Apr 21, 2019

Have a Credit Card? You’re Among China’s Fortunate

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Owning a credit card can seem like a rite of passage in the U.S., where even a college student with no income can sign up and start swiping. More than two-thirds of Americans over the age of 15 carry plastic.

In China, however, just 21 percent do. That’s not because they don’t want to shop: In a recent survey of 3,100 internet users, UBS Group AG found that that 44 percent plan to consume more, spending on items such as smartphones and air conditioners, while only a third intend to scale back. Nor are they financially irresponsible. Most attempt to borrow within their means, with the average loan expected over the next year amounting to little more than one month’s salary.

The fact that most of them nevertheless won’t be able to charge their purchases is more than an inconvenience; this lack of access to credit dramatically undercuts their financial security. China’s haves and have-nots are divided by a thin piece of plastic.

Cardholders are a privileged bunch. An average borrower is a 34-year-old millennial who earns at least 110,000 yuan ($16,400) a year, close to three times the average urban income in China. There’s an 82 percent chance she lives in one of the country’s four biggest and wealthiest megacities: Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

For everyone else, there’s online borrowing. Loans come easy to those who’ve established good Sesame Credit, the scoring system developed by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. for shoppers on its e-commerce platforms. Those who haven’t, or who want to borrow even more, resort to peer-to-peer lending or even payday loans.

Online rates are much higher that those charged by credit cards, and China has seen a stream of predatory lending scandals in recent years. U.S.-listed Qudian Inc., for instance, sparked public fury in 2017 after disclosing that more than half of its transactions the previous year had annualized rates exceeding the legal limit of 36 percent. In March, state-owned CCTV ran a lengthy interview with a woman whose debt ballooned 70-fold in three months because she took out a “714 missile loan,” so-called because they are typically due in seven or 14 days. This problem would have been far less severe if she’d had a credit card, which charges no interest for a month.

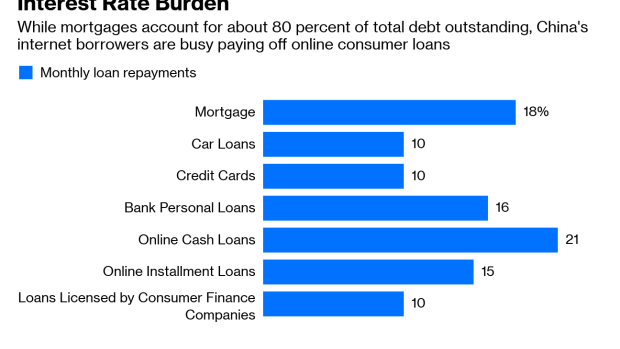

The burden of higher rates is weighing on borrowers. While mortgages account for 80 percent of the total outstanding debt for respondents in the UBS survey, such payments represent only a small part of monthly outlays.

This begs the question why banks aren’t doing more to help people get credit cards. Lenders can earn about 14.5 percent effective yield from such clients, whose 1 percent delinquency rate makes them prime borrowers. What’s more, the People’s Bank of China now allows commercial banks to package their credit-card loans into asset-backed securities that they’ll have no trouble selling. The typical yield for the safest tranche, which is practically risk-free, ranges from 3 percent to 5 percent, a handsome return.

While banks tend to balk at risky, unknown borrowers, it’s not all that difficult to assess creditworthiness these days. If a customer has a checking account with Bank of China Ltd., for instance, the lender not only has access to her income slip, but also how much she spends every month. Online lenders, on the other hand, have to work off very limited — and speculative — information such as social credit scores, or the social graph.

Beijing bureaucrats believe millennials love “cashing” out their credit cards to buy penny stocks, or taking out home-improvement loans to speculate on the real-estate market. (How severe these practices are is anyone’s guess.) With the rise of fintech, though, young borrowers can always find funding somewhere. Preventing them from getting credit cards only creates new problems without addressing that fact.

China likes to say it wants its economic growth to be driven by domestic consumption rather than industrial production or exports. So let the young consume — trust them with a credit card to buy that $1,000 iPhone, or these days, Huawei Technologies Co.’s P30 Pro. Even your big state banks will benefit.

To contact the author of this story: Shuli Ren at sren38@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.