Aug 28, 2019

Here's where capital flight from Hong Kong will show up first

, Bloomberg News

Would Hong Kong’s Turmoil Spur Capital Outflows?

It’s one of the biggest questions hanging over Hong Kong as anti-government protests head into a 13th week: Will investors pull their money out?

So far, there are few signs of a mass exodus. But the risk of capital outflows is undoubtedly rising as Hong Kong’s summer of unrest pushes the economy toward a recession, weighs on asset prices and fuels doubt about the city’s future as a financial hub.

The stakes are high for Hong Kong, which is one of the world’s most open economies, with bank assets equal to about 8.5 times of its GDP and offshore traders accounting for about 40 per cent of volume on the city’s stock market. That means a significant withdrawal of deposits and investors would land a heavy blow to its economy and markets.

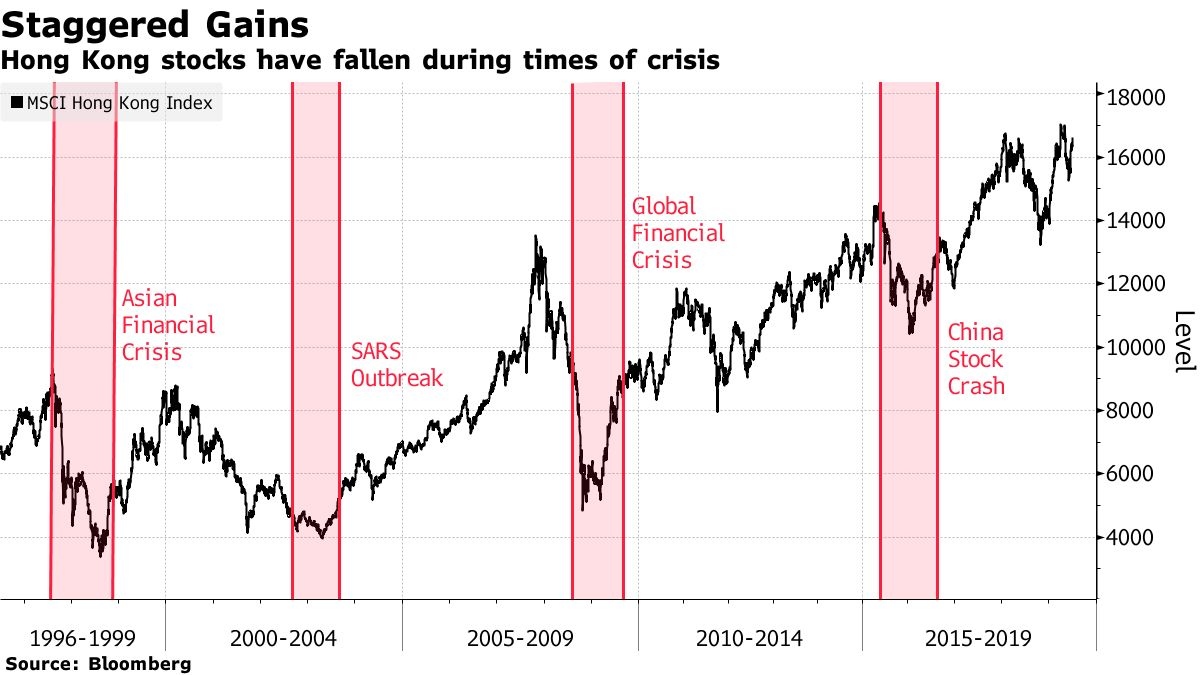

While the city has periodically experienced sustained bouts of outflows -- notably during the global financial crisis and the SARS epidemic -- there’s no single indicator that shows how money is moving in and out of the territory. The trends in those periods were evident in stock market and real estate slumps, along with a variety of metrics that, taken together, help tell the whole story.

