Apr 22, 2022

Governance experts blast lack of 'skin in the game' in boardrooms

There’s an empirical relationship between share ownership and effective governance: Richard Leblanc

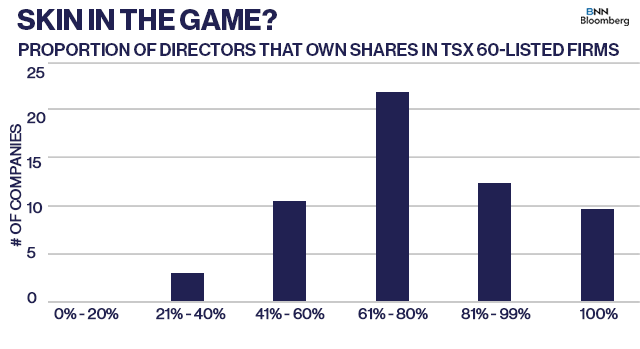

Most of Canada's largest publicly-traded companies have at least one director who hasn't personally invested in the company they help to oversee, according to a BNN Bloomberg analysis.

More than 80 per cent of all companies in the S&P/TSX 60 Index, the basket of 60 large-cap firms that is designed to reflect the S&P/TSX Composite Index’s sector weightings, have at least one current director on their board who hasn't made a personal investment in the company’s common shares, based on a review of the most recent information circulars provided to shareholders ahead of annual general meetings.

While there are no rules that require directors to buy stakes in companies they oversee, some governance experts believe doing so better aligns them with the long-term interests of the corporation and its shareholders. Many companies have ownership requirements for their directors to achieve by a certain date, but often compensate those directors with stock awards — typically referred to as restricted or deferred stock units (DSUs) — instead of a cash salary.

That lack of director investment is not unique to Canada. It was recently highlighted by Tesla Inc. Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk, the world's richest person, in a tweet where he criticized Twitter Inc.'s directors for their minimal ownership of the company's stock.

Musk's criticism comes as he pursues a potential US$43-billion takeover of the social media platform.

In Canada, the broad lack of personal investments by directors should not be overlooked by investors eyeing large Canadian companies, experts say.

"If you have too little skin in the game, you're not motivated to act in the best long-term interest of the corporation," said Catherine McCall, executive director of the Canadian Coalition for Good Governance (CCGG), in an interview.

In 2017, CCGG released a white paper outlining a set of four principles for boards to consider when structuring director compensation, highlighting share ownership as a key tenet that directors should abide by.

"Minimum formal shareholder requirements for directors (achievable over a predetermined time frame) establish and maintain an alignment of interests between directors and shareholders by requiring directors to have a meaningful investment in the company," the paper said.

Richard Leblanc, who teaches governance, law and ethics at York University, said that over time each director should ideally own at least three times their retainer in the form of shares.

"There is no legal requirement for a director to own shares," he said. "Activist investors, including Musk, however view this as a lack of confidence in the company on whose board you serve."

The information circulars show only 10 of the TSX 60-listed companies — four of which are among the Big Five banks — report that all of their directors have purchased common shares in the firms they help to govern. Fourteen of the TSX 60 companies had yet to file their 2022 circulars prior to this story originally being published, thus their 2021 circulars were used in the analysis.

The most recent circulars for eight of the TSX 60 companies (Restaurant Brands International Inc. (RBI), Thomson Reuters Corp., Hydro One Ltd., Dollarama Inc., Imperial Oil Inc., Magna International Inc., CAE Inc., and Power Corp.) show more than half of their directors hadn’t made personal investments in common shares of the company whose board they sit on. Of those eight, information for RBI, Dollarama and CAE was obtained from their respective 2021 circulars.

BNN Bloomberg reached out to all eight companies to request comments on the lack of personal investments.

Representatives from each company responded, all of whom shared a similar perspective: giving directors DSUs instead of a salary is the best way to economically align their interests with the company's shareholders.

"There are no legal requirements nor corporate governance guidelines which require that such alignment be achieved through market purchases," said Tracy Fuerst, vice-president of corporate communications and public relations at Magna, in an emailed statement. "Deferral of directors’ equity compensation is a recommended corporate governance best practice which succeeds in promoting alignment with shareholders since the value of each DSU corresponds directly with the value of a share."

Fuerst added that scrutinizing whether a corporate director has purchased shares on the market is a "red herring" and that deferring equity as compensation is the less risky method of preserving value for board members.

While there are many factors that can influence a company's share price, especially in a year that has seen a myriad of geopolitical and industry issues weigh on Corporate Canada, companies with fully-invested boardrooms have outperformed.

The average annual share return for the 10 TSX 60-listed companies where all directors have made a personal investment in the company is 36.1 per cent, more than double the 14.8 per cent return found for the group of eight firms where more than half of directors haven't invested into the company.

McCall said while DSUs may provide a good balance for director compensation, they may not share the same economic value because paying taxes on those stock awards is deferred until the board member leaves the company.

"[DSUs] are not equivalent to common shares, which you've purchased with after-tax income," she said. "So, in that sense, common shares would be superior to those equity instruments being counted like DSUs."

Leblanc also doesn't believe DSUs are a good proxy for directors to own a piece of a company.

"Being awarded shares on the basis of service as a director (without a connection to share price I might add) is not the same as actually purchasing the shares from a director’s savings," he said in an email. "I would say that boards would be wise to ensure at a minimum that each director owns a meaningful investment in the company on whose board they serve."

McCall noted one shortfall of requiring directors to have more skin in the game is that it could restrict board membership to the wealthy, rather than adding candidates who offer a more diverse skillset.

"We have to remember that one of the goals of board composition is to create a diverse board," she said. "If you have the expectation that directors are using their own wealth to purchase shares, rather than being compensated through DSUs, for example, you are restricting the pool of who your potential directors are to only wealthy individuals."