Dec 3, 2019

Homebody in a Hoodie: Hedge Fund Founder Builds Quant Paradise

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Steven Schonfeld is a hedge fund billionaire of a different breed.

He’s almost always in a hoodie, drawn from a closet full of them. He shuns the Wall Street crowd. You’ll never see him at a gala in Manhattan or at Davos or Aspen. Mostly he stays home in Old Westbury, New York.

“Between family, golf, gin rummy and friends, that’s my life,” Schonfeld, 60, said in an interview at his office in New York, wearing a black Supreme hoodie, sweatpants and running shoes. “I’m a homebody.”

Schonfeld also built a growing hedge fund business of a different sort. He picked a close friend from his days at Emory University and a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. alum to run it, serving as a mentor and having patience with their missteps. That engendered loyalty. In another unusual move, he let his quant traders keep what they cherish most -- intellectual property -- as long as they exclusively manage the firm’s capital.

The culture at Schonfeld Strategic Advisors, where traders strive for consistency rather than big wins and rarely get fired, has produced an enviable record in an industry struggling to outperform the broader market. The multi-manager firm has returned an annual average of roughly 20% over the past six years, almost double that of the S&P 500 Index, putting it in the top echelon of hedge funds.

“Any amateur can make money,” said Schonfeld, who talks in short, fast bursts. “But how you make it, and how consistent it’s going to be, are what matter.”

Schwarzman’s Neighbor

In other ways, “Schony,” as his gin pals call him, is just like any other tycoon. He’s worth about $1.3 billion, according to estimates by the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. He spent about $20 million to build a golf course, designed by Rees Jones, next to his Old Westbury estate. On Tuesday, he and his wife Brooke closed on a mega-mansion in Palm Beach, Florida, with the Atlantic Ocean on one side and Intercoastal Waterway on the other, for $111 million.

That plants the couple in the same neighborhood as fellow billionaires Ken Griffin, Paul Tudor Jones and Steve Schwarzman, as well as President Donald Trump, whose Mar-a-Lago resort is less than a mile north.

Schonfeld, who plans to remain a New York resident, rejected the notion that they bought the property to make a splash. He said he hopes the 10-bedroom, 84,626-square-foot estate will lure his three young daughters -- Sadie, Tyler and Hadley -- back home after they go to college.

If Schonfeld has a gift, it’s for numbers.

Employees marvel at his mental math, particularly an ability to calculate probabilities and apply them to almost everything. When the firm was making plans to expand to Asia last year, Schonfeld asked Andrew Fishman, the company’s president, and Chief Investment Officer Ryan Tolkin to develop probabilities of success and upside and downside ratios to four different paths, including an acquisition and building a unit from scratch. They wound up buying Folger Hill Asia, providing the firm with some of its top fundamental equity traders.

“He has always understood the probabilities associated with a particular decision,” said Fishman, who met Schonfeld some 40 years ago at Emory, where they played 3-on-3 tournament basketball together. “He understands there may be losses. But if you have the probabilities in your favor, over time you will be successful.”

Read more: Billionaire Schonfeld lures hedge fund talent to grow wealth

Schonfeld’s obsession with numbers began as a kid growing up on Long Island, delivering newspapers and pizzas and admiring his father, who ran his own garment business in New York. At age 9, he memorized all the statistics on baseball cards for the San Francisco Giants and then recalculated the averages in his head to make sure they were right. These days, when he’s courtside at New York Knicks games, he quickly works through changes to the betting spread at halftime based on first-half results -- no easy task.

During the interview, he sprang from his chair to show a reporter the updates he gets every 10 minutes on his smartphone with the performance numbers of his 80 trading teams.

“I never miss a 10-minute reading,” said Schonfeld, laughing at his own teenager-like phone habits. He also meets with Fishman and Tolkin twice a week for breakfast and talks with them daily about the business.

Schonfeld started out in 1988 with $440,000 from working as a stockbroker and built a short-term trading business with more than 1,000 employees. His firm was one of the first to use the strategy, taking advantage of volatility with bets that lasted a few hours to a few days. He made $200 million in 2000 at the peak of the dot-com bubble. The market crash in 2001 produced the first of two down years for the firm.

Early Mistake

Schonfeld pivoted into quant trading as it was taking off in 2006. He saw that the faster computer-driven strategies were getting in the way of his traders and figured only the best of them would succeed over the long run.

The firm made a mistake as it morphed into a quant shop. Early on it relied too much on a single technology as the core of its data research environment.

“It cost us a certain amount of money,” said Tolkin, who worked on Goldman’s corporate credit trading team before joining Schonfeld in 2013. “We have recognized that there are multiple ways to do things and we have to be more flexible about how we ingest, clean and store data to create an environment that our quants and teams can more successfully gather data from.”

But the successes have far outweighed the failures.

Schonfeld made another $200 million off volatility during the 2008 financial crisis, and used the dislocation that followed to recruit quants, luring them with capital to start a firm, a data platform to tap and the right to keep their intellectual property.

“Whether you did it on my dime doesn’t matter,” Schonfeld said. “You were the brilliant one creating all this. You should own it.”

Quant Teams

The offer helped Schonfeld compete for talent against bigger multi-manager firms that kept their traders’ handiwork. Quantbot Technologies joined Schonfeld in 2009 as one of its first quant teams. The firm extended its agreement to run Schonfeld’s capital through 2027 -- underscoring his ability to retain top talent.

The arrangement also provides protection from regulators who fined Schonfeld in 1999 for trading violations and a decade later for making round-trip trades to hide capital shortfalls. Almost all of Schonfeld’s 22 quant teams are in external firms and hold their own registration with regulators, which means they’re responsible for their own violations. Most of the fundamental equity teams are internal and come under Schonfeld’s beefed-up compliance regime.

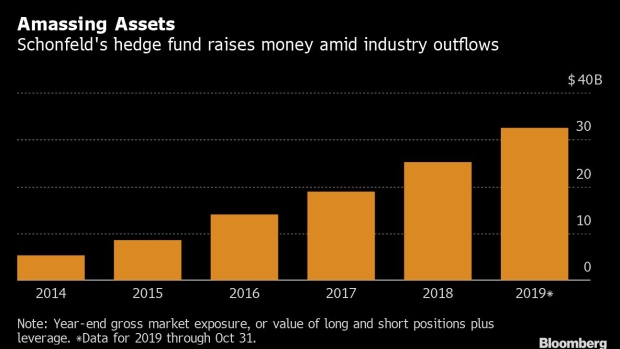

Quants are now the backbone of the global business, deploying half of the firm’s $33 billion in gross market value, which includes long and short positions and leverage. Since 2016, when the firm converted to a hedge fund from a family office, it has raised $3 billion in outside capital, including a round this year, as the industry grapples with outflows.

Schonfeld credits his good run to old-school values of being patient and a mentor to staff -- the same qualities that work well in competitive gin.

Decades ago, after he won more money during a two-year stretch than four better players, they asked how he did it. He told them their mistake was to scold their partners for making bad plays.

“I don’t second guess,” he recalled telling them. “They can make the worst play and I say, ‘I would have done the same thing.’ Because of that, they play infinitely better on my team.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Vincent Bielski in New York at vbielski@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sam Mamudi at smamudi@bloomberg.net, Peter Eichenbaum, Josh Friedman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.