Here’s what they’re showing today:

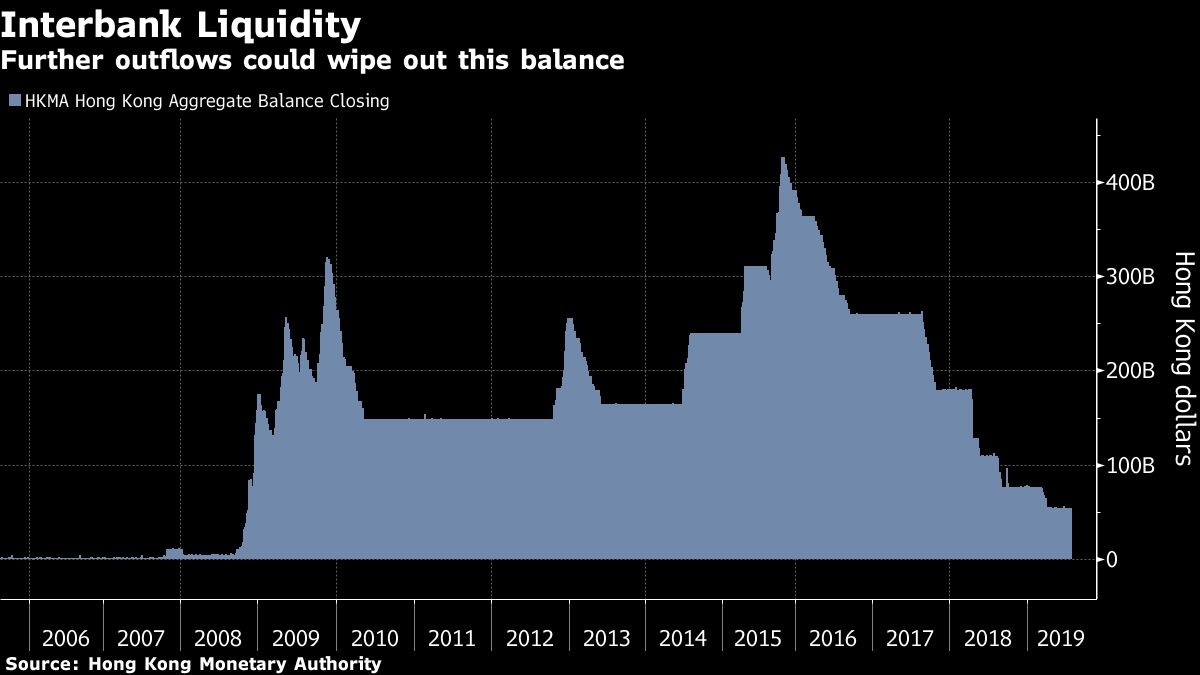

Aggregate Balance

Changes in the aggregate balance of interbank liquidity -- bank funds held with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority -- are among the most visible indicators of fund-flow pressures. The balance recently dropped to HK$54 billion (US$6.9 billion) from about HK$180 billion after HKMA used funds to defend the currency peg -- a move that Kevin Lai, chief economist for Asia excluding Japan at Daiwa Capital Markets Ltd., said may have had more to do with the period when the U.S. Federal Reserve was raising interest rates.

Foreign Currency Assets

Changes in the level of foreign currency assets held by Hong Kong’s banks are another proxy for capital flows. The city has already seen a decline of more than US$45 billion since mid-2017 as the Fed tightened monetary policy, according to Daiwa’s Lai. He estimates Hong Kong has a buffer of nearly US$140 billion before it runs into a liquidity crisis that would trigger a surge in banks’ borrowing costs.

