Oct 7, 2020

Hedge funds fall flat when it comes to diversifying their ranks

, Bloomberg News

The place might sound like a Wall Street throwback: Men do the trading. Women do the marketing. Not a single investment employee is Black. But here’s something even more remarkable: none of this is so remarkable at all.

This, after all, is the hedge fund industry, one of the most White-male-dominated businesses in the mostly White-male world of American finance.

Like most hedge-fund firms, this one, Solus Alternative Asset Management of New York, declined to discuss its roughly 50-person workforce, or how and why it hires who it does. In fact, hard numbers are difficult to come by all across this hush-hush business -- which tends to be how hedge funds like it.

But what data are publicly available, as well as interviews with people in the business, all point to the same conclusion: the US$3.2 trillion hedge-fund industry is even more segregated by race and gender than other corners of U.S. finance.

Intensely private, free of public stockholders and typically shielded by strict work contracts, many firms are able to operate much like the Wall Street partnerships of old. Many women and people of color say the effect, intentional or not, is a system that often favors white men and perpetuates the divides in the industry. This week, one of the industry’s most senior females settled a pay dispute with her previous employer, a case she said was about gender discrimination.

The numbers tell the story: not one of the nation’s 30 largest hedge funds is run by a woman or a person of color. Most women- or Black-owned firms have less than US$500 million in assets under management. Many have far less.

Firms including Citadel, Renaissance Technologies, DE Shaw & Co., Two Sigma Investments and Millennium Management declined to discuss or give data about the diversity of their investment teams. Industry insiders say while these giant firms may have diversity efforts, the percentage of women and African Americans in investing roles is still low. And that under-representation is even more acute at smaller firms, which have fewer staff and are more likely to recruit from tight-knit social circles.

Well-known shops such as Tiger Global Management, Light Street Capital Management and PointState Capital have very few or no women or Black people helping to manage money. The entire leadership team listed on the website of Aristeia Capital, which was founded in 1997, is made up of white men. Over at Sculptor Capital Management Inc., just six out of its 45 U.S. managing directors are women and they’re all in non-investing roles. Only one is African American.All the firms declined to comment.

“The hedge fund industry is going to be one of the toughest to crack,” said Troy Dixon, founder of one of the few sizable Black-run hedge funds, Hollis Park Partners.

Why is diversity such a problem for hedge funds?

The reasons are many, industry veterans say. One is a Wall Street culture that hires from within and rarely hands coveted trading roles -- the people who move the money -- to minorities or women, cutting off a key avenue for getting ahead. Another is that there are few plum investment jobs, and little turnover at the best firms. And third, it may come down to the fact that hedge funds themselves are resistant to change, and no one is forcing it on them.

It’s a system that works against those on the outside. Without experience at a hedge fund or working under the tutelage of one of the industry’s big names, minorities don’t gain the credibility and contacts needed to launch their own shops or attract sizable assets.

Women- and minority-owned hedge funds controlled less than 1% of total industry assets in mid-2017, according to a report by Harvard Business School professor Josh Lerner.

“Look at who the big players are: do they look very diverse by any metric?” said Barbara Ann Bernard, founder and chief investment officer of Wincrest Capital. “You need scale to get ahead in this industry.”

Talent Pool

One common refrain from the industry is that the pool of incoming talent is too limited for hedge funds to rapidly increase their diversity. But those who’ve worked on the problem for decades say firms aren’t always using resources available to them.

“The notion that there’s not enough talent, to me, is very insulting,” said Sue Toigo, co-founder of the Robert Toigo Foundation, a non-profit that works on the placement and advancement of minority MBA holders in the finance industry.

“It simply means people are lazy,” she said. “They haven’t taken the time to look for it.”

Toigo said that hedge fund investors could add pressure by seeking out diverse leadership teams, for example.

That view was echoed by Robert L. Greene, chief executive of the National Association of Investment Companies, a network of more than 100 minority-owned hedge funds and private equity firms representing over US$175 billion in assets under management.

“Diversity doesn’t just happen,” he said. “Society is naturally diverse, but selection isn’t. You need to show intention.”

Some on the client side have started to take action. Cambridge Associates is seeking to double its investments in minority managers, adding US$20 billion in allocations.

A few hedge funds have changed the make-up of their senior ranks. When Stephen Mandel stepped back from his Lone Pine Capital, for example, he left the portfolio in the hands of a three-person team, two of whom are women, including one of South Asian origin.

While most firms declined to share data, two of the industry’s biggest, Point72 Asset Management and Bridgewater Associates, did provide figures.

About 40 per cent of U.S. staff at Point72 and their training Academy were diverse in 2019 -- that includes investing and non-investing roles of women, and people of color, including the industry’s better-represented Asian and South Asian populations.

“Our ability to succeed is dependent on employing people who see things other people miss and recognize developments other people do not,” spokeswoman Tiffany Galvin-Cohen said in an email.

At Bridgewater, about one in four investing roles is held by a minority, and nearly one in five is a woman. The firm is “looking to build on our existing diversity and inclusion efforts, and expand them where relevant,” spokeswoman Ryan FitzGibbon said.

On Monday, Bloomberg reported that Bridgewater reached a settlement with former co-Chief Executive Officer Eileen Murray over her exit package. The two sides had been negotiating for months, a fight that dragged on because the firm’s offer was less than what has been paid to men who left the company and below the status of her position, according to one of Murray’s advisers.

Sexist Challenge

In an industry that’s so dominated by white men, women face a very specific bias, said Svetlana Lee, who ran Varna Capital.

“Everyone worries about what happens when a woman has children,” said Lee. While her former bosses, who include industry titans Richard Perry, Seth Klarman and David Einhorn, were supportive mentors, she said there is an industry-wide problem: some recruiters view women as “an open risk factor.”

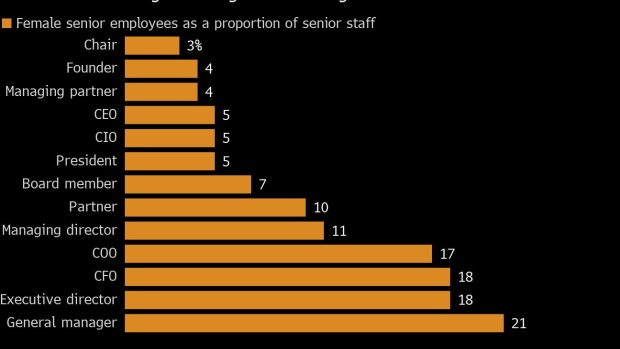

Fewer than one in five employees at hedge funds globally are female, according to research firm Preqin.

Rashad Robinson, president of racial justice organization Color of Change, said that for the hedge fund world to make real progress firms should consider linking financial incentives to hiring and retaining a diverse workforce.

“When money comes into play, people get creative,” he said.