May 25, 2018

Here's What Turkey in Crisis Can Learn From Other Central Banks

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may have finally conceded to his financial lieutenants’ currency-rescue plan, but a look back across recent eleventh-hour rate hikes in emerging markets shows he’s at the start of a long and thorny path.

And that’s only if he chooses to do things by the book. Russian Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina has been rewarded with inflows and low volatility for her ultra-orthodox monetary policies, but it has taken three years to get to that stage. Argentina is already benefiting from its extreme hike this month, a move more than double the 300 basis points Turkey raised rates by on Wednesday.

Ideally, Erdogan should be taking his cue from the same place that Nabiullina learned her tricks: Turkey’s own central bank. Back in early 2014, the country’s policy makers defied political pressure and bumped up rates in an emergency meeting, setting an example for the rest of the emerging world. But given that Erdogan now calls interest rate hikes as “the mother of all evil,” it seems unlikely he will look to the past for guidance.

“History repeats itself,” said Julian Rimmer, a London-based trader at Investec Bank Plc. “The first time as tragedy, then as farce.”

Here are some of the recent examples from emerging markets:

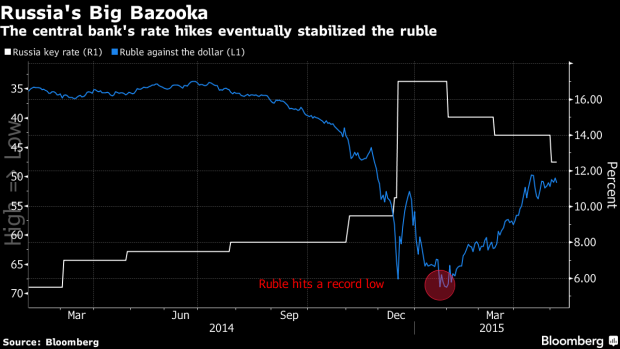

Russia

As plunging oil prices combined with sanctions to send the ruble into a tailspin in December 2014, central bank chief Nabiullina called a late-night emergency meeting and jacked the key rate up to 17 percent. After an initial rebound, the ruble continued its slide into 2015 before making a gradual recovery.

Since then, the policy has been to keep borrowing costs elevated and allow the ruble to trade freely, an approach that has helped the currency outperform peers in recent years. The stance led Morgan Stanley to dub the Russian central bank developing Europe’s “most orthodox.”

The one big difference with Turkey? The central bank was left alone by politicians even as the Kremlin’s relations with the U.S. deteriorated.

Argentina

When it comes to shock and awe, Argentina’s policy makers’ recent barrage of rate hikes make Turkey’s move look rather demure.

Their response -- three increases in a single week that took the key rate up 675 basis points to 40 percent -- set a high watermark among major economies. They also started talks for a $30 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund. That, at last, buttressed the peso, which has lost about a quarter of its value this year, the most among peers, although the lira is now a close contender.

Win Thin, the New York-based head of emerging-markets strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman & Co, was reassured: “Rate hikes don’t always work. They have a better chance of working if there is a comprehensive plan, like Argentina.”

Ukraine

The ex-Soviet republic once laid claim to the highest key rate globally. Policy makers in Kiev didn’t drag their feet with a series of rate hikes in February and March 2015 aimed at arresting a plunge in the hryvnia after its peg was abandoned as a condition for negotiating an IMF bailout. The nation’s war with Russian-backed separatists had hobbled the economy and ultimately drove the government into default.

The measure, taken alongside currency controls, stemmed the hryvnia’s slide and bought Ukraine time to restructure its dollar debt. Since then, currency controls have been gradually lifted and the interest rate reduced to 17 percent, which is still (just) the highest rate in Europe. But the hryvnia never recovered its former value.

Turkey

It’s becoming harder and harder to imagine, but back in 2014 Turkey’s own approach to monetary policy was the model other central banks were using at times of crisis. In January of that year, Turkey’s central bank raised all its main interest rates at an emergency late-night meeting in an effort to shore up the lira amid domestic upheaval and a global emerging-market rout. The currency recovered after the move that went against government pressure and reversed years of policy aimed at stoking growth.

--With assistance from Marton Eder, Paul Abelsky and Selcuk Gokoluk.

To contact the reporters on this story: Natasha Doff in Moscow at ndoff@bloomberg.net;Alex Nicholson in Moscow at anicholson6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Samuel Potter at spotter33@bloomberg.net, Cecile Gutscher, Jeremy Herron

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.