Jun 10, 2021

G-7 leaders poised to turn spotlight on climate finance

, Bloomberg News

China is in the room whether they are physically there or not: Former White House economic official

The world’s richest governments are under mounting pressure to help poor countries fight climate change. At the Group of Seven summit in the U.K., they’ll get a fresh chance to do something about it.

Leaders of the G-7, including U.S. President Joe Biden and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, are meeting in Cornwall, England through Sunday. On the agenda is a discussion of how to help finance a shift to cleaner energy in low-income countries.

Observers are looking for a pledge from the group to steer the recovery from the pandemic in a greener, fairer direction. A draft document seen by Bloomberg News ahead of the summit includes a commitment for each G-7 member to increase its financial contributions to help the poorest countries decarbonize. Specifics are still under discussion. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is expected to announce new funding, according to a person familiar with the matter.

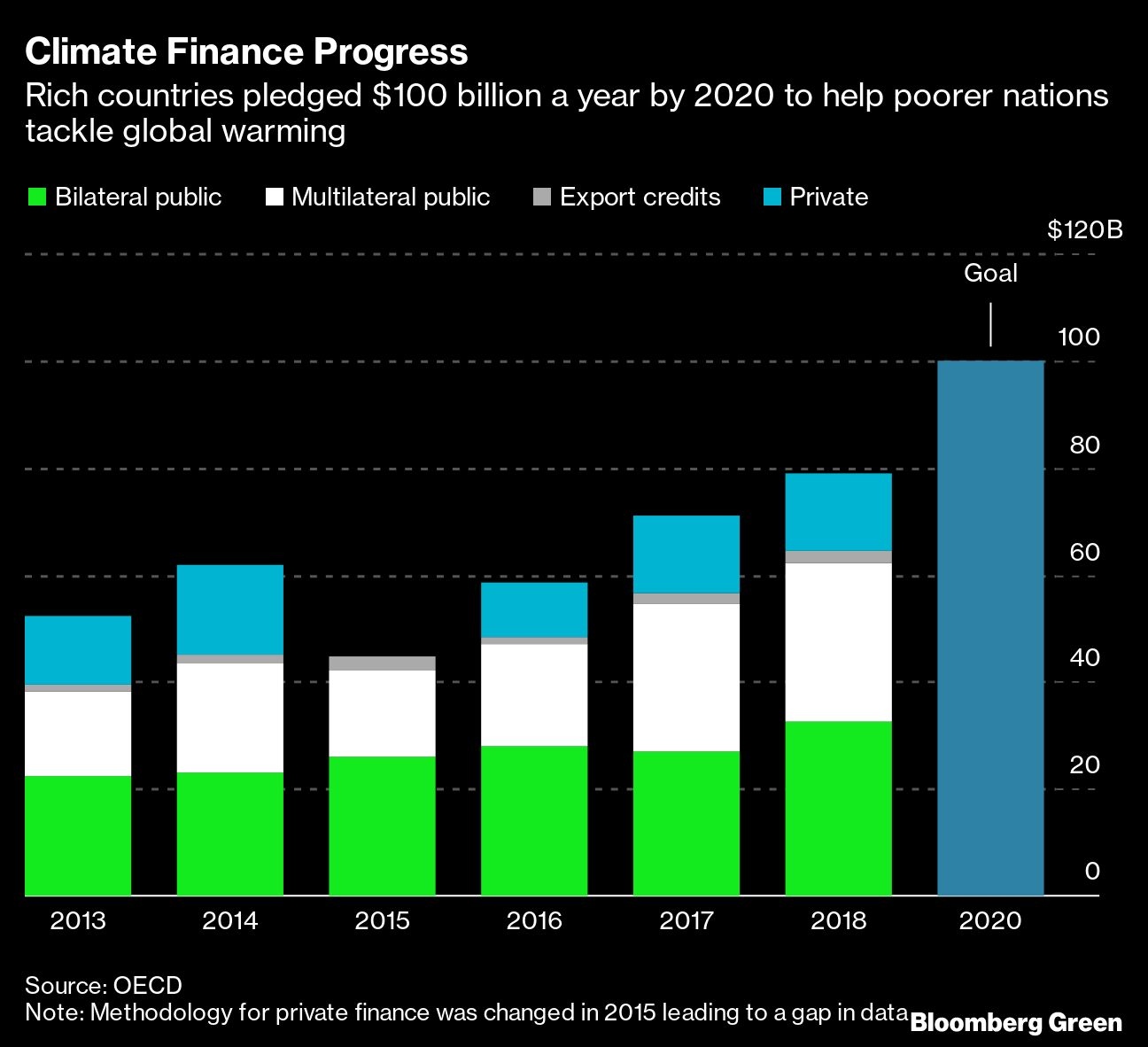

In 2009, developed countries pledged to collectively devote US$100 billion annually to climate transition in poorer countries by 2020. The latest data show they’ve so far failed to make good on that promise.

