Aug 19, 2018

How crises and bailouts have changed Greece’s economy

, Bloomberg News

Greece is about to exit its bailout, a symbolic move past the debt crisis that exploded eight years ago and transformed the country’s economy and the lives of its people.

At the time of the May 2010 aid package -- the first of three -- politicians from euro-area creditor countries argued the crisis was the result of chronic fiscal and economic indiscipline. To justify breaching a “no bailout clause,” loans were tied to strict conditions covering everything from government spending to public administration and justice.

So how has Greece performed?

Economic Hit

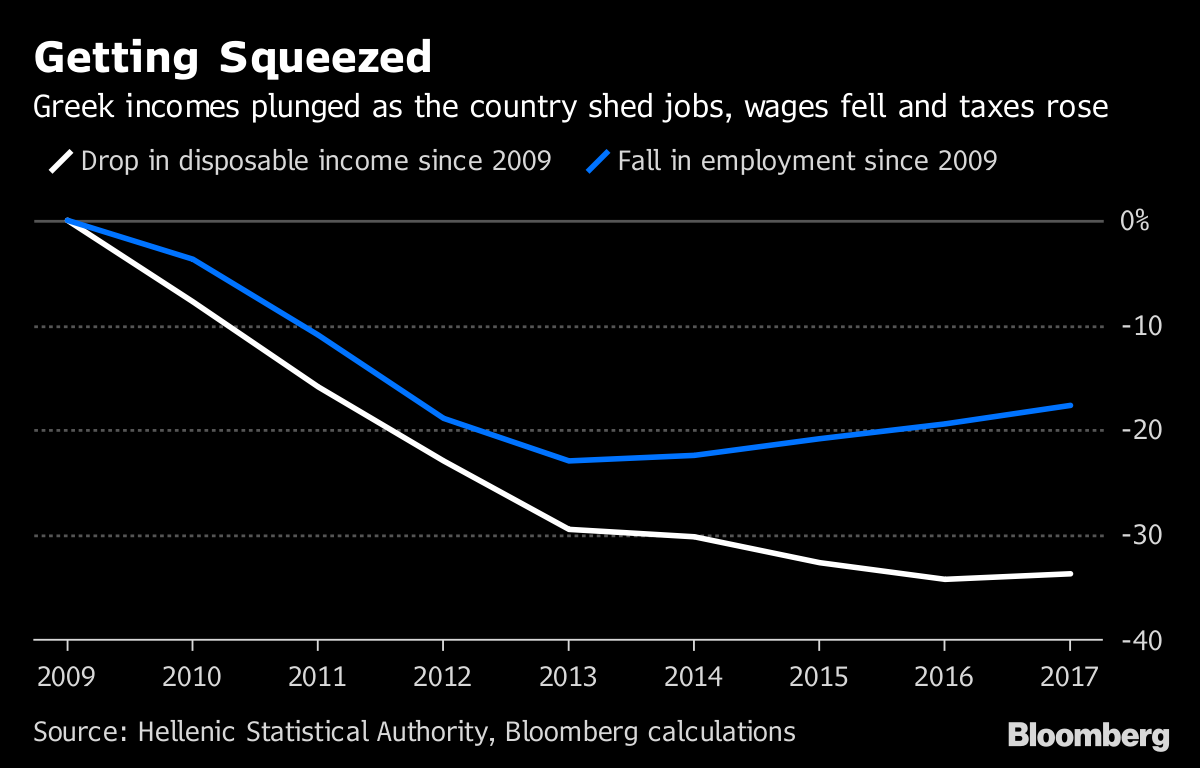

While Greece’s crash rippled far beyond the borders of the country of just 11 million people, the effect at home was particularly dramatic. Economic output fell by a quarter and living standards collapsed after the loss of more than a million jobs pushed unemployment at one point to 28 per cent.

For the country’s creditors, this was the cost of putting economic growth on a sustainable footing.

“The ultimate goal of the financial assistance plan and reforms in Greece over the past eight years has been to create a new basis for healthy and sustainable growth,” Portuguese Finance Minister Mario Centeno, who chairs meetings of his euro-area counterparts, said in a statement on Monday. “It took much longer than expected but I believe we are there.”

