Sep 20, 2019

As misinformation spreads, here’s how Canadian voters can stay vigilant

, BNN Bloomberg

The dangers of 'deepfake' videos during an election period

With the federal election campaign now in full swing, voters may have encountered a news story or two that seems untrue, a photo that looks fake, or video that seems completely fabricated.

But sometimes it’s hard to know for sure.

The sharing of incorrect or misleading information without knowing if it’s false – or misinformed – has been happening for a long time, notes Fenwick McKelvey, an associate communications professor at Concordia University who studies the topic.

“There’s always been a lot of misinformation spreading and I think the one thing that we are trying to attend to more is the rise of disinformation, intentionally misleading information,” he said in a phone interview.

“Deepfakes” and “dumbfakes”, which refer to video or audio fabricated using artificial intelligence to make it seem like a person said something they didn’t, are examples of disinformation.

“These are relatively new things that are happening,” Dianne Lalonde, a PhD candidate in political science at Western University, told BNN Bloomberg in a television interview earlier this week.

“With sci-fi videos, of course we know that there’s some editing going on. But with politics, we think that usually if it’s on the news, or it’s being shared, it’s a real video. And deepfakes and dumbfakes really challenge this.”

A famous example of a dumbfake is the video created by actor Jordan Peele last year which used AI to make it appear that former U.S. president Barack Obama delivered a public service announcement about false news. In May, a slowed down video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that made her appear impaired garnered millions of views on Facebook.

Meanwhile, in Canada, media personality Rick Mercer called out the Conservative candidate in the Burnaby North—Seymour riding earlier this week for sharing a false endorsement on social media.

The spread of false information become so prevalent, especially during election campaigns, that social media companies have dedicated entire teams to detecting and removing content that promotes it.

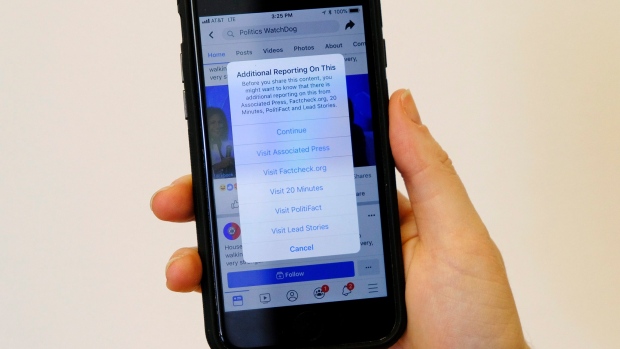

A spokeswoman from Facebook Canada told BNN Bloomberg by phone there’s tools available on the platform to help users identify and report content they think could be misleading or false. The company uses automated process as well as third-party fact checking teams for more complicated content to determine if items needs to be removed for breaking Canadian law or violating Facebook’s community standards.

Twitter also has its own strategy for detecting and removing malicious information.

Back in April, Canada’s national cybersecurity agency warned of the potential effect social media influence could have on the federal election including the “burying legitimate information,” “polarizing social discourse,” and “calling into question the legitimacy of the election process,” but noted meddling is unlikely to be on the same scale as the suspected Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft News, a non-profit organization that dedicates itself to tackling challenges around misinformation, warns older people tend to be more vulnerable as they're more trusting of the information they see online.

“It's actually not fake content that people should be worried about, the real concern is genuine but misleading content,” she said in an email.

“During elections, we often see genuine but old videos circulating as if they are new, photographs used out of context, or misleading headlines or captions.”

She adds the most effective disinformation has kernel of truth to it, so voters should watch for sensational, highly emotive content designed to create fear or drive down trust in democratic institutions.

While some content containing misinformation is easier to spot than others, McKelvey says there are some tricks voters can use to stay vigilant.

“Always be looking out for stories [that are] too good to be true, if they’re exactly what you expect, and if they’re potentially playing to your beliefs,” he said.

“Look at the source. How do they make their money? Where are they potentially making their content?”

Wardle adds one of the most powerful tools to spot false information is through a reverse image search to determine where the content originates.

“If you see an account you're not sure about do a reverse image search on the profile picture,” she said. “If it´s a video, do a screenshot of the video and run a reverse image search on that.”

The onus to identify and stop the spread of false information is on a number of actors including policymakers, journalists, educations, and social media companies, Wardle says, adding the biggest challenge the social platforms have is scale.

“The amount of content uploaded every second is eye-watering. Neither humans or machines can adequately monitor all of this content in real time,” she said.

“But ultimately, we as users need to take responsibility for what we share.”