Dec 23, 2021

How Shopify outfoxed Amazon to become the everywhere store

, Bloomberg News

How Shopify became the everywhere store

Last February e-commerce company Shopify Inc. replaced the “Ottawa, Canada” dateline that began its press releases and earnings reports with a strange new one: “Internet, Everywhere.” The geographical shift came at the insistence of Shopify’s founder and chief executive officer, Tobi Lütke, who tends to view such matters through the prism of cold, hard logic. In May 2020, only a few months into the pandemic, he’d made the early, seemingly rash decision to terminate the leases on Shopify’s offices in Ottawa and six other cities, declaring that his entire 7,000-person workforce would remain virtual—forever. Shopify, he concluded, was now omnipresent, located with its employees and customers in the digital ether. His senior execs were perplexed at the strange phrasing, but they knew better than to argue.

The dateline thing may be a bit pompous and a little too cute, but after an almost two-year run that’s turned the quiet enterprise-tech company into a global e-commerce power, Lütke has earned some creative license. Since he started Shopify 15 years ago, the company has sold software that allows about 2 million merchants worldwide to run websites—free from the complicated embrace of Shopify’s chief rival, Amazon.com Inc. For US$30 to US$2,000 a month, Shopify offers sellers more than a dozen services to run an online store, from the actual e-commerce website to inventory management to payment processing.

Its technology now undergirds the websites of giant retail chains such as Staples Inc. and Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc.; recently ordained public companies that grew up on the platform, including shoemaker Allbirds Inc. and medical scrubs maker Figs; and the retail side-hustles of Kylie Jenner, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, and other celebrities. But the company’s biggest impact has been at the smaller end of the scale, in the vast constellation of mom and pops, venture-capital-backed startups, influencer mini-moguls, twee entrepreneurs, merch heads, and more obscure outfits, like Offlimits—a two-person New York City startup trying to reinvent, of all things, breakfast cereal.

What Zoom was to corporate America during the early days of the pandemic, Shopify was to small-business owners, many of whom had never sold a single product online until it became the only way they might stay alive. At the time, Shopify, a little-known company powering some 600,000 merchants, was more likely to be confused with the music service Spotify than synonymous with e-commerce. But when businesses everywhere had to close en masse, Shopify armed them with the tools to become instantaneous online stores. While Amazon’s reputation as a vampiric partner to merchants was reinforced in 2020 by sellers’ testimony in front of a congressional subcommittee investigating Big Tech, Shopify suddenly emerged as their biggest ally.

