The pandemic helped make Canada one of the world’s hottest real estate markets. With a portfolio of more than 100 houses, that meant a windfall for Brady McDonald.

“My net worth has obviously gone up a lot, just based on what’s happened this year, because the market’s gone berserk,” said McDonald, a former arborist who started acquiring single-family homes in the small city of Barrie, Ontario, in 2015, and now says he has a net worth “in the millions.”

“We have a housing crisis here,” he said from Barrie, where prices have gone up almost 40 per cent in the last year. “The demand for housing is not going down. So there’s always opportunity.”

But in a country that faces one of the world’s most acute housing shortages, investors like McDonald are coming under increased scrutiny. Concern is growing that the professionals are crowding out first-time buyers and would be quick to sell if property values start to slide, which could threaten the economy.

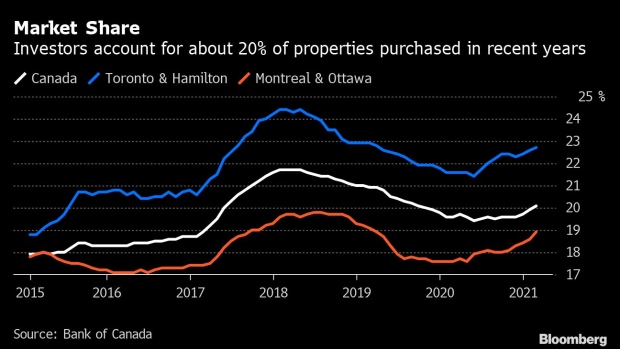

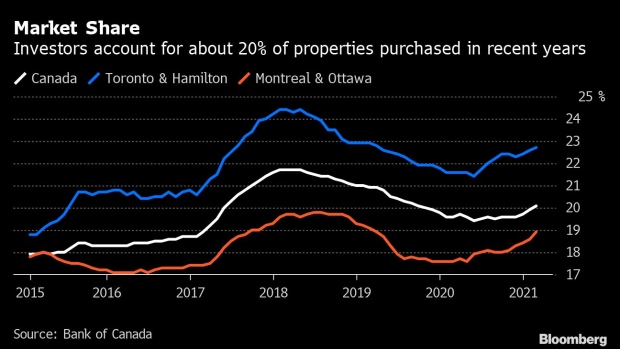

Investors account for about a fifth of new mortgages in Canada -- the same share that prompted a crackdown in the U.K., and roughly five times the rate in the U.S. -- stoking debate over whether homes should be viewed as assets, or just places to live.

“The moment we want houses to be good investments is the moment we want prices to grow faster than local economies and local earnings,” said Paul Kershaw, a professor at the University of British Columbia and founder of Generation Squeeze, a group that advocates for issues important to young people, including accessibly priced housing. “That’s a recipe for unaffordability.”

At its heart, the investor debate is one about the value of owning a home versus leasing. While investors purchase properties that may otherwise go to buyers who would live in them, they typically make the homes available to renters.

But generations of Canadians have been raised to believe that owning a home is the surest way to financial security -- at almost 70 per cent, the country’s homeownership rate is above those of many peer nations. There’s also the widespread conviction that a single-family detached house is the best place to raise a family.

That thinking also prevails in the U.K., which began reining in housing investors after they started accounting for about a fifth of new mortgages in 2015. Politicians were concerned that first-time homebuyers were getting outbid, and the Bank of England said investors might be more likely to sell in a crash than owner-occupiers.

That led to new rules toughening standards for investors to qualify for loans, and tax changes that made investment properties more expensive to buy and less profitable to hold. The share of mortgages going to investors in the U.K. has subsequently fallen to just under 12 per cent.

“There is a role for investors, but there is a much more limited role in this market because they are competing with aspirant owner-occupiers,” said Alan Brener, a lecturer at University College London who has written a book about mortgage lending and government policy in the U.K. “The competition drives up the asset price for what’s available.”

While there’s no doubt competition for houses in Canada is intense -- bidding wars resulting in deals for six figures over asking have become routine -- policy makers so far have given no indication they plan to impose curbs on domestic investors.

“Determining the precise level at which investor activity should be a cause for concern is difficult and requires further study,” the Bank of Canada said in an emailed statement, adding that its researchers plan to publish further analysis later this year.

While the central bank went on to echo the Bank of England’s concern about mass sales in a downturn, it said Canada’s current investor involvement may not be comparable to what prompted the U.K. to act because the countries collect data differently. The Bank of Canada also argued investors contribute to a healthy housing market by increasing options for renters.

One example may be Brady McDonald in Barrie, about a 90-minute drive from Toronto with a population of roughly 140,000. Rather than immediately lease out the houses he buys, McDonald renovates them to add extra units, turning a property built for one family into space for two or three, which also maximizes his income.He’s able to hold stakes in so many houses because most are 50-50 joint ventures, where a partner brings the capital and McDonald contributes his expertise in property conversions and management.

The strategy -- a common one among Canada’s investors -- works because the country needs all the housing it can get: A recent report by the Bank of Nova Scotia showed it had the fewest residential units per capita of any Group of Seven nation.

“I think we need to get away from this ‘Everyone has to own a home,’” said Jeremy Kronick, a researcher at the C.D. Howe Institute, a Toronto-based think tank. “Everyone has to have a home to live in that they can afford and that meets their needs. But it’s not clear to me that you have to have 70 per cent ownership.”

Critics like Generation Squeeze’s Paul Kershaw say that having investors convert detached houses into apartments isn’t the best way to serve Canada’s renters, who risk losing their home when the landlord decides to cash out.

Though institutional investors have become more active in acquiring Canadian apartment buildings in recent years, the country so far hasn’t seen the kind of large-scale buying and renting of detached houses that’s become more common in the U.S. One firm’s recent efforts to pursue such a strategy are already proving controversial.

In the meantime, Canada’s smaller investors may start to find themselves priced out of the market by the pandemic boom, as rents -- which are tightly controlled by provincial governments -- fail to keep up with the ballooning costs of buying and maintaining homes.

“Single rental income typically won’t cover the expenses of a property, and it’s becoming harder with even duplexes in some areas,” said Vlad Maevskiy, an owner of 14 properties in Toronto’s suburbs who quit his IT consulting job last year to focus on real estate full time. “It’s hard to compete with somebody who is prepared to pay ridiculous money over asking.”