Dec 12, 2022

FTX Bankruptcy Means $73 Million in Political Donations at Risk of Being Clawed Back

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- At least $73 million of political donations tied to Sam Bankman-Fried’s FTX may be at risk of being clawed back as bankruptcy lawyers sort through the remnants of his crypto empire in search of assets to repay creditors.

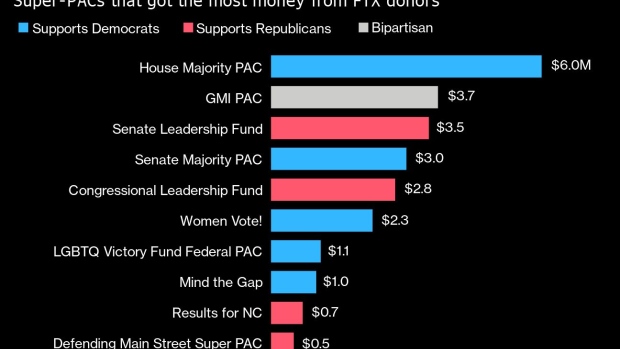

The wide-ranging contributions from Bankman-Fried and two of his top lieutenants, Ryan Salame and Nishad Singh, include more than $6 million to a super political action committee for House Democrats, $3.5 million for the GOP’s Senate Leadership Fund and $3 million for a fund that backs Senate Democrats.

Washington’s brief but intense flirtation with FTX donors as crypto executives sought to influence industry regulation may end up backfiring spectacularly, damaging the reputations of politicians who benefited from large contributions while some FTX exchange users face losing their life savings. Crypto billionaires — who came with millions in campaign cash — were able to convince many lawmakers that the nascent industry needed a light regulatory framework in order to innovate, but FTX’s implosion has now cast doubt on that.

It’s another layer to the fallout from FTX’s implosion. Just a few months ago, Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old founder of the crypto exchange, had pledged to give as much as $1 billion in the 2024 presidential election cycle and was touted by his supporters as the next George Soros. Salame had been donating to Republicans at almost the same pace as Steve Schwarzman and Peter Thiel.

“Nobody ends up looking great in this,” said David Primo, a political science professor at the University of Rochester. “FTX was so broad-based in their giving.”

While there’s precedent for forcing political entities to return contributions in cases of fraud, recovery prospects are unclear in FTX’s case. Recouping campaign funds as part of the bankruptcy proceedings is a complicated and lengthy process, and the scope of the total funds eligible for clawback depends on myriad federal and state laws. It is also subject to the bankruptcy lawyers’ judgment on what money, which may be long spent by the time the FTX trustees try to go after it, is worth the effort.

Bankman-Fried is facing additional scrutiny for recently saying he gave equally to Republicans and Democrats, but funded conservatives through “dark money” groups that don’t identify donors. The claim is almost impossible to verify unless the recipients voluntarily disclose they received money from him.

What’s clear from public records is that donors tied to FTX gave to Senator Mitch McConnell and Representative Kevin McCarthy, the top Republicans in the House and Senate. They gave to Hakeem Jeffries, now the Democratic Leader in the House, and Dick Durbin, a member of Senate Democratic leadership, in total doling out $73 million in federal races. Jeffries and Durbin have both said they donated money given to their campaigns to charity.

Apart from that, Bankman-Fried also gave to state committees. Texas Democrat Beto O’Rourke’s gubernatorial campaign said it returned a $1 million donation Nov. 4, one week before FTX declared bankruptcy. Bankman-Fried also gave $850,000 to the Emily’s List Non-Federal PAC, which helps state and local candidates.

Caroline Ellison, the former chief executive officer of Alameda Research, the Hong Kong-based sister trading company of FTX, didn’t make any donations at the federal level in the 2022 cycle.

One key factor for the scope of any attempt to recoup the donations is whether the court determines there was fraud or fraudulent intent involved in FTX’s collapse, according to Ilan Nieuchowicz, a litigator for law firm Carlton Fields. If so, nearly all the donations tied to FTX could be a target for recovery; if not, then only donations made within 90 days of the company going insolvent — a total of about $8.1 million — might be subject to recapture.

Some recipients of the largesse are trying to get ahead of the issue by moving proactively to give away donations.

Debbie Stabenow, a Michigan Democrat who received $20,800 from Bankman-Fried, says she plans to donate the money to a charity in her state. Senator John Hoeven, a North Dakota Republican, gave the $11,600 he received from Bankman-Fried and Salame to the Salvation Army.

Giving donations to charity rather than returning it to FTX is preferable for many lawmakers because it can win them points with their local communities, according to Ann Ravel, a former chair of the Federal Election Commission. “It makes them look better,” she said.

Politicians who donate an equal amount of money to a charity doesn’t extinguish the claims of fraud victims. The bankruptcy trustee could still ask that donations made by FTX donors be returned if courts determine Bankman-Fried and other FTX executives committed fraud.

The money FTX and its top executives gave directly to individual candidates for federal office only totals in the thousands because of contribution limits, amounts too small to be worth suing to recover. But the large donations to established super PACs — mostly the big fundraising operations for congressional Democrats and Republicans — are a more attractive target.

Of the $73 million Bankman-Fried, Salame, Singh and FTX corporate entities donated, $45.5 million, or 63% of that total, went to their own personal super-PACs, including Bankman-Fried’s Protect Our Future and Salame’s American Dream Federal Action. Salame backed Republicans, while Bankman-Fried and Nishad largely supported Democrats.

Most of the money from those entities has already been spent, paid to a long list of vendors to support various office seekers. Bankman-Fried’s PAC only had $384,588 cash on hand as of late November, the last time the entity was required to publicly report its finances.

But there are $26.6 million of contributions linked to FTX that went directly to other large super PACs, including those aligned with the House and Senate leadership of both parties.

Those groups are the easiest targets and most vulnerable to recovering the funds. They still have lots of money on hand, and will continue to exist, unlike some PACs controlled by single candidates or individuals that can close at any time. These entities will also take in millions in additional dollars ahead of the 2024 races.

Those recipients are unlikely to voluntarily return the funds. Unlike politicians, who could be attacked for keeping contributions from a disgraced donor, super-PACs face little political pressure, according to Charles Spies, who practices political law at Dickinson Wright.

“It’s a lot easier to return a symbolic $1,000 contribution than it is $1 million to a super PAC,” Spies said in an interview.

Representatives for the House Majority PAC, Senate Leadership Fund, GMI PAC, McConnell and McCarthy didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Campaign contributions have been clawed back by bankruptcy trustees before. In 2011, a district court judge ordered five party committees, including the Democratic National Committee and its Republican counterpart, to return donations totaling $1.6 million that they’d received between 2000 and 2008 from Allen Stanford, one of his top lieutenants and his Stanford Financial Group, which was part of a Ponzi scheme he operated until its collapse in 2009.

Though the party committees hadn’t known the money donated was part of the proceeds of a criminal fraud, they were ordered not only to refund the contributions but to also pay interest and the legal fees of the bankruptcy trustee. Dozens of campaign committees and political action committees that received smaller donations received letters requesting the money be returned. Of those, 43 disgorged donations totaling $162,250 while 39 held on to $117,700, according to a disclosure by the trustee.

“With contributions in the millions, the trustee has to pursue it,” said Kevin Sadler, an attorney with BakerBotts LLP. He sued the party committees on behalf of Stanford’s victims.

Going after the political donations is likely to be one of the final stages of FTX’s bankruptcy case, said Joseph Acosta, a bankruptcy partner at law firm Dorsey & Whitney LLP. It could be years away because of how incomplete the books and records for the company are, he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.