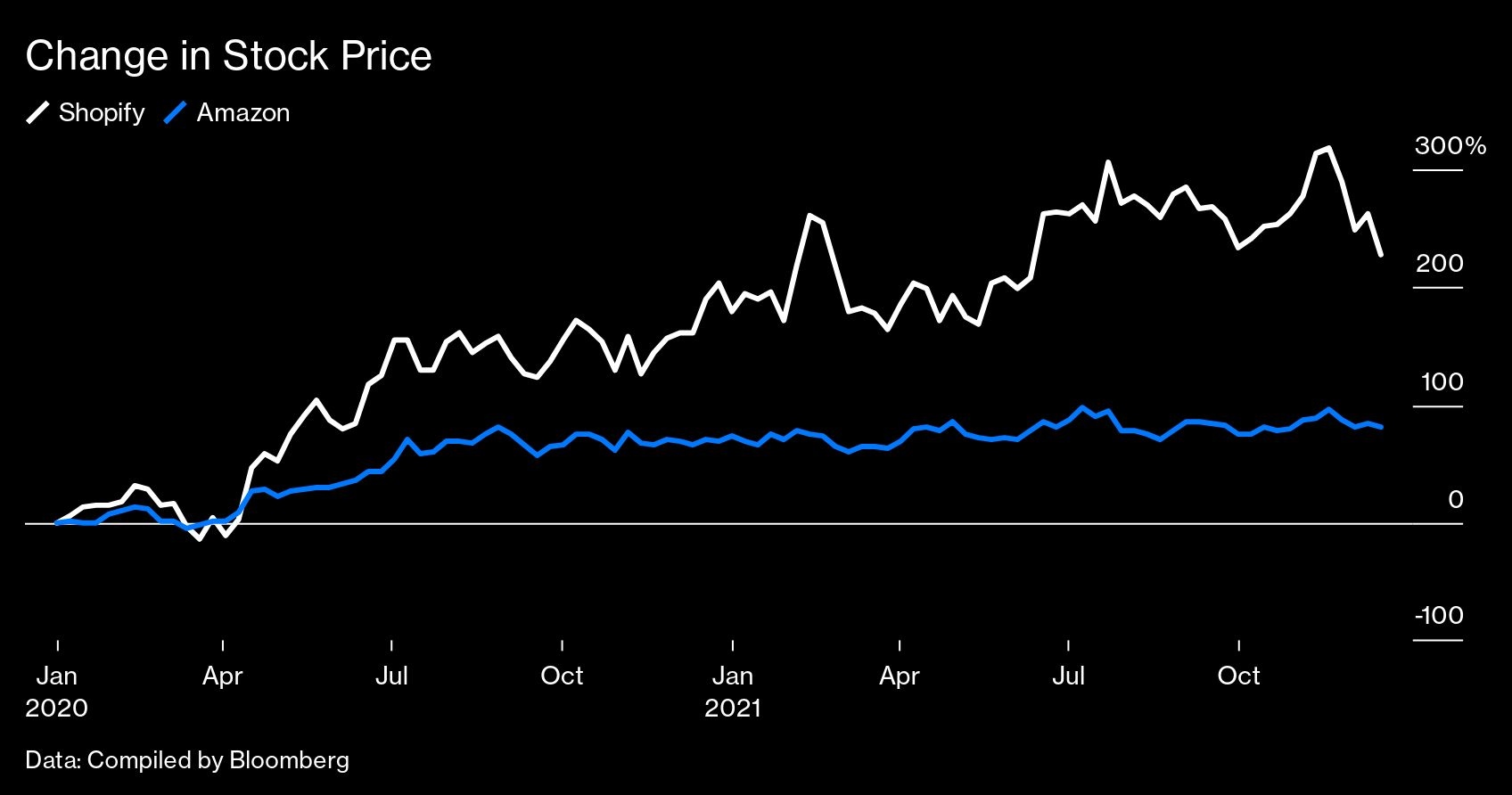

The global quarantine boosted the company’s market capitalization from US$46 billion in early 2020 to US$174 billion today. In 2020 its sales jumped to US$2.9 billion, an 86 per cent increase from 2019. Over the recent Black Friday / Cyber Monday weekend, Shopify merchants brought in US$6.3 billion in sales, a 23 per cent rise from a year earlier. Now Canada’s most valuable company, it accounted for 8.6 per cent of U.S. e-commerce sales in 2020, well behind Amazon’s 39 per cent but ahead of Walmart and EBay, according to EMarketer. “The pandemic just turbocharged them. It’s ridiculous,” says Rick Watson, an e-commerce consultant and host of Watson Weekly, a podcast about online selling.

As the success of Zoom, Peloton, and other pandemic breakouts starts to fade, Shopify is working furiously to keep its momentum going and weave itself into the zeitgeist. Recently it hired a veteran of Kanye West’s Yeezy brand to run a new influencer program, opened a slick entrepreneurs’ hub in Manhattan, teamed with the actual Spotify to help musicians become merch machines, and rolled out a feature that allows shopkeepers to sell unique digital artworks—“I am creating NFTs,” tweeted Martha Stewart, now a Shopify merchant, in October, tagging the company. Pharrell Williams, who sells his skin-care line on Shopify, is a fan, too. “If you’re able to come up here and be part of this platform, you’re in great, great, great company,” the producer-rapper-singer-entrepreneur told a group of business owners over Zoom at the company’s annual conference in October.

Lütke, who decided to develop the underlying tools to build retail websites after shuttering his online snowboard store when he was 24, is now Canada’s second-wealthiest person, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. In the insular circles of tech and retail, he’s become a popular and recognizable figure—41 years old, whip thin, Bezos bald, and never without his trademark pageboy cap (until recently, when he abruptly stopped wearing it amid the ceaseless quarantine). “It was defensible when I actually went outside at times,” he says.

In a sense, Lütke and his colleagues are the opposite of Jeff Bezos’ army of techno-capitalists. Amazon, which has enjoyed its own COVID-fueled boom, celebrates the almighty customer. It will happily risk alienating small businesses by knocking off their products or soliciting new competition, if it means lowering prices and accelerating shipping times. Shopify, on the other hand, has a romantic view of the merchant—its executives rapturously extol the virtues of “democratizing commerce” and “making entrepreneurship cool.” If Amazon’s devotion to customers and an infinite selection earned it the nickname “the everything store,” Shopify, as its new dateline suggests, wants to be the everywhere store.