Concrete action this week could rally other countries to step up their ambition at this year’s U.N. climate change conference, scheduled to be held in Glasgow in November. The aim, affirmed in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, is to put the world on a path to limiting global temperature increases to less than 2-degrees Celsius, striving for 1.5 degrees if possible.

“Ahead of COP26 in Glasgow, it is important that the most advanced economies send an ambitious message on climate and energy issues,” said European Union Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson. “I expect to see a clear signal from the G-7 summit on the commitment to net zero and a push for accelerated action towards decarbonizing our power systems.”

Why it matters

The question of who pays to tackle climate change lies at the heart of global action. Poor countries say they need funding if they are to invest in the technologies needed to wean themselves off fossil fuels, while also dealing with the worst impacts of global warming, such as rising sea levels and heat waves.

Rich countries -- many of which were able to develop over the last century while spewing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere -- agreed to help pay via their US$100 billion-a-year commitment, made during a 2009 UN climate summit in Copenhagen.

This year, all nations are supposed to set enhanced national climate goals in a bid to avoid a climate catastrophe. But some countries have said more needs to be done to help developing countries meet their targets. At a White House summit in April, leaders of Indonesia and Bangladesh were among those who called for additional support.

What has been promised?

Climate finance mobilized by developed countries reached US$78.9 billion in 2018, far short of the US$100 billion agreed, according to the latest data from the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. The funding comes from a mixture of sources, including private and public institutions.

Donor countries and multilateral development banks are under pressure to ensure that half of the money goes into adaptation, or adjusting to climate change, not just cutting carbon emissions. At the moment, just a fifth of the funding goes to adaptation and resilience.

Why they are failing?

Few rich countries have set out their plans to increase climate funding for low-income nations. The U.K., Luxembourg and New Zealand are the only three nations to announce planned multi-year increases in their climate finance, according to a report by Care Denmark. The non-profit concluded that international funding would increase by just US$1.6 billion in 2021 and 2022, compared to the amount in 2019.

To show a clear commitment, G-7 leaders must jointly accept responsibility for reaching the US$100 billion goal, while also individually promising to double their finance pledges, said Eddy Perez at Climate Action Now Canada. Countries also need to announce new donations at the summit, he said.

What’s America’s role?

Under President Barack Obama, the U.S. pledged to provide US$3 billion to the Green Climate Fund, a UN program to help developing nations transition to clean energy. However, the country paid only US$1 billion of that before Donald Trump took office in 2017 and curtailed contributions. He also withdrew the U.S. from the Paris accord, which Biden later rejoined.

In April, Biden pledged to spend US$5.7 billion annually by 2024 to help with climate financing. Environmental activists said the commitment falls short of the US$8 billion to US$800 billion needed through 2030.

How has this been affected by COVID?

After the pandemic rattled the global economy, low-income countries found it even more difficult to attract investment. The real test for G-7 leaders will be how they’ll support green and fair global recoveries, according to Jennifer Tollmann, a senior policy adviser at the E3G environmental think tank.

“Will they cement credibility by agreeing common and ambitious climate goals for their own recoveries?” she said. “And will they deliver for international partners, particularly the world’s poorest?”

Plans by Biden and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson to rally the richest economies to provide vaccines to low-income countries could also help rebuild trust undermined by the West’s failure to deliver on climate finance. The U.S. intends to buy 500 million doses of Pfizer Inc.’s vaccine to share through an international program that could help poorer countries. Johnson has called for vaccinating the world by the end of 2022.

What will the G-7 do?

The draft document promises more funding to help the developing world cut carbon emissions, but the details still aren’t clear and nothing has been officially agreed. One potential initiative expected to be discussed at the summit is the “Clean Green Initiative,” an alternative to China’s Belt and Road infrastructure strategy, two people familiar with the matter said last week.

The leaders are also set to build on a May pledge by G-7 environment and climate ministers to coordinate efforts to curb emissions in energy-intensive sectors like steel, cement and chemicals. Cooperation among the richest countries would speed the shift to net-zero industries and lower the cost for the rest of the world, the ministers said.