(Bloomberg) -- Protests that began in Hong Kong in June over a bill that would allow extraditions to China have spawned near-daily events that have focused global attention on the city and its relationship with Beijing. The world watched as protesters clogged the airport, forcing authorities to cancel flights. The civil disobedience could affect U.S.-China trade-war negotiations, and many people—including White House officials—have wondered if China will mobilize its forces to gain control.

The political paralysis and unrest has already taken a toll on the economy. And it has also left readers with many questions, from how this all started to how long it will last—and how it will end. Here are the top questions asked by readers through our WhatsApp service.

Was there a trigger that really caused things to escalate?

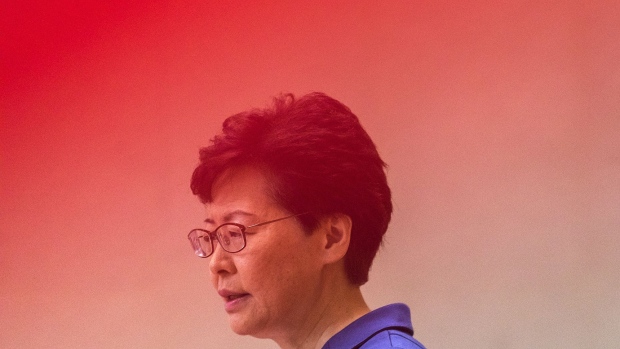

Yes. In February, Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s government proposed legal changes to allow the transfer of criminal suspects between jurisdictions with which it lacks formal extradition agreements—including the mainland. Lawyers, activists and members of the city’s vaunted business community quickly expressed alarm and cautioned that it threatened both Hong Kong’s autonomy from Beijing and its status as a safe place for international firms.

Authorities scaled the bill back but still aimed to push it through by the end of the legislative period in July. On June 9, hundreds of thousands of people marched through the city’s financial hub in opposition to the proposal, kicking off the movement.

Are there other reasons people protest?

Economic frustration is a big one: Hong Kong is one of the world’s most densely packed cities with some of the highest living costs anywhere, particularly when it comes to property. Since their inception, the protests have morphed into a wider anti-government movement with a list of demands that include Lam’s resignation, an independent inquiry into police violence while dispersing people and the release of demonstrators detained at rallies throughout the summer—dozens of whom face up to 10 years in prison on a colonial-era rioting charge. Some activists are also making a push for electoral reform, a subject that triggered the Occupy movement back in 2014. They want direct elections for the chief executive, who is currently selected by a group of political and business elites.

Is Hong Kong’s time as a premier business hub over?

The political crisis risks pushing Hong Kong deeper into an economic slowdown that had already been triggered by the U.S.-China trade war. Beyond GDP, the worry is that the conflict also damages Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe and reliable commercial hub. The city sells itself as a business-friendly environment and one of the world’s most open economies, so anything that challenges that narrative would be a setback. Still, Hong Kong has bounced back from past crises, such as the SARS scare or Asia financial crisis, and it remains an important source of capital for China.

Will its currency get unpegged from the U.S. dollar?

There are no indications that the pegged currency arrangement is set to change. The system that pegs the Hong Kong dollar to the greenback at a rate of about HK$7.80 has been in place since 1983, with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority intervening when the trading band is tested.

Are money and people starting to move out?

It’s not clear how much money is leaving Hong Kong, because any shift has yet to show up in official data. What we do know is that the real estate market is mixed. While office vacancy rates in central Hong Kong soared to a three-year high in July, demand for residential property is holding up. There’s no evidence of a mass exodus from the city at this point, but some citizens who have the means to leave are headed to neighboring Taiwan. Hong Kong’s large expatriate community could also see numbers decrease if people decide it’s become too unstable to do business.

How do the protests stack up with others in Hong Kong’s history?

The protests have drawn the largest crowds and worst violence in the city since it was returned from British rule in 1997. Police are using more tear gas and rubber bullets to subdue demonstrators compared with what was used during the pro-democracy Occupy movement in 2014, the last major bout of unrest to grip the city. Back then, officers fired 87 canisters of tear gas at protesters over 79 days. This time around, they’ve deployed more than 1,800 tear gas rounds from June 9 to Aug. 6, along with about 300 rubber bullets—some at close range. Demonstrators have also upped the ante, shutting down the city’s main airport.

What are the demographics of the protests?

They’ve largely been fueled by young people, including students on summer break from local universities and even high schools. But the makeup of any given demonstration depends on its nature. Initial peaceful mass marches called by the Civil Human Rights Front, a more moderate organizer, saw hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of Hong Kong life take to the streets: families, the elderly, children, students, professionals, even some expats. As the movement evolved, rallies became smaller and more frequent, and, in recent weeks, more violent. While people as young as 15 have been arrested, families, children and seniors tend to keep their distance.

What are China’s options moving forward?

Despite fears among some Hong Kongers that Chinese forces will be dispatched to restore order, a repeat of Beijing’s bloody crackdown on protesters in Tiananmen Square 30 years ago is unlikely. President Xi Jinping could, in theory, do away with Hong Kong’s autonomy and activate the thousands-strong People’s Liberation Army garrison in the city. But the fallout of such a move could be a lot higher than dealing with the political and economic repercussions of the protests. One major factor is his trade war with U.S. President Donald Trump, who has linked Hong Kong’s unrest to negotiations, as well as threats from American lawmakers to end the city’s special trading status.

How might things end?

With no end in sight to the movement, that depends on how much each side is willing to concede. Demonstrators have said they won’t stop until Lam has met their key demands, including:

- her resignation

- an independent inquiry into police tactics

- the release of detained protesters

- and the extradition bill’s formal withdrawal.

China’s top agency overseeing Hong Kong rejected such an inquiry into the unrest in early August, even though it was one of the few protester demands supported by the city’s business leaders. Lam extended an olive branch on Aug. 20 by pledging to establish a platform for dialogue, investigate complaints against police and institute a wide-ranging fact-finding study into the summer’s events. But protests are still planned for the coming weeks.

To contact the authors of this story: Karen Leigh in Hong Kong at kleigh4@bloomberg.netEnda Curran in Hong Kong at ecurran8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ten KateLisa Fleisher

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.