Dec 16, 2018

Green Groups Are Set to Crash Into Global Populists Over Pollution Cuts

, Bloomberg News

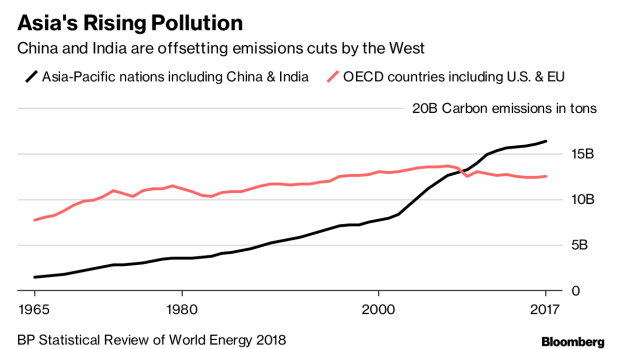

(Bloomberg) -- The global environmental movement set itself on a collision course with populists from Australia to France and the U.S. over an agenda of ever-tightening curbs on pollution.

Fresh from endorsing rules to implement the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change, diplomats, along with pressure groups and United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, are shifting toward persuading governments to back deeper cuts in fossil fuel emissions.

The effort, which will culminate at a UN leaders summit in September, is aimed at reining in greenhouse gases. While scientists say that’s necessary to stave off more of the kind of violent weather that caused a record $140 billion in damage in 2018, a growing backlash to those restrictions is emerging worldwide. It’s taken the form of Yellow Jacket protests in France, the Australian government being ousted, and U.S. President Donald Trump’s support for coal mining. Green groups are digging in for a fight, backed by like-minded businesses and nations.

“Part of what’s building is using the momentum in the real world to put pressure on policy makers to go further and faster,” said Jake Schmidt, who follows climate policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington. “Conditions on the ground have changed, and countries should reflect that by changing targets.”

After two weeks of talks in Katowice, Poland, envoys from almost 200 countries this weekend adopted a set of rules guiding the 2015 Paris deal, where all countries rich and poor alike pledged to voluntary limits on their emissions. The measures include standards for measuring, reporting and verifying carbon. Having those in place allows green groups to pivot to their broader agenda of reining in the use of oil, natural gas and coal.

Rising carbon concentrations in the air have driven up the global temperature about 1 degree Celsius since the start of the Industrial Revolution, with scientists suggesting that current plans leave the planet on track to warm 3 degrees or more by the end of the century. That would mark the quickest shift in the climate since the end of the last ice age 10,000 years ago.

Using a word that’s UN jargon for deeper emissions cuts, Guterres vowed to wring stronger promises from world leaders who’ll attend a summit he’s organizing in New York on Sept. 23.

“Ambition will be at the center for the climate summit,” the secretary general said in a statement after the discussions in Poland wrapped up. “Science has clearly shown we need enhanced ambition to defeat climate change.”

The September summit will start a week of events designed to spur action on the environment. The announcements there will feed into the next round of climate talks, to take place in Chile, where the diplomats want to start into a process of reviewing national targets and finding ways to make them tighter. That so-called “ratchet mechanism” was one of the key tools approved in the Paris deal.

“We can give a signal to the world that this is something that is taken seriously,” said Ola Elvestuen, Norway’s climate minister. “Everyone needs to do what they can.”

Several factors emboldened them to demand quicker action:

- A swift plunge in the cost of wind and solar power has made renewables more competitive with traditional forms of energy, especially coal, which pollutes the most.

- More extreme weather events this year, from wildfires in California to more powerful hurricanes and a drought in Germany, focused attention on the climate.

- An alliance of small island states and poor nations most vulnerable to climate change is demanding industrial nations make good on a pledge to disperse $100 billion a year in climate aid by 2020.

“You can have much greater level of ambition than you committed to for the same cost as they took into consideration when they agreed on Paris,” said Alden Meyer, who’s been following the UN climate talks for more than two decades at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington. “Everyone should go back and sharpen their pencils and see how these dramatic reductions in costs can impact what they can do.”

Yet a number of skirmishes against environmental rules in the past year indicate that even the greenest of governments has limited room for maneuver.

- In France, a grassroots movement blocked roads and rioted in Paris for weeks ahead of the climate talks, forcing President Emmanuel Macron to scrap higher taxes on fuel.

- German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government is weighing a program that would slow the pace of closing coal power plants after union leaders and industrial companies objected to rising energy costs.

- Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison took office in August after infighting over pollution cuts forced out Malcolm Turnbull. The new leader scrapped plans to write those limits into law.

- Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s effort to tax carbon has run into opposition from provinces. It’s likely to be a key issue in the general election next year.

- Brazil’s President-Elect Jair Bolsonaro has vowed to roll back environmental restrictions when he takes office. The government already abandoned plans to host next year’s climate talks, citing the transition.

Those episodes suggest Trump isn’t alone in his reluctance to embrace the pollution limits that come with the Paris accord. While his government participated in the talks in Katowice and has boasted about the scale of emissions reductions the U.S. is making, Trump has vowed to pull out of the Paris deal and is seeking to encourage the use of coal.

“Alarmism should not silence realism,” P. Wells Griffith III, principal deputy assistant secretary for the Office of International Affairs at the U.S. Department of Energy, said at a White House-sponsored event at the talks in Katowice. He added that U.S. policy “is not to ‘keep it in the ground.’ It is to use it in a way that’s clean and efficient.”

Even so, even businesses are starting to push for stricter rules, anticipating that certainty about where policy is headed will help them profit.

“Companies are positioning their businesses for success in a low carbon economy,” said Karl Vella, manager for climate policy at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, which represents 200 firms from Apple Inc. to Ikea and State Grid Corp. of China. “Any lack of ambition on the pace of policy making will create uncertainty and slower investment.”

It’s the island nations fearful they’ll be inundated by rising sea levels whose voices are heard the loudest at the UN talks, and they’re demanding urgent action.

“We face season after season of force-four hurricanes, rising sea levels and impacts on our coastal communities,” said Simon Stiell, environment minister for the Caribbean nation of Grenada. “We have to learn to adapt, but we have limited means.”

To contact the author of this story: Jeremy Hodges in London at jhodges17@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Reed Landberg at landberg@bloomberg.net, Ros Krasny

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.