Oct 4, 2019

GM strike ripples across economy, raising fresh recession fears

, Bloomberg News

Linamar says U.S. auto strike estimated to impact earnings by $1M per day

Here in the heart of America’s car industry, car parts have nowhere to go.

Eighty-five tractor trailers full of hoods, bumpers and other assorted parts sat, unloaded, in Lansing, Michigan, this week -- more evidence of the cost of the General Motors Co. strike that has shut down most of its North American plants and idled 46,000 workers.

Soon to enter its fourth week, the strike is rippling across the economy, from parts suppliers in Michigan and Canada to bars, restaurants and other businesses that serve employees who now find themselves tight on cash. The layoffs have added to fears that a weakened manufacturing sector could tip the economy into recession -- potentially playing a role in next year’s election especially in a swing state like Michigan.

“It’s a necessary strike but everyone is feeling the hurt,” said Mike Luna, a warehouse worker and a chairman of UAW local 652, which is made up of striking GM workers and many laid off supplier employees.

Luna works at a Ryder Integrated Logistics warehouse, where about 500 workers have been laid off, leaving the semi-trailers in the parking lot. They are chock full of auto parts destined for one of two nearby GM plants: Hoods and painted body panels for Chevrolet Camaros; and hinges, hubcaps and exhaust systems for Cadillac sedans, Buick SUVs and Chevys.

The automaker itself has already lost more than US$1 billion in earnings before interest and taxes, according to one analyst estimate. GM’s bigger parts suppliers are losing as much as US$2 million a day by the same measurement. Workers at smaller parts makers across the U.S. are sending employees home.

In Michigan, parts workers furloughed by the walkout do not get strike pay and just this week began receiving state unemployment benefits that max out at US$342 a week -- not enough for most of his co-workers to live on, Luna said. Striking workers at GM get even less from the UAW’s rainy day fund, just US$250 a week.

Recession Concern

The strike comes at a potential inflection point for America’s economy. New statistics this week showed a sharp drop in U.S. manufacturing in September.

The GM strike isn’t helping. It’s chopped $400 million in direct wages out of the U.S. economy, with half of that loss coming in Michigan, Patrick Anderson, chief executive officer of Anderson Economic Group in Lansing, estimated. The U.S. Treasury has lost US$154 million so far just in payroll and income taxes.

In the southeast Michigan economy, a factory-heavy region, the layoffs have shaved off 1.8 per cent of earned income, he said. If that trend lasts for a quarter, “The chances of southeast Michigan going into a recession are pretty high,” Anderson said in an interview.

The impact stretches beyond Michigan. Canadian components maker Linamar Corp., which makes metal parts for drivetrains like camshafts and transmission cases, said Wednesday the sudden drop in GM orders is costing it up to one million Canadian dollars (US$750,000) a day in lost revenue. Shares of the supplier slid as much as 13.8 per cent Thursday to a six-year low.