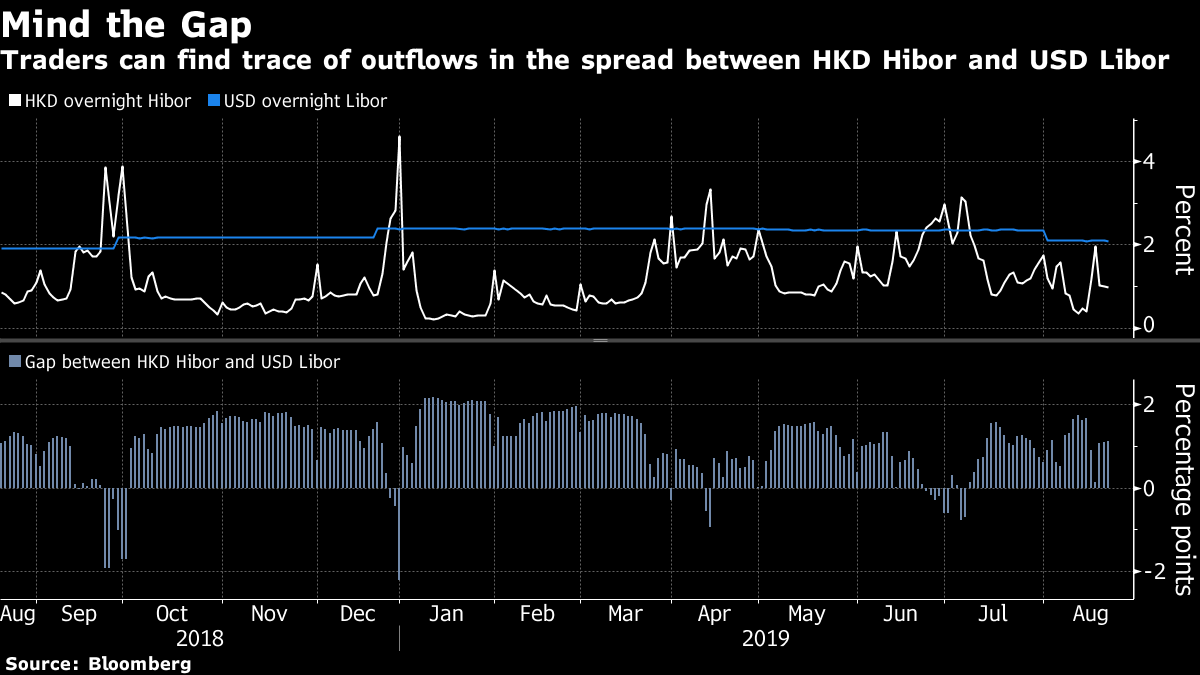

Interbank Rates

Another closely watched measure is the local lending rate between Hong Kong’s banks, known as Hibor. If it’s higher than borrowing costs in U.S. dollars for a sustained period (say, more than a month) that would hint at outflows, said Tommy Ong, managing director for treasury and markets at DBS Hong Kong Ltd. As money exits the financial system, liquidity gets tighter and interest rates rise.

Hong Kong dollar interest rates have mostly been lower than U.S. borrowing costs, though they were briefly higher in late June and early July due to seasonal factors.