A few years ago, Lütke sensed there was an advantage in contrasting Shopify with its widely feared competitor, remarking, “Amazon is trying to build an empire, and Shopify is trying to arm the rebels.” But it’s difficult to argue you’re still an insurgent force when you have a Death Star-size market cap. To keep the rebel alliance intact, Lütke has to make Shopify more useful to the world’s largest retailers, while helping smaller ones caught in the grip of supply chain shortages and inflation.

At the same time, he has to contend with growing pains at home, including C-suite turnover and questions about whether Shopify should get into the most laborious parts of e-commerce, like shipping. Winning over hordes of retailers by giving them a simple and sturdy online presence, it turns out, was the easy part. “I have huge blind spots just because, I mean, I grew up as a nerd, programmed all day long, and spent my entire 20s building Shopify,” Lütke says during a two-hour interview at his one-person office in Ottawa. “I have some catching up to do about how everything kind of fits together.”

Trying to talk to Lütke about pretty much anything is a perilous journey into an intellectual labyrinth built out of management books and discursive thoughts. His current fixations include the concept of the Trust Battery, which is how he gauges his confidence in employees, along with the hypothetical that one of the most critical pieces of technology, the web browser, couldn’t be introduced today because Apple Inc., Google, and other app store owners wouldn’t allow it. In any Lütke discussion, you’ve got to be ready for sentences like “I know how to exoskeleton my time” and “I fundamentally find nondeterminism more interesting than determinism.”

Before the pandemic, like a lot of tech CEOs and investors, he read Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder and became fascinated by chaos engineering, the idea that allowing for both unanticipated calamities and intentionally introduced failures can make people and organizations stronger. “Nothing can become truly resilient when everything goes right,” Lütke says.

He couldn’t resist testing the theory on his own company. Among other quirks, he’s wary of needless gatherings, so he started periodically exploiting “god mode” on his employees’ calendars and deleting regularly recurring meetings. Then, in 2017, he sent everyone home to work virtually for a month, just to see what would happen. The experience, partially dependent on Skype, was lacking. “The tools were terrible,” he says.

Shopify eventually moved into 10 floors in an Ottawa skyscraper. A go-kart track snaked through one floor. For a while there was a collection of gallery-size portraits depicting Lütke and the rest of his early executive team wearing Napoleon-era military regalia. The office also had a virtual-reality game room, pingpong room, and yoga studio. Employees said it was a great place to go to work every day.

But Lütke wasn’t over his obsession with remote work. As an early contributor to Ruby on Rails, an open source programming language, he’d collaborated for years with people he’d never met in person. And Shopify’s headquarters may as well have been located off the grid when it came to trying to recruit experienced execs and hotshot engineers who would pick up and move to the Canadian capital (average low in December: 18F).

When the pandemic sent his thousands of employees home, Lütke decided to solve all these problems at once. Shopify’s fancy offices, he decreed in May 2020, just as e-commerce sales were taking off amid quarantine, would close forever, and the company would be a digital company—headquarters: Internet, Everywhere.

Lütke was only too happy to turn inward. He rented an apartment near his home and transformed it into that office for one, accented with old snowboards and an original Macintosh computer. His recruiting efforts immediately got a boost. Shopify hired one executive from Facebook and another from Slack; both have remained in Silicon Valley. Others who’d moved to Toronto relocated back to the U.S. to be closer to family—and sunlight. “For the first time in our 15-year history, our global talent pool was not limited to who is willing to move to Ottawa, Canada, or Toronto or wherever, but rather who wants to come in and help with the future of commerce,” says Lütke’s extroverted frontman, Harley Finkelstein, the company president and a telegenic veteran of Canada’s Shark Tank version, Dragons’ Den.

Not everyone was happy. Some employees loved the tightknit culture and fraternizing of the physical office. “I was legitimately opposed to it and thought it was the dumbest idea,” says Kaz Nejatian, a Facebook alum who joined Shopify in 2019 as vice president for merchant services. Nejatian, who felt Shopify’s culture was dependent on in-person collaboration, eventually came around—but others did not. “I was into the humans and the people I worked with at Shopify,” says Craig Miller, who was chief product officer at the time. “I remember thinking that it felt like a giant loss.”

