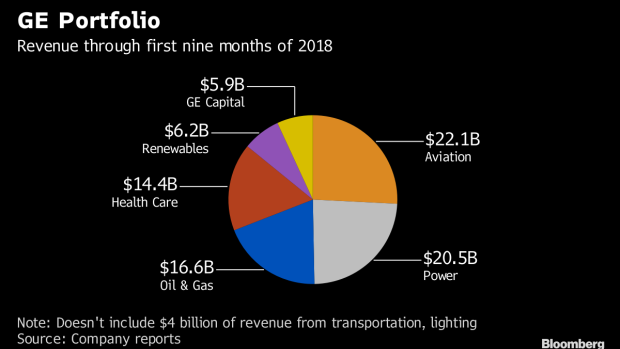

One possibility is that Culp swiftly succeeds in turning GE around arresting the share-price collapse. If all goes as planned, GE will be a smaller, simpler and more stable company with businesses that sell aircraft jet engines, power-generation equipment and wind turbines. Revenue growth probably won’t be spectacular and profit margins are likely to continue lagging industrial leaders such as Roper Technologies Inc. and 3M Co. But GE would have a shot at regaining a higher credit rating and reflating its dividend payment, helping to win back investors.

In a best-case scenario, Culp will sell assets, pare debt and further whittle down the finance business, GE Capital, without draining too much cash. A major challenge lies in fixing deep problems at GE’s marquee power division, which makes gas turbines. The company had to rely on price cuts to win orders after falling behind competitors Siemens AG and Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems on technology, said Karen Ubelhart, an analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence.

Under former CEO Jeffrey Immelt, GE doubled-down on the business with the $10 billion purchase of Alstom SA’s power assets just as demand for gas turbines softened and renewable energy gained a larger share of the electricity-generation market. Culp will have to work through those low-profit orders and baggage that came with Alstom, such as job guarantees to the French government.

He’s got plenty of incentive: If he can restore GE’s stock price to its level in late 2016, he would be in line for a windfall of more than $200 million.

Muddling Through

Under another scenario, Boston-based GE reaches a similar end state -- but only after a long, drawn-out slog.

Investors are concerned about the company’s debt load of more than $100 billion. GE’s bonds are trading like junk even though the company still maintains an investment-grade rating. Yields on notes issued by GE Capital International Funding with a 3.37 percent coupon and maturing in 2025 have climbed above 6 percent, which is more than the yield on a Bloomberg Barclays index of debt rated in the highest speculative-grade tier.

Investors have also been snapping up derivative contracts that protect against losses on GE debt, with five-year credit default swap prices spiking to above 200 basis points per year this week for the first time in years.

GE, which has had its credit grade cut by all three major ratings companies since early October to three levels above junk, faces “execution risks at both the industrial and GE Capital businesses related to numerous transactions and organizational changes,’’ Fitch Rating said Nov. 2.

A further reduction in GE’s credit rating would drive up borrowing costs. The company has $35 billion of bonds maturing from 2020 to 2022, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. GE has $20 billion in cash and more than $40 billion of credit lines to survive a liquidity crisis. But tapping those lines at higher interest rates would make it that much harder to reduce debt. GE declined to comment except to point out its liquidity sources and ability to tap the commercial paper market for working-capital needs.

Asset sales have to reduce debt by enough to offset the lost earnings from the divested businesses. That’s not always easy when buyers know a seller is highly motivated, said Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at New York University. How quickly GE can pare debt to a manageable level will depend on how quickly the Power unit can be stabilized, and on how well businesses such as aviation continue to perform.

Investors could be waiting a while.

“The liability side has the potential to very much be within GE’s control,” said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Joel Levington. “But even if you control that, you may not have enough earnings power after to make the leverage or the math work in terms of the BBB+ rating.”

Financial Failure

Nobody is predicting GE’s demise. The market, though, has seen giants fall before. Lehman Brothers and Enron are gone. General Motors went bust and survived thanks to a U.S. bailout. For GE, the stars would have to align against the company to push it into insolvency. An economic recession that undercuts GE’s healthy businesses and impedes a power unit turnaround, coupled with a larger-than-expected financial hole at GE Capital, would worsen the company’s plight.

GE’s latest slide “is not really about liquidity,” Steve Tusa, an analyst with JPMorgan Chase & Co., said in a Nov. 9 note. But he nevertheless painted a bleak picture for GE, saying the financial unit is burning cash at a rate of $3 billion as year and facing a backdrop of rising interest rates.

“It can get worse as the combination of higher rates and the coming wall of refinancing suggests another $900 million of headwind,’’ Tusa said in the report.

GE has a recent track record of negative surprises on liabilities. In January, the company announced a $6.2 billion charge at a long-term care insurance portfolio, plus a $15 billion shortfall in its insurance reserves that it would have to provide over seven years.

Another charge of $22 billion related to the power business was dropped on the market in October. The Department of Justice and Securities and Exchange Commission are both investigating GE’s accounting practices, raising uncertainty.

“Right now, we just can’t ring-fence them. We just don’t know,’’ said Bloomberg Intelligence’s Ubelhart, referring to GE’s liabilities. “The fear is just how big is that black hole.’’

White Knight

Even though GE is a shell of its former self, the company is still large. With a market value of more than $70 billion, it would take a whale of an investor to rescue the company. Warren Buffett, who provided GE an emergency loan during last decade’s financial crisis, springs to mind. A hand from the government -- similar to the auto bailout -- is very unlikely.

There’s also the possibility of a breakup, and the end of a U.S. business icon. GE has already said it’s planning to spin off its health-care business. Its sprawling aviation division, described by Culp as a “crown jewel,” would probably attract suitors or be able to go it alone. The fate of the troubled power unit is much harder to predict.

To contact the reporters on this story: Thomas Black in Dallas at tblack@bloomberg.net;Molly Smith in New York at msmith604@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Case at bcase4@bloomberg.net, Dan Wilchins

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.