Jun 22, 2019

Global Population Could Peak Sooner Than We Think

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since the days of Thomas Malthus, we’ve worried that overpopulation is about to overwhelm our planet.

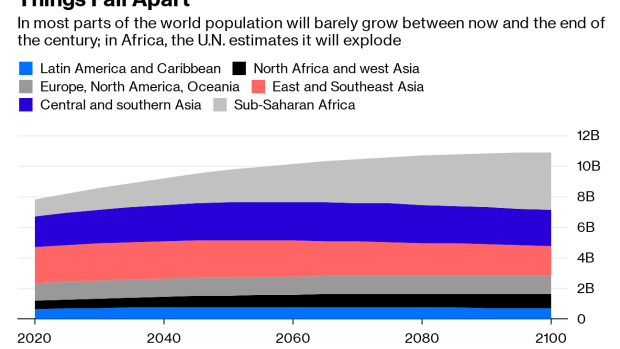

Those fears haven’t gone away. A further two billion people will be added to the current world population of 7.7 billion by 2050, the United Nations Population Division said in a report this week. Numbers will still be rising as the total approaches 11 billion people in 2100, according to the UN’s central forecast.

Agricultural productivity has confounded Malthus’s predictions by keeping the world’s population well fed despite its headlong growth in the past century. Still, a further 40% increase in the number of humans would put fresh pressure on the globe’s 33 million square kilometers of agricultural land – not to mention a climate that’s already at risk from population levels.

At the same time, signs are starting to emerge that this picture may be too pessimistic. Malthus’s key error was his failure to foresee how fertility rates would fall with increasing incomes – and the pace of change on that front has been staggering in recent years.

While India is forecast to overtake China as the world’s most populous country around 2027, its number of inhabitants will start to level off by mid-century thanks to a fertility rate that’s already fallen to 2.24 births per woman, around where Ireland was in the late 1980s. By 2025 the rate will fall to 2.14, roughly the levels at which population hits a steady state.(1)

Other large countries in Asia have seen even sharper declines. The rate of 2.05 in Bangladesh is already below where it was in the U.S. during the mid-2000s. Thailand’s 1.53 is barely higher than Japan’s, at 1.37. Of the world’s top 30 countries by population, 19 are already around or below replacement-level fertility.

The exception is sub-Saharan Africa. More than half the growth the UN expects to see in the global population up to 2050 will happen there. From about one-seventh of the world’s population at present, the region will grow to account for a fifth in 2050, and a third in 2100, according to the latest forecast. In Nigeria, where the fertility rate is 5.4, there are about 43 million women between the ages of 15 and 45, and a further 43 million who’ll hit child-bearing age by the mid-2030s.

Bullish expectations for African population growth depend on the idea that the region is fundamentally different from the rest of the emerging world. Demographic transition – the process whereby countries switch from high to low fertility rates as they urbanize and women get better access to education, contraception and employment – is expected to play out there in a unique way.

While most Asian, Latin American and Middle Eastern countries took about two decades to make the transition to fewer than three children per woman from more than five, the UN expects sub-Saharan African countries to take almost twice as long. Indonesia made the switch in just over 16 years; Tanzania is expected to take about 50.

Is that forecast right? There’s reason to think that after overestimating the pace of African fertility decline in previous decades, demographers are now underestimating it. If most countries in the region haven’t started a steep drop yet, it’s plausible that in most cases it’s because most countries have only just hit the sub-five levels at which the process starts to gather pace. Those that reached that point early, such as Botswana, South Africa, and Kenya, seem to be transitioning at a similar pace to countries elsewhere.

Sharp improvements in infant mortality also suggest a change may be around the corner. One tragic reason that African women have so many children is that so many of them die before their fifth birthday. But there’s now only a handful of countries where the chance of that happening is higher than 8%, roughly the level at which fertility rates start to fall.

Fewer infant deaths and mouths to feed will mean less heartache and stress for African families. At the same time, a proportionately larger working-age population will help generate the “demographic dividend” experienced by other countries at their most rapid stages of development, a boon that some analysts have feared Africa may miss out on. Beyond that, population growth more in line with the rest of the world will put less pressure on the planet’s climate and farmland.

To be sure, fertility rates are unpredictable. The availability of contraception in west and central Africa is still shockingly low by global standards, as is female education; 31 of the 39 countries where less than half of girls enroll in secondary school are in sub-Saharan Africa. Healthcare improvements can be reversed, too, while chaos and conservative social policies can cause birth rates to spike, as has happened in Egypt since the Arab Spring.

Still, those who fear a Malthusian outcome for the world’s population should think twice. Shrinking families confounded his grim predictions about the world’s future. The same may go for our current forecasts.

(1) There tends to be a time lag between the moment a country hits this replacement-level fertility rate and peak population, since babies born at higher fertility rates will still be having their own children decades after the overall level has declined.

To contact the author of this story: David Fickling at dfickling@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.