There were other unanticipated consequences. Extending his CEO arm virtually into discussions, and sometimes reprimanding underlings for mediocre work in his blunt way, earned Lütke the internal nickname “Tobi the Tornado.” He says the moniker is “a little bit irritating” and challenges anyone “to point out the moment I raised my voice.” But that’s just it: You can’t gauge the volume of an online comment. “Slack exacerbated things,” Miller says. “In a company with thousands of people, they can all see Tobi laying into someone.”

Then, amid the global protests in May 2020 stemming from the killing of George Floyd, remote Shopify employees rushed to express their emotions on Slack. Lütke had long encouraged a diversity of perspectives, with company values such as “conformity kills creativity” and “act like an owner.” On a channel called #belonging, employees debated various issues related to race and inclusivity. But when someone discovered an emoji of a noose had been uploaded to the Slack, according to a report at the time by news site Insider, the discussion got heated, and Lütke decided it was becoming a dangerous distraction. Rather than use it as a moment to open up dialogue with his staff, he converted the channel into read-only.

Then he wrote an internal memo to senior execs, declaring that Shopify “is not a family … and not the government. We cannot solve every societal problem here.” Although the memo, which predictably contained esoteric references—this time, to Lewis Carroll and concepts in electrical engineering—wasn’t meant for broad distribution, it was leaked to the media and criticized by outsiders as unduly harsh. Lütke doesn’t disavow his memo but says, “I have to probably look at my messages once over, you know.” (Says his wife, Fiona McKean, of her husband’s emotional intelligence, which she says has come a long way since they met 20 years ago playing the online fantasy game Asheron’s Call from different continents: “You can’t logic your way through cultural upheaval.”)

But Lütke wasn’t budging on his principles and, during the crises of 2020, moved to exert more of a grip over his company, not less. In the fall, Miller, the chief product officer, left after nine years; Lütke swiftly absorbed his responsibilities. Four other senior execs, including the chief technology officer and top HR exec, also exited over the next few months, as bonds frayed and internal camaraderie dissolved. If Shopify was going to navigate out of a “new box that we don’t understand yet,” as Lütke wrote in the leaked memo, he was going to have to be firmly at the helm.

In 2015, after 10 years of tidy growth, two milestones propelled Shopify into the stratosphere of online retail: its initial public offering and an inexplicable decision by Amazon to essentially sell its website-building division to Shopify for a meager US$1 million.

Up until that spring, Lütke had been reticent about raising money. He flew to Silicon Valley a few times during Shopify’s early days, sleeping in hostels and biking to visit venture capital firms. Not a lot had changed since those first few fundraising attempts. When Lütke and Finkelstein, then the chief operating officer, started making the rounds on Wall Street, few prospective investors had heard of Shopify. “We just said, ‘If you bought something on the internet and it wasn’t on Amazon but the experience was good, it was a Shopify store,’ ” Lütke recalls.

When Shopify went public that May, its stock was boosted by the ineptitude of industry giants that had once dominated this corner of the enterprise software market. Yahoo Inc., which offered retailers its own tools, was distracted by internal turmoil. Another market leader, Magento, which offers open source software to build online stores, had been acquired by EBay Inc., and later spun out and bought by Adobe Inc. IBM, Salesforce, Oracle, and others offered similar services but mostly to big companies, not the small businesses that wanted to quickly and cheaply hang a shingle on the internet.

An even more critical event came a few months after the IPO. Amazon also operated a service that let independent merchants run their websites, called Webstore. Bang & Olufsen, Fruit of the Loom, and Lacoste were among the 80,000 or so companies that used it to run their online shops. If he wanted to, Bezos surely had the resources and engineering prowess to crush Shopify and steal its momentum.

But Amazon execs from that time admit that the Webstore service wasn’t very good, and its sales were dwarfed by all the rich opportunities the company was seeing in its global marketplace, where customers shop on Amazon.com, not on merchant websites. At the time, the company was also developing house brands such as Amazon Basics, and Webstore sellers had to get comfortable with the possibility that the tech giant might see their success and knock off their best products. It was a “fox-in-the-henhouse problem. Merchants were sleeping with one eye open,” says a former Amazon executive who worked on Webstore, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly about the issue.