Public Finances

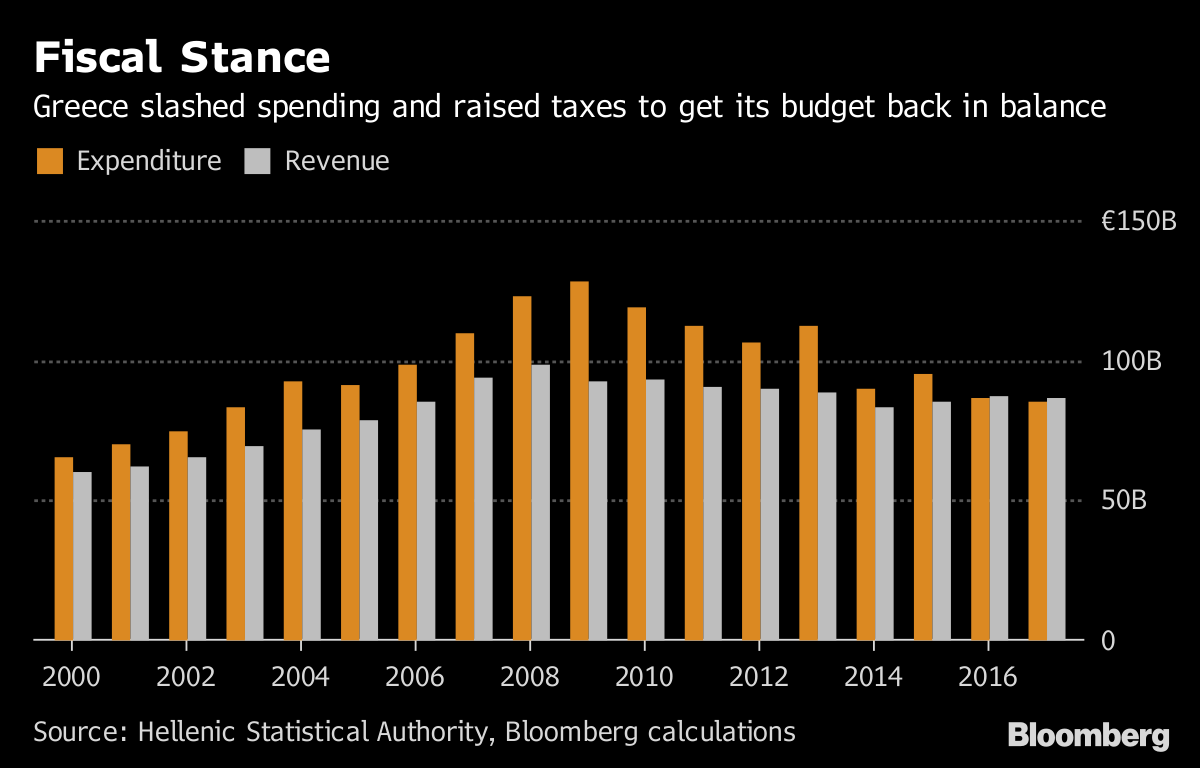

The Greek leg of the global financial crisis was sparked when George Papandreou’s newly elected government revealed that the country had misled the world about its finances and the 2009 budget deficit had swelled to more than 15 per cent of gross domestic product, five times the EU limit.

In recent years, the debate on Greek finances has turned more to the amount of public debt and the fiscal balance excluding the costs of servicing that debt. That’s meant less attention on the fact that for two years now, revenue has exceeded spending and the government has run an overall surplus.

This has been achieved by slashing spending while holding revenue more or less unchanged. But given the extent of the slump, maintaining steady revenue meant a huge squeeze on middle-class Greeks, who’ve had to stump up more and more in taxes.

