Oct 11, 2021

Global Energy Crisis Piles Pressure on Aluminum Supply

, Bloomberg News

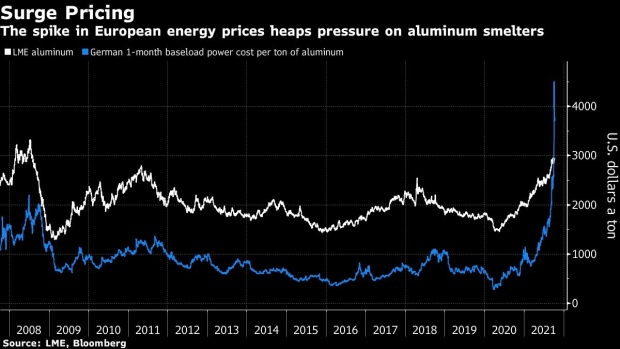

(Bloomberg) -- Aluminum has already jumped 50% this year, but some investors are now betting on an even bigger spike. The metal used in everything from beer cans to iPhones is massively energy intensive, and surging power prices are heaping pressure on supply.

Industry insiders like to joke that aluminum is basically “solid electricity.” Each ton of metal takes about 14 megawatt hours of power to produce, enough to run an average U.K. home for more than three years. If the 65 million ton-a-year aluminum industry was a country, it would rank as the fifth-largest power consumer in the world.

That meant aluminum was one of the first targets in China’s efforts to curb industrial energy usage. Even beyond the current power crisis, Beijing has placed a hard cap on future capacity that promises to end years of over-expansion and raises the prospect of deep global deficits. Now, with energy costs surging across Asia and Europe, there’s growing risk of further supply cuts.

Aluminum rose as much as 1.6% to $3,014.50 a ton on the London Metal Exchange Monday, the highest since July 2008.

For investors looking to bet on a future price spike, London Metal Exchange options contracts offer a popular and low-risk way.

In recent weeks, investors have been buying calls with strike prices of up to $4,000 a ton, according to traders active in the market -- effectively betting that prices could move significantly beyond that level to reach new all-time highs.

“It feels very much like a structural hedge-fund play,” said Keith Wildie, head of trading at Romco Metals, who’s been trading LME options for more than 20 years. “What they’re positioning for is a significant market dislocation, and a sharp move higher in the price.”

A number of aluminum plants in China are being mothballed and the country’s production has probably peaked, at least in the short term, said Mark Hansen, chief executive officer at London-based trading house Concord Resources Ltd. With the market in a deficit and needing to stimulate investment in new production outside China, prices could hit $3,400 a ton in the next 12 months, he said.

As the global metals world prepared to gather in London for the annual LME Week, signs of pressure on the aluminum industry have continued to mount. China’s State Council announced Friday it will allow higher power prices in a bid to ease the worsening energy crunch. In the Netherlands, aluminum producer Aldel will curtail production from this week production due to high electricity prices, Dutch Broadcaster NOS reported.

Next, traders and analysts say investors are watching for a possible hit to Chinese aluminum exports. With its own production under pressure and demand booming, the country has been importing ever-greater quantities of primary metal. However, it’s still exporting huge volumes of semi-finished aluminum, in part supported by tax rebates.

“Given the acuteness of the power shortages and the curtailments we’ve seen, it just doesn’t seem rational for China to be exporting that volume of aluminium products every single month,” James Luke, commodities fund manager at Schroders, said by phone from London. “It’s essentially just a net export of energy resources.”

Analysts including at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. say there’s potential for Beijing to lower or remove the value-added tax rebates on exports to slow the flow of metal beyond its borders. With China likely to continue importing huge volumes of aluminum next year, that could leave the rest of the world desperately short, and raises the risk of a violent price spike.

This year’s surge in aluminum prices would typically prompt producers elsewhere to reopen old plants and consider adding new supply. Yet the even-bigger jump in power costs is putting pressure on smelters and may make restarts difficult.

As an example, if a smelter in Germany was exposed to one-month baseload rates for power, it would need to pay about $4,000 for the energy needed to produce a ton of metal, far outstripping current aluminum prices.

“The global metal market in 2022 will be the tightest it’s ever been,” Eoin Dinsmore, head of aluminum primary and products research at CRU, said by phone from London. “The rest of the world cannot deliver these quantities to China indefinitely.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.