Jan 4, 2021

Higher Food Costs Stalk Britons as New Year Brings Brexit

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The supermarket sticker shock threatened by a no-deal Brexit has been averted, but British shoppers still may find prices creeping higher in the new year.

A raft of red tape plus new checks at the border could add 3 billion pounds ($4.1 billion) in costs for food importers, according to the U.K.’s Food and Drink Federation. That’s about an 8% increase -- some of which could work its way down to prices paid at checkouts.

“We are moving from a situation where we had frictionless trade to one where we have a great deal of friction,” said Dominic Goudie, the federation’s head of international trade. “Any suggestions that these costs will not lead to an increase in food prices should be taken with a really hefty pinch of salt.”

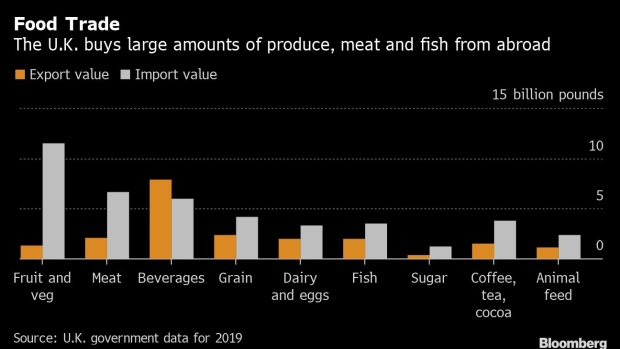

The U.K. buys about half its food from abroad, with the bulk of those imports coming from the European Union. Even before Brexit, food insecurity was on the rise in the U.K., and the pandemic has snarled supply chains.

As suppliers, already squeezed by thin margins, count the new costs of the split from the bloc, the question is who is going to bear the brunt. Estimates from the industry-funded Agriculture & Horticulture Development Board show expenses increasing 5%-8% for livestock products and 2%-5% for crops trade.

“There could be a tempestuous set of discussions to come between suppliers and supermarkets, who are ever-aware of the need to be price-competitive,” said Will Hayllar, a partner in the consumer goods practice at OC&C Strategy Consultants Ltd. in London.

The double whammy of the virus’s economic fallout and the extra Brexit costs could worsen the U.K.’s food insecurity, said Mark Curtin, chief executive of London-based The Felix Project, a food-waste redistribution charity.

The group provided the equivalent of almost 21 million meals last year, and that’s expected to jump to 38 million this year. To accommodate those needs, it’s opening a 9,000-square-foot warehouse in East London later this year.

“We are already facing huge demand,” Curtin said. “This will only be further exacerbated because of the need to help people who are finding it difficult to afford quality food.”

Any border bottlenecks would add to the trade disruptions seen before Christmas, when France temporarily halted traffic due to a new coronavirus strain and created miles-long backups that stranded drivers for days. The port chaos has left European freight forwarders rejecting contracts to take loads into the U.K. due to fears the scenario will repeat itself post-Brexit.

Simon Lane, owner of fruit and vegetable importer Fruco Plc, said transport costs have soared in the aftermath of last week’s debacle, and any holdups for those cargoes would contribute to higher prices for wholesalers, retailers and shoppers. The U.K. imports such crops as citrus and cauliflower this time of year.

“There will be some disruption because there’s a change in the rules,” he said. “The first two or three weeks of January could be a little bit turbulent.”

Yet some argue that shoppers won’t see much of a difference at the cash register since threatened no-deal tariffs averaging 18% won’t materialize. Any administrative fees for trade will “hardly be felt” by consumers, John Allan, chairman of Tesco Plc, the U.K.’s biggest supermarket chain, told the British Broadcasting Corp.

Retailers also will try to avoid boosting prices as the recession makes shoppers increasingly savvy about finding deals, said Sarah Baker, senior strategic insights manager at Warwickshire, England-based AHDB.

“The only anticipated changes will be border control and logistics costs, which I don’t expect to be transferred to the retail shelf,” Tosin Jack, commodity intelligence manager at researcher Mintec Ltd. in Bourne End, England, said in an email. “I expect that other parts of the supply chain will bear any additional costs.”

U.K. Border Crisis Risks Fruit Supply While Meat Piles Up

Supermarkets have stockpiled key goods, but there are concerns about fresh-produce supplies as shippers adjust to new border protocols, Andrew Opie, director of food and sustainability at the British Retail Consortium, said in a statement. The U.K. has planned a six-month grace period for customs checks, while the EU hasn’t agreed to the same, meaning food-filled trucks still may get snarled on that side.

Leaving the bloc also adds challenges for British producers, as most workers processing meat and picking crops hail from elsewhere in Europe. The end of freedom of movement risks raising prices if there’s a labor shortage, according to a Parliament report.

The government will triple visas for seasonal workers, though berry growers said it’s too early to gauge if that’s enough.

“It’s good news for the industry that a deal has been reached,” Baker said. “But it’s inevitable that changes lie ahead.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.