Jun 24, 2022

How One Woman’s Hardball Tactics Opened the EU’s Door for Ukraine

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the night train to Kyiv clattered through the darkness, some of Ursula von der Leyen’s team were worried.

The European Union’s most high-profile official was chatting to reporters drinking beer in the luxury car at the back of the train. The aides were fretting about how member states would react to a gesture designed to pressure them into opening the door to Ukraine, according to a person with knowledge of their thinking.

EU leaders had refused to make Ukraine a candidate for membership at Versailles near Paris in March. But less than two weeks after von der Leyen visited Volodymyr Zelenskiy in Kyiv, the Ukrainian president was dialing in to another summit on Thursday night to thank the bloc for starting the membership process.

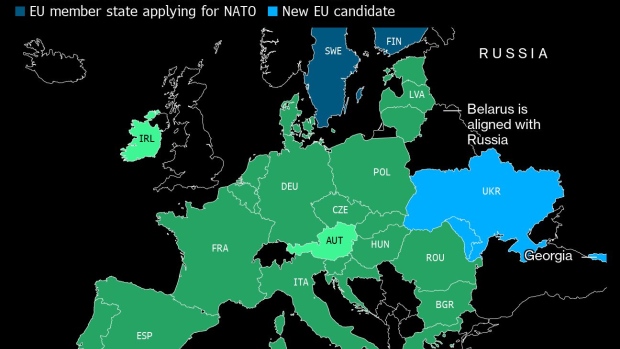

The decision to make Ukraine an official candidate, alongside Moldova, hints at a more assertive European Union, embracing countries on its eastern flank regardless of the threat posed by President Vladimir Putin’s vision of the historic Russian empire.

European Commission President von der Leyen has learnt the lessons of past crises when the EU paid a high price for dithering, observed one senior EU official and is now seizing a moment when taboo after taboo has been cast aside.

There are broader risks to the strategy, though.

It was the prospect of closer relations between Kyiv and the EU that prompted Putin to intervene in Ukraine in 2014 when his forces annexed the Crimean peninsula and the Russian leader has referenced the expansion of NATO to his borders before the invasion of Ukraine in February.

Indeed, in the days before Thursday night’s candidacy decision, Moscow made steep cuts to the gas supplies reaching to Europe, setting alarm bells ringing in Germany, where the country’s industry is particularly reliant on Russian energy. Officials are braced for further retaliation and von der Leyen may be reaching the limit of how far she can push the member states.

But Ursula von der Leyen is a risk-taker.

Despite learning her political craft under Angela Merkel, Germany’s ultra-cautious former chancellor, von der Leyen arrived in Brussels in 2019 with a reputation as someone more likely to ask for forgiveness than permission.

Most famously, as Merkel’s defense minister, she pushed through parental leave for the German military despite the opposition of many lawmakers in her conservative caucus by keeping them out of the loop. It earned her enemies in the Bundestag, but won her the respect of Merkel, who, for all the differences in their ways of operating, recognized that von der Leyen could get things done.

In Brussels, she used similar tactics to push through her signature plan to de-carbonize the European economy, presenting the final proposals just hours before the crucial meetings, giving her commission opponents little time to formulate a considered response.

With her husband back in her native Germany and her seven children grown up, 63-year-old von der Leyen’s Brussels life revolves around her office at the top of the commission’s headquarters. She sleeps in a converted storage room with no windows just a few feet from her desk, according to a person familiar with her set-up, and she shares information with a small group of fellow Germans led by her head of cabinet, Bjoern Seibert.

Cutting commissioners and senior officials out of the decision-making process regularly causes tensions, but it can be effective.

As von der Leyen battled to implement sanctions on Russian oil earlier this month, she presented her plan in the European Parliament before member states had even had a chance to review the details, irritating several diplomats involved.

Brussels Rockstar

But there is also grudging admiration for what she has done. One diplomat involved observed that despite the complexities and pressures of the negotiations, von der Leyen managed to find a position that all 27 members could agree on.

She is the Brussels equivalent of a rockstar – said another -- someone else often needs to clean up the hotel room the morning after the concert.

When the invasion began in late February, many European officials were saying it would be impossible to shut Moscow out of the SWIFT international payments system.

"We will not let President Putin tear down the security architecture that has given Europe peace and stability over many decades," von der Leyen said hours after the invasion. "He should not underestimate the resolve and strength of our democracies."

Four months later, she has helped to broker restrictions that have hit Russia’s largest banks, its coal exports and even its oil, moving more cautious nations like Germany and France closer to the US position and maintaining a united front against Putin. The EU has also hit individuals close to Putin himself, like Roman Abramovich, the one-time owner of Chelsea Football Club, and the former gymnast Alina Kabaeva.

The struggle to push through that sixth sanctions package, and the extensive carve-outs that Hungary won, suggests member states may be reaching the limit of what they are prepared to do to pressure Putin at this stage of the war. And what they are prepared to put up with from von der Leyen.

Irritation in the Capitals

There is chatter in some corners about finding an alternative to replace her as head of the commission when her term expires in 2024, rather than granting her a second mandate, according to people familiar with those discussions.

While she’s there though, von der Leyen is taking opportunities to accrue more power to the EU executive – and to herself.

In April, her team told EU ambassadors that the commission would have day-to-day control of any fund for rebuilding Ukraine, which would potentially total hundreds of billions of euros. And she’s set to secure a bigger say for the commission in the energy market as the bloc speeds up decoupling from Russian fossil fuels.

By recommending conditional candidate status for Georgia, as well as Ukraine’s advancement, von der Leyen’s commission created the prospect that the bloc might one day stretch into the Caucasus, a region Putin considers to be Russia’s sphere of influence.

When she sees that she is getting what she wants, she wants more, said one EU diplomat.

Von der Leyen’s visit to Kyiv came on June 11, when the commission was preparing its recommendation and helped to bring EU leaders around to backing that opinion. In a joint press conference with Zelenskiy she asserted that Ukraine’s membership bid was progressing.

The same day rumors began to circulate that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, France’s Emmanuel Macron and Mario Draghi of Italy would make their own visit to Kyiv. That follow-up trip on June 16 was the real game changer, one diplomat said. After that, other leaders rushed to give their backing too.

Von der Leyen spent an hour and a half with Zelenskiy that day, running through the progress that Ukraine has made in strengthening its democratic institutions and getting the country online, and pressing him on the long list of reforms still to be done, especially on tackling corruption.

Afterward, she and her team went to a hotel room in the Ukrainian capital to take stock and talked about the scale of the task ahead, to integrate the war-torn country in the EU and the delicate work to keep member states on board.

From the window, she could see Maidan Square, where eight years earlier Ukrainians calling for closer relations with the EU were shot and killed by police from the pro-Moscow administration in power at the time.

“I hope that when we look back, we’ll be able to say we did the right thing,” she said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.