Public Administration

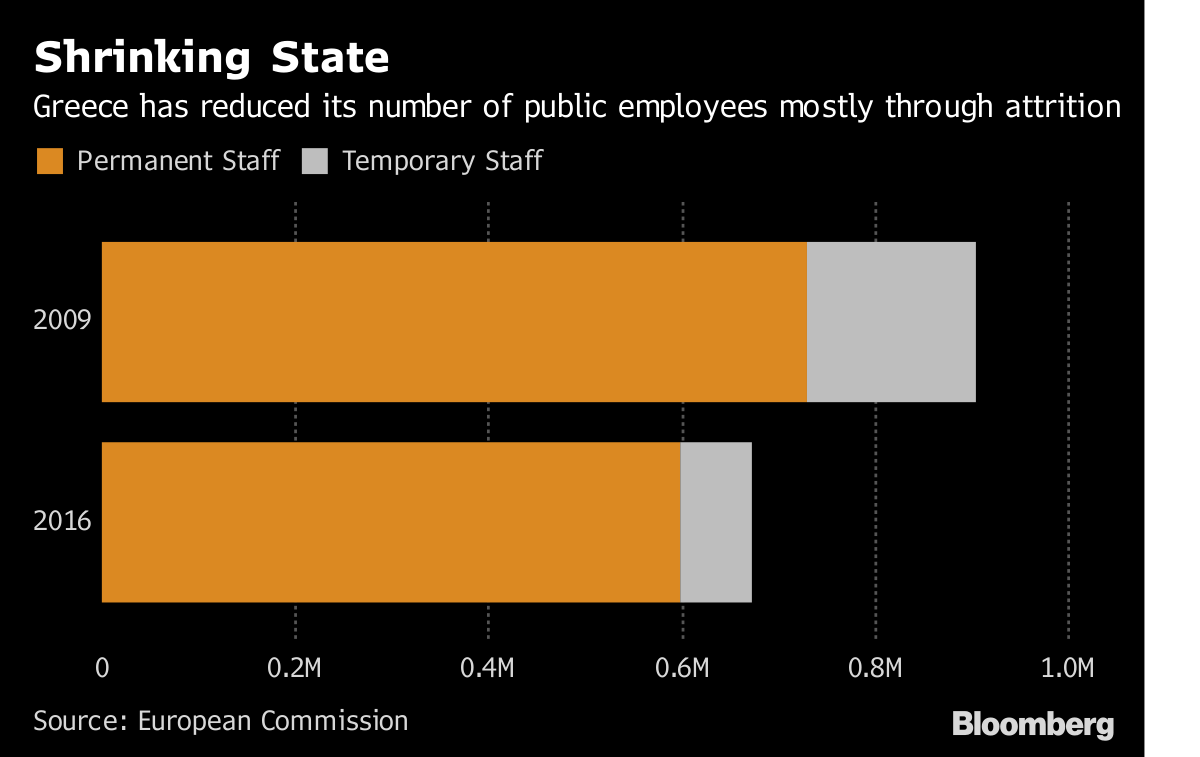

On the spending side, Greece’s fiscal problems were partly caused by an explosion of public-sector jobs in the years before the crash. A refusal to fire workers became an early flash point between the government and the bailout providers.

Those arguments dissipated after Greece shrunk the public payroll by 150,000 jobs by only hiring one person for every five departures and not renewing temporary contracts.

Still, progress has been slow in improving the speed of resolving civil disputes in the justice system, and the burden of red tape has made it harder to attract investment.

Competitiveness

Over the last eight years, a constant refrain from euro-area nations and the IMF was that Greece needs more structural reforms to make it more competitive. Over three bailouts, it’s sold state assets, made sweeping changes to the electricity market and changed regulations covering everything from lawyers to hairdressers.

