Nov 23, 2022

Hunt Under Pressure as Case for Abolishing Non-Dom Status Builds

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s decision to maintain non-domiciled tax status is becoming harder to defend amid evidence that removing it would not prompt wealthy individuals to leave the country.

At a time when the Treasury is raising taxes and slashing spending to plug a hole in the public finances, allowing an estimated 70,000 people to keep avoiding tax on their overseas earnings has drawn criticism. Economists at the London School of Economics and the University of Warwick have projected that abolishing the exemption would bring in as much as £3.2 billion ($3.9 billion) in tax revenues, enough to pay the salaries of more than 90,000 nurses.

Hunt said during testimony to lawmakers on Wednesday that he has asked the Treasury to look into the potential revenue figure, but reiterated his concern that removing the special tax status could drive non-doms away.

“Non-doms pay around £8 billion of tax per year,” he told the Treasury Committee. “These are people that are highly mobile. I want to be sure that there are no dynamic effects that mean we lose more money than we gain.”

The academics at the LSE and Warwick say there is little to justify his claim. A report they published last month showed that when non-dom eligibility rules were tightened in 2017, just 0.2% of those affected left the country and those that did were paying the least tax. The Institute for Public Policy Research, a left-of-center think tank, is also calling for non-dom status to be scrapped.

“These people will always be classed as mobile, but they have kids that go to school here, they’re likely have businesses here or are entrepreneurs here, or have property,” said George Dibb, head of the center for economic justice at IPPR. “The evidence says that if we scrapped that relief, they would simply stop claiming it and just pay more tax.”

Non-doms are British residents who are not domiciled in the UK for tax purposes. Defenders of the regime say it attracts wealthy entrepreneurs, who create companies and jobs. But their preferential status is under more scrutiny than ever at a time when Britons are struggling with the worst cost-of-living crisis in memory.

The opposition Labour Party has pledged to end the exemption if it wins power. On Wednesday, Labour leader Keir Starmer and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak clashed over the issue in the House of Commons, with Starmer accusing his Conservative rival of “clobbering” working people with tax rises and presiding over a staffing crisis in the National Health Service while protecting wealthy non-doms.

For Sunak, the attack was a personal one. Earlier this year, it emerged that his wife, Akshata Murthy, had claimed non-dom status. Murthy was not required to pay tax on dividends from her stake in her father’s Indian business, Infosys. She has since committed to pay tax on foreign earnings but will remain a non-dom, which has separate inheritance tax advantages.

Read more: Will Sunak Test the Love of Britain’s Top 1%?: Therese Raphael

The exemption dates back to 1799, when it was introduced to protect colonial investments, but has survived changes in tax law.

Arun Advani, professor of economics at the University of Warwick, said it would be difficult to find data to substantiate Hunt’s argument that non-dom spending is enough to warrant maintaining the break.

“The non-dom regime costs us money, in that we aren’t getting the tax revenues from these individuals and it actively discourages people from bringing their money onshore and investing in the UK,” he said. “That can only be bad for the economy.”

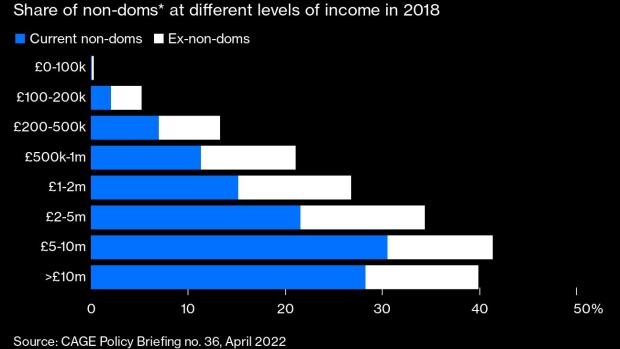

The LSE and Warwick previously published another report showing individuals using the exemption are commonly among the top earners in the UK, with one in five bankers claiming non-domiciled tax status to protect their foreign wealth, as well as highly paid individuals in the film, sports, car and oil industries.

“I wouldn’t have been too unhappy if they said, ‘Look, it’s a complicated thing to do, we’re looking at it, we’ve had three weeks in power and we can’t figure out how to do that in three weeks,”’ Advani said. “The thing I was surprised at was having nothing about it in the Budget and then Hunt coming out saying there would be negative effects from it, which they can’t really stand up based on any evidence.”

--With assistance from Therese Raphael.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.