Dec 15, 2020

Hedge-Fund Boss Ignites Swedish Race Debate With Bias Complaint

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Swedish social media lit up last month when a well known Black hedge-fund manager vented about discrimination, questioning the country’s prized egalitarian credentials.

Sean George, 48, who grew up in the Caribbean before moving to Sweden at the age of 12, broke a two-year long silence on why he was forced to go solo with his fund in Stockholm in 2018. After decades of working overseas at firms like UBS Group AG, Bank of America Corp. and Deutsche Bank AG, he said he failed to get as much as an interview when he moved back to Stockholm.

“I never felt creed, color, social background were issues when working in the U.S. or the U.K,” George said in an interview, after his post prompted debate on diversity in the country. “Here, it certainly seems to be in the air.”

As the Black Lives Matter movement shines a light on race-related issues globally, the picture George paints of discrimination in Sweden has sparked some soul searching in a country that sees itself as a bastion of equality. Sweden has stood out for its generous immigration policies, and ranks high on income and gender equality.

Yet George has a very different tale to tell. A Swedish resident, he returned to the country four years ago to be closer to his daughter after an international career he had embarked on in 1996. His experience in senior positions at top-notch financial institutions opened no doors for him in Stockholm.

He describes the financial community in the biggest Nordic city as a closed network of insiders. He founded his own firm and is now the chief investment officer of his $100 million Hamiltonian Global Credit Opportunities fund -- shortlisted in the 2020 HFM EuroHedge Emerging Manager Awards.

Others make similar observations. Eva Olsson, who worked as a senior sell-side analyst for 18 years at international firms including Deutsche Bank and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc., says the country’s financial markets are “difficult to enter.”

“That’s one of the key reasons I never tried to have a career in Sweden, but went to Hong Kong and then on to London,” she said.

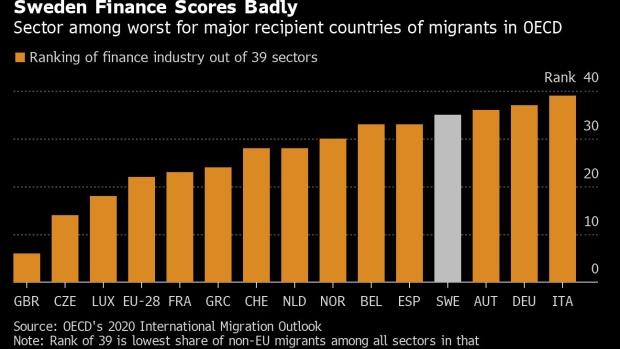

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggests the inclusion record of Sweden’s financial industry isn’t pretty. Thomas Liebig, a migration specialist at the body, points to a recent OECD study that puts the country close to the bottom of the OECD’s overall ranking.

Within Sweden’s banking sector -- one of the country’s biggest employers -- some are beginning to acknowledge that the industry has an issue.

“Some say that Sweden is the most equal country in world, but I don’t think that’s true,” said Maria Hamstedt, the chief inclusion and diversity officer at SEB AB, among the nation’s biggest lenders. “Things look very nice on the surface but once you start to dig, you can see we have many of the same challenges that other countries have.”

A key part of the problem is that Sweden -- like Germany and France -- doesn’t compile statistics on race. That prevents all debate on race in a country where just over a third of the population claims some kind of foreign or migrant background, according to research by Karlstad University.

Asa Lindhagen, Sweden’s minister of gender equality with responsibility for anti-discrimination, has commissioned reports on how cities tackle race issues in the workplace. The first of them is due in March.

“Sweden is characterized by a culture where we don’t see skin color” out of racial sensitivity, said Katarina de Verdier, who’s working on the report for Stockholm. That makes tracking inclusion and discrimination difficult, if not impossible.

Top Swedish lenders acknowledge there’s a need to create a more diverse and inclusive culture. Swedbank AB, for example, has started an internship program for foreign-born students.

Still, with debate on race “almost non-existent,” it’s hard to have “a policy like Goldman Sachs on recruiting Black people,” said SEB’s Hamstedt.

Asa Nilsson Billme, head of diversity and inclusion at Nordea Bank Abp in Sweden, said since it’s “illegal” to track people by ethnicity of skin color, setting targets is impossible.

Not surprisingly, people of color or with foreign backgrounds are steering clear. Alexis Cousins-Culver left Barclays Plc in Sweden, saying she couldn’t fit in. The sector is “exponentially more closed-off and elite” than in New York or London, she said. When she agreed to relocate to Sweden for the bank, she “underestimated how excluded I would feel as the only woman of color without any prior Nordic education or background.”

She now works at the Stockholm School of Economics, turning to research to help better the industry from outside. But the problem is, “if you can’t track it, you can’t measure progress,” she said.

The financial industry’s “clubby environment” will eventually change, said Bo Becker, the Cevian Capital Professor of Finance at Stockholm’s School of Economics. “The industry will modernize and become more open.”

That change can’t come soon enough for George.“The issues I experienced in 1996 are going on now, and if things don’t change it will happen to my daughter,” he said. “Yes, I am taking a risk by speaking out, but I am fighting for her.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.