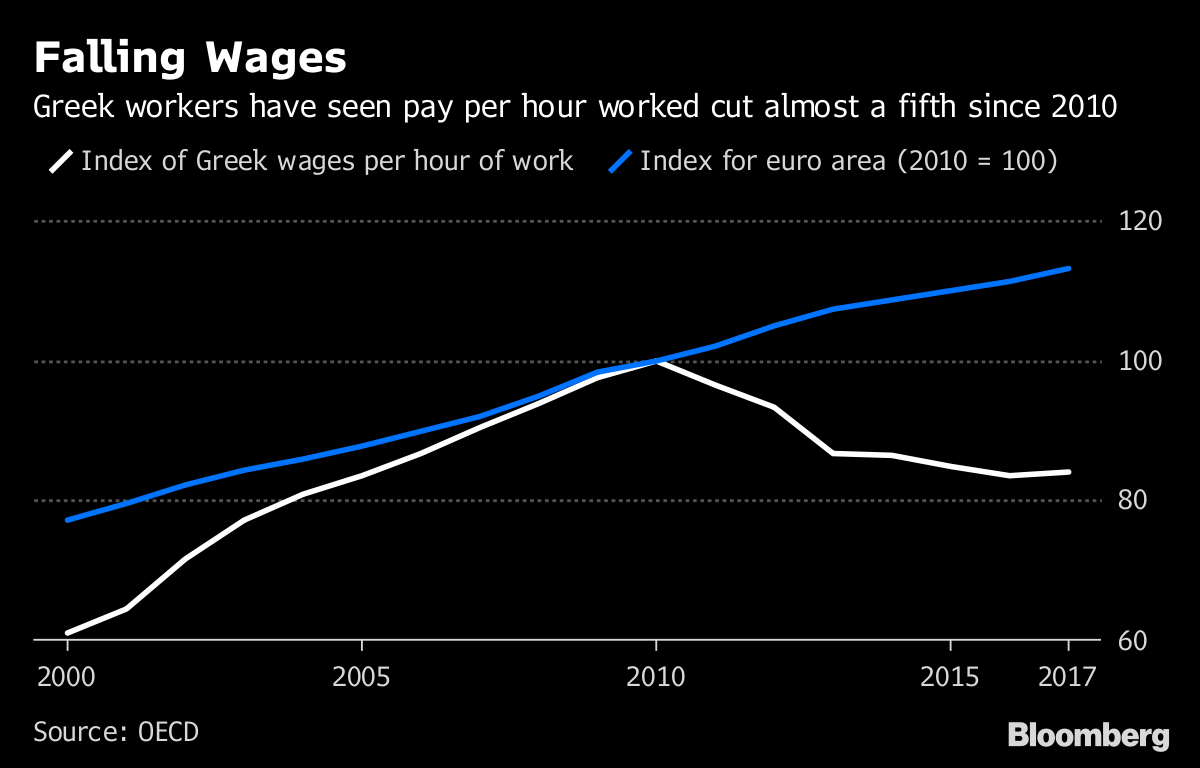

There was also a big fall in labour costs, particularly after reforms to collective bargaining rules and a cut in the minimum wage in 2012. Bailout lenders argue that the drop merely offset the big run-up in the years before the crisis, which wasn’t matched by an increase in the economy’s productive capacity.

Along with rising taxes and the loss of jobs, the hit to wages was a major contributor to the drop in Greek living standards. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras wants to roll back some of the labour reforms after the bailout, including increasing the minimum wage.

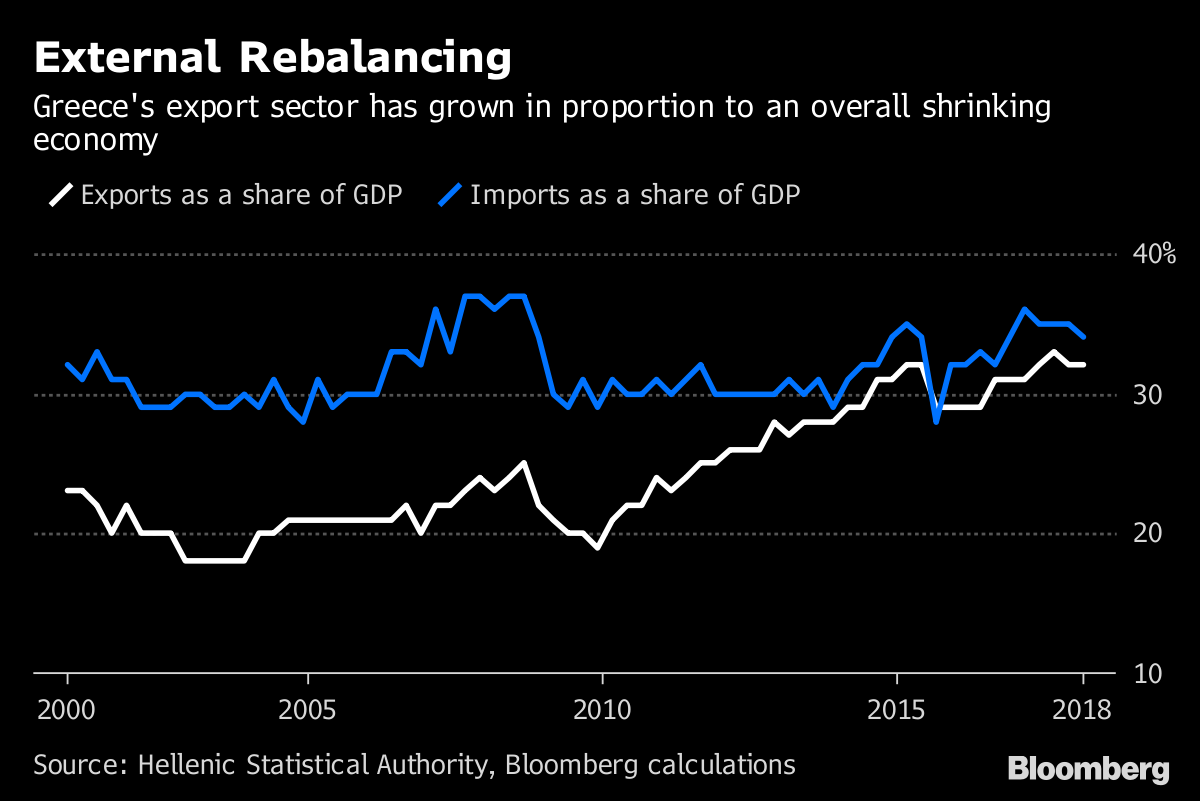

Greece hasn’t experienced the kind of export-led recovery seen in other crisis countries, like Ireland and Spain. But it’s almost eliminated its external current account deficit, as well as increasing exports’ low share of GDP.