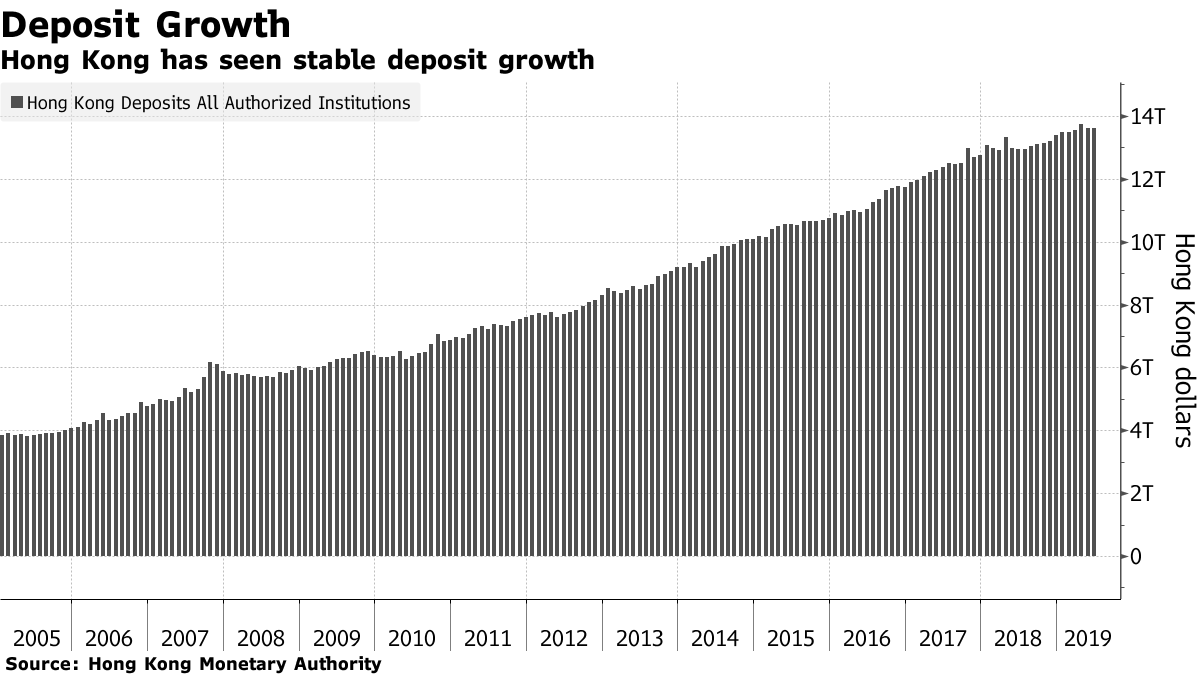

Deposits

A meaningful decrease in Hong Kong dollar deposits would suggest investors are switching their local assets into other currencies. Bank customers in Hong Kong held HK$13.6 trillion in deposits as of June, HKMA data show, a slight decrease from earlier in the year but still near a record high.

“The risk is contained at the moment,” said Carie Li, an economist at OCBC Wing Hang Bank Ltd. in Hong Kong. “But ongoing protests, the yuan and the trade war are causing concern.”

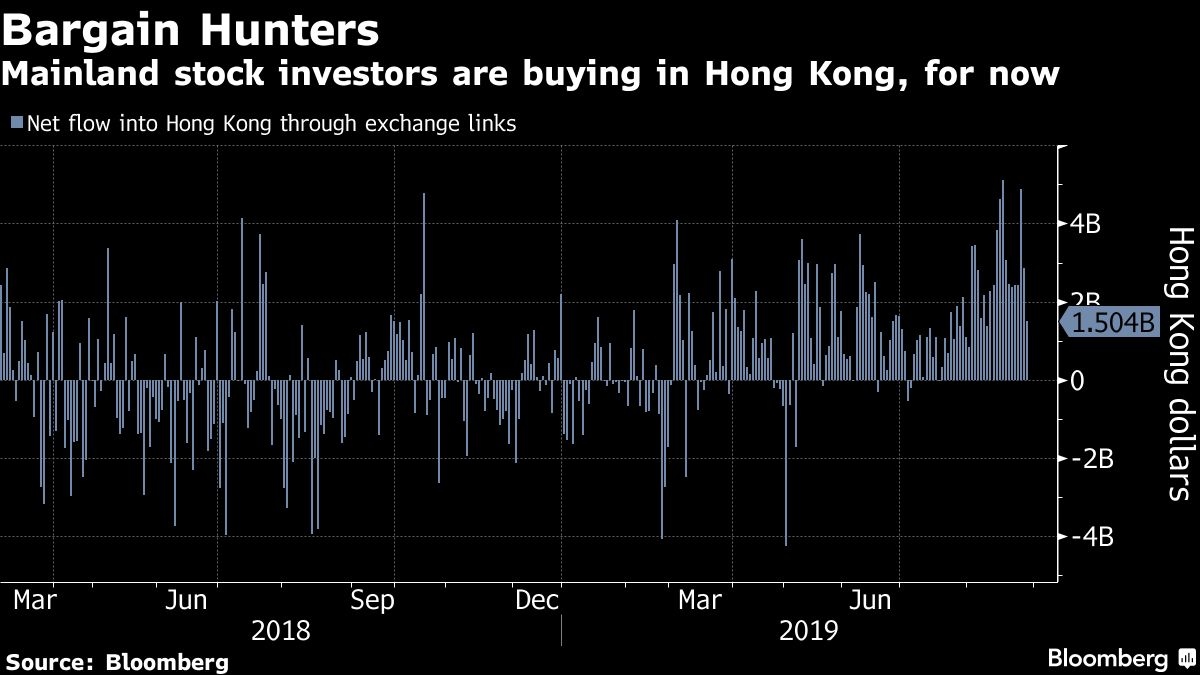

Stock Links

Hong Kong’s stock-exchange links with mainland China provide a daily look at cross-border capital flows. For now, mainland investors are hunting for bargains as Hong Kong stocks fall: They added a net US$8.4 billion to their holdings in the 28 trading sessions through Tuesday.