In late 2015, in one of Bezos’ periodic purges of underachieving businesses, he agreed to close Webstore. Then, in a rare strategic mistake that’s likely to go down in the annals of corporate blunders, Amazon sent its customers to Shopify and proclaimed publicly that the Canadian company was its preferred partner for the Webstore diaspora. In exchange, Shopify agreed to offer Amazon Pay to its merchants and let them easily list their products on Amazon’s marketplace. Shopify also paid Amazon US$1 million—a financial arrangement that’s never been previously reported.

Bezos and his colleagues believed that supporting small retailers and their online shops was never going to be a large, profitable business. They were wrong—small online retailers generated about US$153 billion in sales in 2020, according to AMI Partners. “Shopify made us look like fools,” says the former Amazon executive.

For Shopify the deal paid immediate dividends. On the day it was announced, the stock price leapt so dramatically—from US$7 to US$23—that the company got requests from Finra, a U.S. regulatory authority, asking for more information on the agreement. (Finra later dropped the matter, Shopify says.) Amazon’s endorsement also gave Shopify new credibility. Only later would Amazon realize its mistake and view Shopify—and the incipient trend of brands selling directly to consumers—as a critical threat to its dominance.

Merchants, it turned out, were not only eager to pay US$30 a month for a basic Shopify subscription, they’d also happily pony up for all the extra trappings that helped them sell more stuff: for example, access to apps made by other companies for the Shopify app store, which let them send marketing texts and emails to customers or put reviews on their sites. When a large merchant uses one of those apps, Shopify takes a cut.

In 2016, Shopify introduced a lending service to help small companies that otherwise wouldn’t get the time of day from a traditional bank. The program, like one that Jack Dorsey’s Square (now called Block) had started two years earlier, lets vendors start their companies by buying inventory and hiring employees. In return, borrowers pay a percentage of their sales to Shopify until they pay off the principal and related fees. In November the company said Shopify Capital had lent a total of US$2.7 billion to merchants since inception.

Similarly, Shop Pay, a competitor to PayPal Holdings Inc. that it introduced in 2017, lets shoppers store credit cards as they go from one Shopify merchant to the next. Shopify collects up to 2.9 per cent of every sale plus 30¢ per transaction; it’s now one of the fastest-growing online payment tools in the U.S.

Mainly, though, what Amazon missed was the sheer number of entrepreneurs ready to put their business notions into action. These were self-starters such as Emma Mcilroy, who left a career at Nike Inc. in 2013 to start Wildfang, a fashion brand with a mission to “disrupt gender norms.” Before the pandemic, Mcilroy operated stores in Los Angeles, New York, and Portland, Ore., as well as an online storefront using Magento, which tended to crash during the traffic surge every holiday season. “Black Friday used to be my worst week of the year. I didn’t sleep,” she says.

In October 2020 she switched to Shopify and closed the underperforming New York store, in SoHo. Now her business is predominantly online and growing. “I talk to a lot of entrepreneurs, and if I could give them just one piece of advice, it’s that I wish I had gone to Shopify eight years earlier,” Mcilroy says. “It would have made my life so much easier.”

During the first few weeks of the pandemic, Lütke warned employees in a virtual town hall meeting about the danger to merchants like Wildfang. “Every single time that there is a crisis, the biggest losers are small and medium businesses,” he recalls saying. “They are always wiped out, because they have the least amount of adaptability.” The company’s new mission, he declared, was to help sellers survive the tumult.

Shopify did that, but now many sellers are again in distress. With supply chain problems plaguing the global economy, even the largest retailers are having trouble getting merchandise from manufacturers to customers’ homes in anything resembling a timely manner. Amazon, of course, has an advantage here: a well-honed logistics network devoted to ferrying products across oceans and among about 930 warehouses around the world, then delivering packages right to people’s doorsteps. Shopify sellers sound desperate for this kind of support. “I don’t know why Shopify hasn’t done more,” says Patrick Coddou, co-founder of 11-employee Supply Co., which operates a men’s grooming-product website. “It sure would be nice if they did something to help us compete against Amazon.”