Financial Sector

At the outset of the Greek crisis, the country’s bankers liked to argue that their institutions were conservatively run, and that this was a problem born in the public sector. Whatever the truth of the claim, it didn’t take long for a sovereign-banking doom loop to lay the sector to waste.

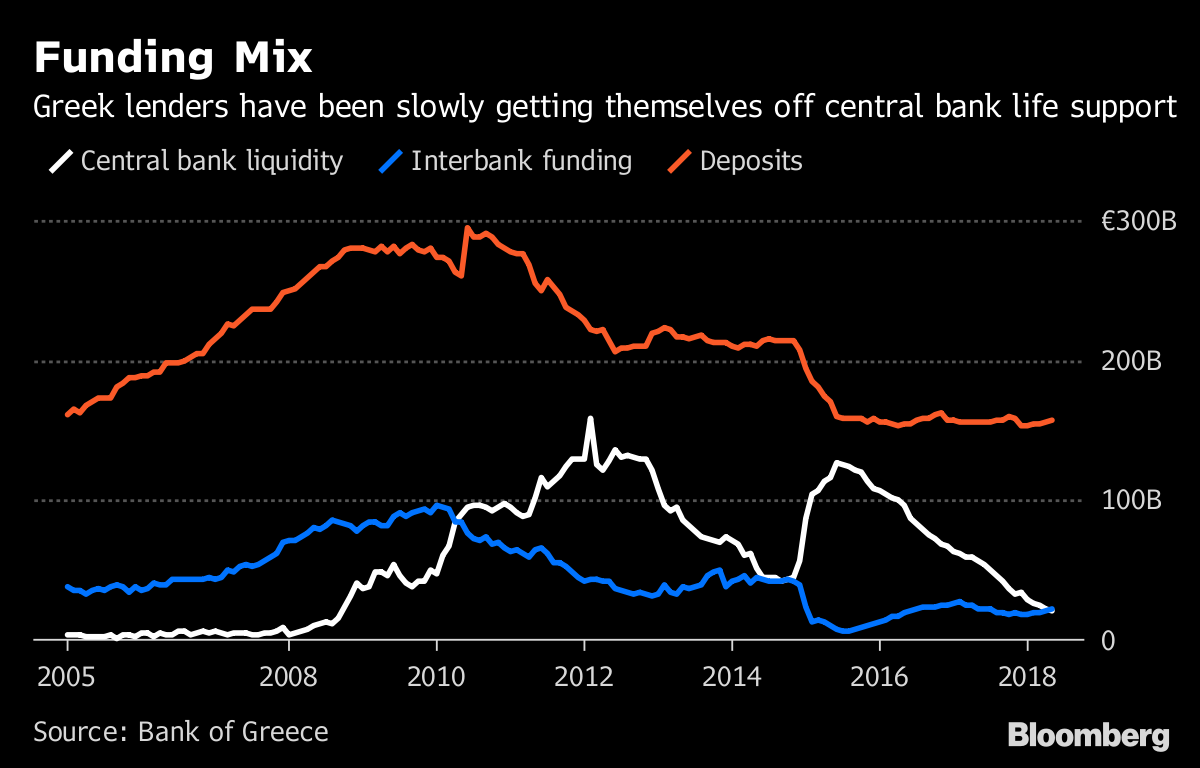

The banks were rendered insolvent for a while after the 2012 debt restructuring wiped out the value of their bond portfolios, and three years later they were shuttered for weeks before reopening with capital controls in place. They’re still dealing with the fallout, saddled with soured loans amounting to almost 50 per cent of their book.

These travails have led to a loss of deposits and interbank funding lines, with lenders kept on life support by central bank liquidity. The need for that emergency funding has steadily diminished and, in the buildup to the bailout exit, it was even surpassed by interbank funding for the first time since the start of the crisis.