Dec 3, 2019

Greece’s Ancient Power Is in Crisis on Climate-Cost Collision

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Outside a city that once vied with Sparta in ancient Greece, giant excavators are grinding away vast chunks of the rocky landscape to get at a form of energy that’s now becoming a risk to the country’s future.

Legend has it that Megalopolis was where Zeus smote the Titans because the ground was known to smolder as if struck by the god’s lightning bolts. The reality is that the area in the southern Peloponnese region, like parts of northern Greece, has an abundance of lignite -- a soggy form of coal that’s a major energy source for the country’s modern economy.

But in the age of global warming, the cost of pollution permits for burning the dirtiest fossil fuel has turned these aging power plants into money pits. The indebted state-owned Public Power Corp. SA will spend as much as 300 million euros ($330 million) this year to operate lignite facilities, compared with 200 million euros in 2018.

The dilemma is so bad that Greek officials say it would cost PPC less to pay workers to stay at home rather than produce at the most outdated facilities.

That puts Greece in a Catch-22. Shutting down the plants could starve the fragile economy of power, but the country -- still recovering from its debilitating debt crisis a decade ago -- can ill afford the money required to overhaul its electricity sector.

In a plan approved by cabinet last week, Greece’s government estimates that 44 billion euros in public and private investments will be needed over the next decade to meet its climate and energy goals.

“The era of dirty coal is clearly over,” Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis said Monday at the the United Nations conference in Madrid, where some 15,000 diplomats and environmentalists will discuss the threats posed by climate change. “Greece can be a paradigm of how energy transition and climate action can create green jobs and sustainable growth.”

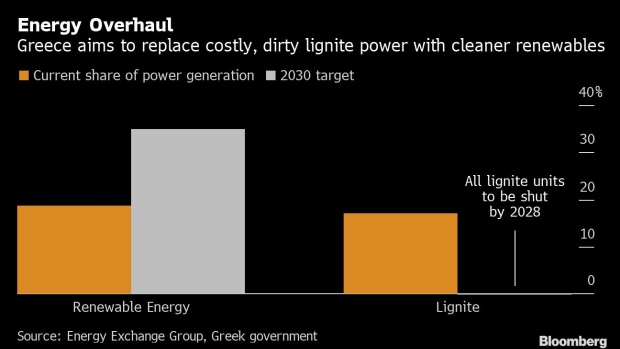

The newly elected leader has vowed to close all 14 of Greece’s lignite-fueled power units by 2028. These plants account for over a fifth of the country’s electricity capacity, and are critical to local economies.

If Greece hopes to replace the majority of its lignite assets with renewables -- which the new 2030 targets suggest it’s aiming for -- it will need to mobilize major volumes of investment. There has been just 3.3 billion euros invested in clean energy projects since 2015, compared with 9 billion euros in the previous five years, according to research from BloombergNEF.

What Our Analysts Say:

“Gas and renewables are already vying for the 5-gigawatt gap that the coal closures will create. The government seems very clear on its commitment to phase out most lignite by the early 2020s.”

--Katherine Poseidon, BloombergNEF analyst

In Megalopolis -- site of a 20,000-seat ancient amphitheater -- locals worry that plans to close a plant by June will accelerate the city’s decline and complain that there’s not a clear plan for the fallout. Proposals range from using available land to grow cannabis to providing incentives for workers to relocate.

“Megalopolis has given its blood for the energy of the country,” said Yiorgos Saflagioras, a 41-year-old mine worker. “They should respect us in the new age.”

Signs of decay are already evident in the city. Around 60% of the shops have closed, and one of the four primary schools is shutting because of a lack of students.

For Western Macedonia in Greece’s north, which faces the shut down of two facilities next year, the fallout could be even more extreme. The remote, landlocked region lacks the infrastructure and resources to help attract fresh investment, according to Georgia Zebiliadou, a regional official.

“It’s clear that if there’s a violent end of lignite, our region will face a catastrophic Armageddon,” said Zebiliadou.

While lignite’s days are numbered, the new era is struggling to take shape. Greece’s new government aims to nearly double the share of renewable energy to 35% by 2030, higher than a previous target of 31%.

To get there, the government is relying on PPC and its ability to partner with foreign investors. But for that to happen, the company -- which lost 353 million euros in the first nine months of this year -- needs to be stabilized.

In November, the European Commission warned that utility still needs “to tackle the longer-term challenges of arrears and strategic defaulters” on its books, as well as reduce its lignite exposure.

PPC’s importance radiates well beyond the energy sector. In addition to accounting for more than half of the country’s power supplies, the utility had 3.9 billion euros in net debt at the end of September, and more than a third of its debt obligations were held by Greek banks.

“If PPC falls, the banks will fall, the national economy will fall,” Energy Minister Kostas Hatzidakis told lawmakers last week during a debate on a new energy law. The legislation, which was approved on Nov. 27, includes measures for modernizing PPC including employee buyout programs to reduce costs and to support the plan to wind down lignite.

For communities that will pay the price for the shift, the government plans to spend 130 million euros to help with the transition. The state will provide tax and investment incentives and help with retraining displaced workers. But with uncertainty looming over hundreds of families in Megalopolis, the feeling is it’s too little, too late.

“I am worried about my parents as my father is a PPC employee,” Aggeliki Tsidoni, a 19-year-old student from Megalopolis. “Moving from the plant to another type of employment will take time. I don’t know yet whether I’ll return when I finish my studies” in Athens.

--With assistance from Katherine Poseidon and Vassilis Karamanis.

To contact the reporters on this story: Paul Tugwell in Athens at ptugwell1@bloomberg.net;Sotiris Nikas in Athens at snikas@bloomberg.net;Eleni Chrepa in Athens at echrepa@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Chad Thomas at cthomas16@bloomberg.net, Chris Reiter

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.