New US Home Sales Jump to Highest Level Since September

Sales of new homes in the US bounced back broadly in March as an abundance of inventory helped drive prices lower.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Sales of new homes in the US bounced back broadly in March as an abundance of inventory helped drive prices lower.

Hong Kong developer Lai Sun Development Co. is considering options for a planned office tower in the City of London, including a potential sale of a stake in the project.

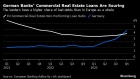

Germany’s financial regulator BaFin is taking a closer look at the real estate used by lenders to secure covered bonds known as Pfandbriefe, a €400 billion market traditionally considered among the safest in credit.

Taylor Wimpey Plc is failing to see lower mortgage rates translate into higher levels of home sales and is maintaining its forecast for fewer deals in 2024.

Chinese mainland investors increased their portion of total turnover of Hong Kong stocks to a record daily average in April, with the latest measures to bolster the city’s position potentially boosting their purchases.

Jun 14, 2021

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- New Zealand Finance Minister Grant Robertson added house prices to the central bank’s monetary policy remit despite both the bank and the Treasury Department advising it would have little impact.

Emails released to Bloomberg under the Official Information Act show Treasury considered the change useful only as a signal, and did not expect it to significantly influence monetary policy or house prices. Correspondence between senior Treasury and Reserve Bank officials also reveals the central bank fought a running battle over the language used in the new remit, insisting that it note the government’s desire for “sustainable” rather then “affordable” house prices.

Robertson pushed through the remit change earlier this year over the objections of RBNZ Governor Adrian Orr, prompting financial markets to drive up the kiwi dollar and bond yields as they saw it reducing the chances of further monetary easing. At the time, Robertson was under pressure to do something about house prices, which soared after the central bank slashed its official cash rate during the pandemic.

The government and the RBNZ have since implemented a range of measures that are expected to cool the housing market, from tax changes to tighter mortgage lending restrictions.

But the emails show the change to the remit, which Robertson proposed on Nov. 24 and confirmed on Feb. 25, was never expected to prompt the Monetary Policy Committee to run a tighter policy than it otherwise would have to slow house-price inflation.

“Attempting to use monetary policy to change the long-run level of house prices would require a persistently higher level of interest rates than warranted by the MPC’s economic objectives,” Treasury wrote in a draft report for Robertson circulated among officials in January.

“At most, we would expect that the MPC would only mitigate the extremes of the interest rate cycle,” it said. “Even then, if that entailed significant trade-offs with their economic objectives, then the requirement to have regard to house prices is unlikely to result in a significantly different monetary policy stance.”

That echoes Orr’s argument against the change published in early December. He said it would likely have only a limited impact on house prices given the primacy of the RBNZ’s employment and inflation goals, and that if the bank did act on house prices, it may result in higher interest rates, lower employment, below-target inflation and a higher exchange rate.

‘Limited Impact’

Treasury Secretary Caralee McLiesh came to a similar view.

“I agree that consideration of house prices is more likely to be effective through financial policy than monetary policy, given the alignment between stable house prices and financial stability, and the potential conflict between moderating house prices and achieving inflation/employment targets,” she wrote in a Jan. 18 email to a senior Treasury staffer.

“I expect the proposed changes to the MP remit would have only a limited impact on house prices (and other outcomes), although it does send a signal that government would like more awareness/visibility of secondary consequences of monetary policy.”

Bloomberg asked Robertson last week why he made the change to the remit knowing Treasury and the RBNZ didn’t expect it to have a significant impact on monetary policy.

He said it was to give the bank “the clear direction to understand and consider the government’s policy” and would “ensure that the issue of achieving sustainable house prices was clearly identified” as part of the MPC’s considerations.

Asked whether he expected the change to alter the RBNZ’s approach to monetary policy in any way, Robertson said: “That will depend on the way the Reserve Bank makes its decisions. The changes we put in place require the Reserve Bank to take account of what the government does and gives them the opportunity to understand our policy while working towards the bank’s objectives.”

The new remit, which took effect on March. 1, says the bank should assess the effect of its monetary policy decisions on the government’s policy as set out in a new subclause. The emails reveal the RBNZ fought hard over the language used in that subclause. It was strenuously opposed to the use of the word “affordable” housing, and insisted it should be “sustainable.”

‘Unfortunate Choice’

Orr described affordable as an “unfortunate choice of wording” in an email to RBNZ staff.

One of those staff members set out the RBNZ’s objections to the word in an email to colleagues on Feb. 11. Affordable was not well defined and not anchored to an economic modeling approach, while sustainable was “much closer to our financial stability mandate, where our concern relates to excessive volatility in house prices,” he wrote.

“Sustainable also has a much longer-term orientation, whereas affordable gets us much closer to the idea of targeting house prices,” the official said. “We think that affordable is significantly inferior, and that we should push back against this suggestion.”

In the end it was a compromise proposed by the RBNZ that carried the day. The final wording was: “The Government’s policy is to support more sustainable house prices, including by dampening investor demand for existing housing stock, which would improve affordability for first-home buyers.”

The RBNZ signaled last month that it may start to raise interest rates in the second half of next year, but its forecasts suggest the tightening will have nothing to do with house prices. By that time, house-price inflation will have slowed to almost zero, the forecasts show.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.