For years, Lütke toyed with the idea of getting into the gritty business of fulfillment. In 2019 the company introduced what it called the Shopify Fulfillment Network, which connects merchants with privately owned fulfillment centers offering Amazon Prime-level reliability, as well as shippers including United Parcel Service Inc. and FedEx Corp. Shopify promised to invest US$1 billion over five years to expand the service and paid US$450 million to acquire a robotics startup in Massachusetts, 6 River Systems, that makes the same kind of robots that roam the floors of Amazon warehouses. To observers it appeared Lütke was ready to buy warehouses, employ blue-collar workers, and start moving pallets and packages around the real world.

But it hasn’t happened, and Shopify still largely leaves the last mile to its merchants. In January 2021 it hired an operations executive from Amazon named Nitin Kapoor—who left after nine months. (Kapoor declined to comment.) Lütke says logistics “is a tough nut to crack for byte companies”—meaning firms that have gotten comfortable writing software, with none of the headaches of employee injuries and high-profile union campaigns. If a ruthless, Amazon-style efficiency is required to run such a network, Lütke says, “then I don’t think we’re going to succeed. We’ll do it differently, because we don’t want to show up like this.”

It’s also true that Amazon has mastered a kind of operational efficiency Shopify never had to cultivate. Instead, Shopify executives claim improbably that rapid delivery of the kinds of boutique products its merchants sell isn’t that important to shoppers. “My guess is that is not going to hold water,” says Mark Mahaney, head of internet research at Evercore ISI. “Over time, if someone delivers you a product within a day, and someone doesn’t, you will go with the solution that gets you the product in a day. I think that will be a big challenge to Shopify.”

Back in the virtual world, Lütke has struck deals with social media companies from Pinterest to TikTok, allowing sellers to better advertise and sell things on the sites where internet users spend the most time. But sellers who advertise on social networks are getting hurt on the other end, too. With Apple changing the rules around data tracking and user privacy on iPhones, Facebook ads have become more expensive and less effective, squeezing small businesses. Because of the switch, Supply’s Coddou says, his company was unprofitable this summer for the first time in its six-year history.

Shopify could lessen the blow if it helped its merchants find customers more directly—as Amazon does with every search on its website. But here, too, Lütke has been treading carefully. While Shopify launched a search feature on its Shop app in 2021, it positions itself as a neutral broker. The way the company sees it, if a customer searches for cosmetics, and Shopify sends them to Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty website instead of, say, Kylie Cosmetics, Shopify could be facing some angry Kardashians. So its search results prioritize brands that customers have already purchased from, or lists them at random.

But if a competitor figures out how to send torrents of buyers to its sellers, and then takes over the headache of shipping once they make a sale, Shopify’s 2 million merchants could easily defect with just as much enthusiasm as they’ve flocked to it over the past decade.

One of those competitors could—once again—be Amazon. Since late 2017, former company executives say, it’s been working on a project, internally code-named Santos, that would let retailers run independent sites off Amazon. They say the division is trying to recapture the opportunity Amazon squandered when it shut down Webstore. It’s nestled within the Amazon Web Services cloud computing unit, the former domain of Bezos successor Andy Jassy, and could premiere as soon as next year. (Amazon declined to comment.)

Lütke sounds a bit fatalistic about that. “I think of Amazon as a worthy rival,” he says. “If they knock it out of the park and make it super easy to start new businesses on it, then I’m like, I actually accomplished my mission.” He says he’s up for being the underdog again—perhaps to reclaim the mantle of the rebel alliance. It’s an attitude he might need in light of a 13 per cent drop in Shopify’s stock price over the past month, as investors fret over the prospect of sluggish post-lockdown online sales and inflation. “For all the years that I’ve done Shopify, people have very consistently underestimated the size of the internet and the size of retail,” Lütke says. “It’s just very big.”

For now he’s focused on continuing to build a company untethered to any physical place, though he concedes that Shopify’s tumultuous year might’ve been easier with after-work rituals like going for drinks. “The internet hasn’t figured out how to make communities self-heal past a certain point,” he says. He also doesn’t rule out the possibility of one day reversing his position, hunkering down in new offices, and writing “a fun mea culpa.”

More pressing, though, is reconnecting with senior Shopify executives, including some he’s still never met in person. This fall he invited his management team to the Opinicon, a rustic 1880s-era hotel and resort he and McKean bought and painstakingly restored in 2015, about 80 miles from their home. During the day, the Shopify execs played laser tag. At night they talked around a bonfire. And for the first time in months, like the old days, Shopify wasn’t Everywhere, but in a more conventional location, its leadership concentrated near Ottawa, Canada.

—With Michael Tobin