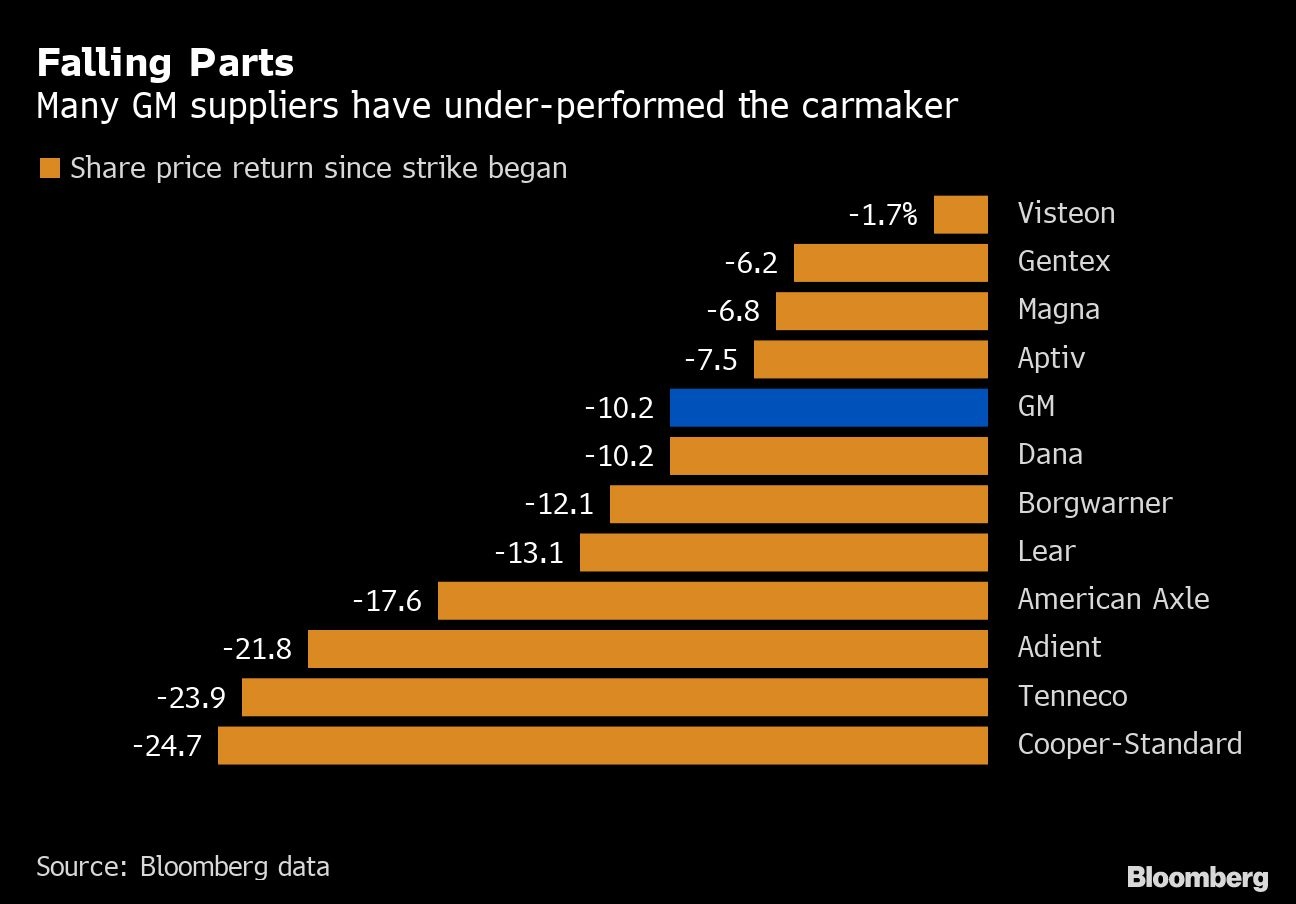

The walkout has forced American Axle & Manufacturing Holdings Inc. to lay off workers at its largest driveline plant in the U.S. The company, which was spun off from GM in 1994, still relies on the automaker for 39 per cent of its revenue. Chief Executive Officer David Dauch told Bloomberg last week his company may adjust its full-year earnings outlook if the strike continues for “an extended period of time.” Its stock has fallen 18 per cent since the labor action began on Sept. 16.

Lost Profit

The strike is costing Axle and Lear Corp., another big supplier, US$2 million a day each while the toll on parts-maker Tenneco Inc. is US$1 million daily, said RBC Capital Markets analyst Joseph Spak.

GM and its suppliers can make up some production once the strike ends, but not all of it. So some profit will either be lost or shifted to next year.

“We are getting to the point where it will be difficult to recover the lost production this year,” Spak wrote in a research note. “In some respects, that makes the remainder of 2019 somewhat of a throwaway for the group and could shift the focus to 2020.”

From the union’s perspective, GM turned out record profits over the life of the expired four-year deal and Chief Executive Officer Mary Barra made more than US$66 million. It wants a pay raise, especially for newer employees who start at less than US$20 an hour, and a clear path for temporary workers to become full-timers making US$30 an hour.

GM is looking to hold costs down, arguing that its current total compensation package of US$63 an hour is already more than that offered by Ford Motor Co., Fiat Chrysler and the Japanese plants in the U.S.

While the two sides wrestle over those and a few other issues, furloughed parts workers struggle to make do. At Ryder and most of the smaller suppliers, workers make around US$15 an hour. Union leader Luna said he cautioned workers a year ago to save for the strike. But at that wage, which equates to US$31,000 a year without overtime, many workers live check to check.

Some employees have gone to the United Way and other charities for help with buying food and other essentials, he said. A few have applied for new jobs, but that’s a tough sell.

“They are trying to get work,” Luna said, “but then you have to tell an employer that when the strike ends, you would go back.”

--With assistance from Chester Dawson.