Hong Kong Dollar

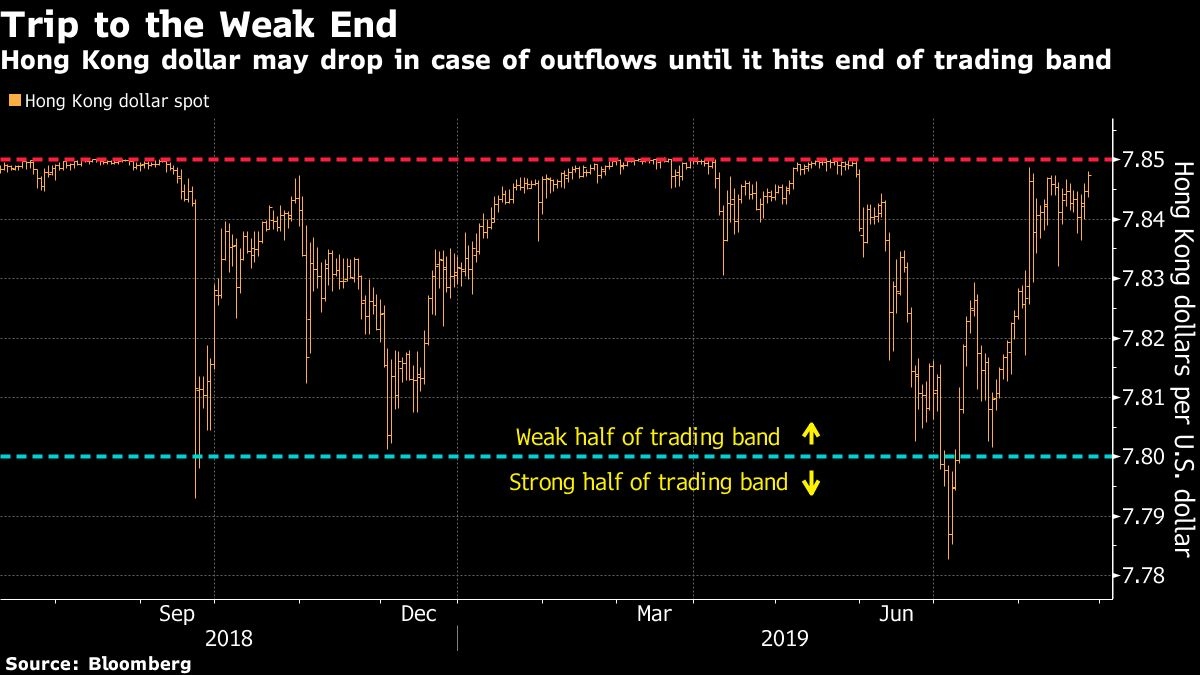

For many economies, a falling currency can be a sign of investors heading for the exits -- think of the British pound’s decline amid Brexit uncertainties. Weakness in the Hong Kong dollar can also reflect capital outflows, but the currency’s usefulness as an indicator is limited because it has been pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1983.

The city’s de-facto central bank says it’s committed to keeping the currency in a tight trading range between HK$7.75 to HK$7.85 against the greenback. If the rate neared the bottom end, expectations of HKMA intervention would likely lead to a spike in borrowing costs, a move that would force traders to quit their short positions and trigger a spike in the exchange rate.

Share Prices

Hong Kong has the world’s fourth-biggest stock market by value, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Share prices in the city have dipped during previous crises as investors have fled, though the city’s bourse was a fraction of its current size.

Though the data don’t show signs of significant outflows, Hong Kong’s political and business leaders have warned of lasting economic damage to the city. That could also mean fleeing money, according to economists at Natixis SA.

“If the negative sentiment continues, the rapidly decelerating economic environment could entice capital outflows,” they wrote in a note published Wednesday.

--With assistance from Matt Turner, Amanda Wang and Kana Nishizawa