Oct 12, 2021

IMF trims view on growth rebound as 'dangerous divergence' seen

, Bloomberg News

Supply chain disruptions are likely to persists into 2022: International Monetary Fund head

The International Monetary Fund expressed concern the global economic recovery has lost momentum and become increasingly divided, even as it stuck by its prediction for a robust rebound from the COVID-19 recession.

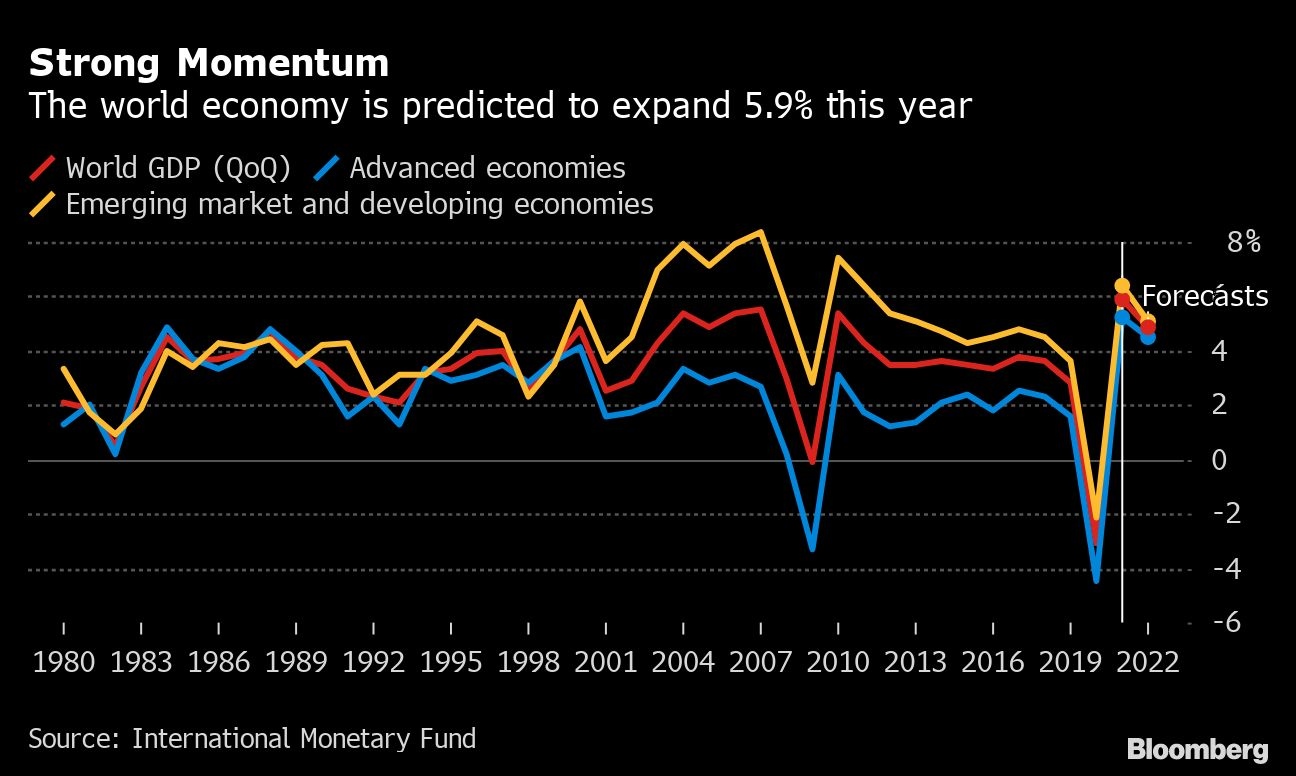

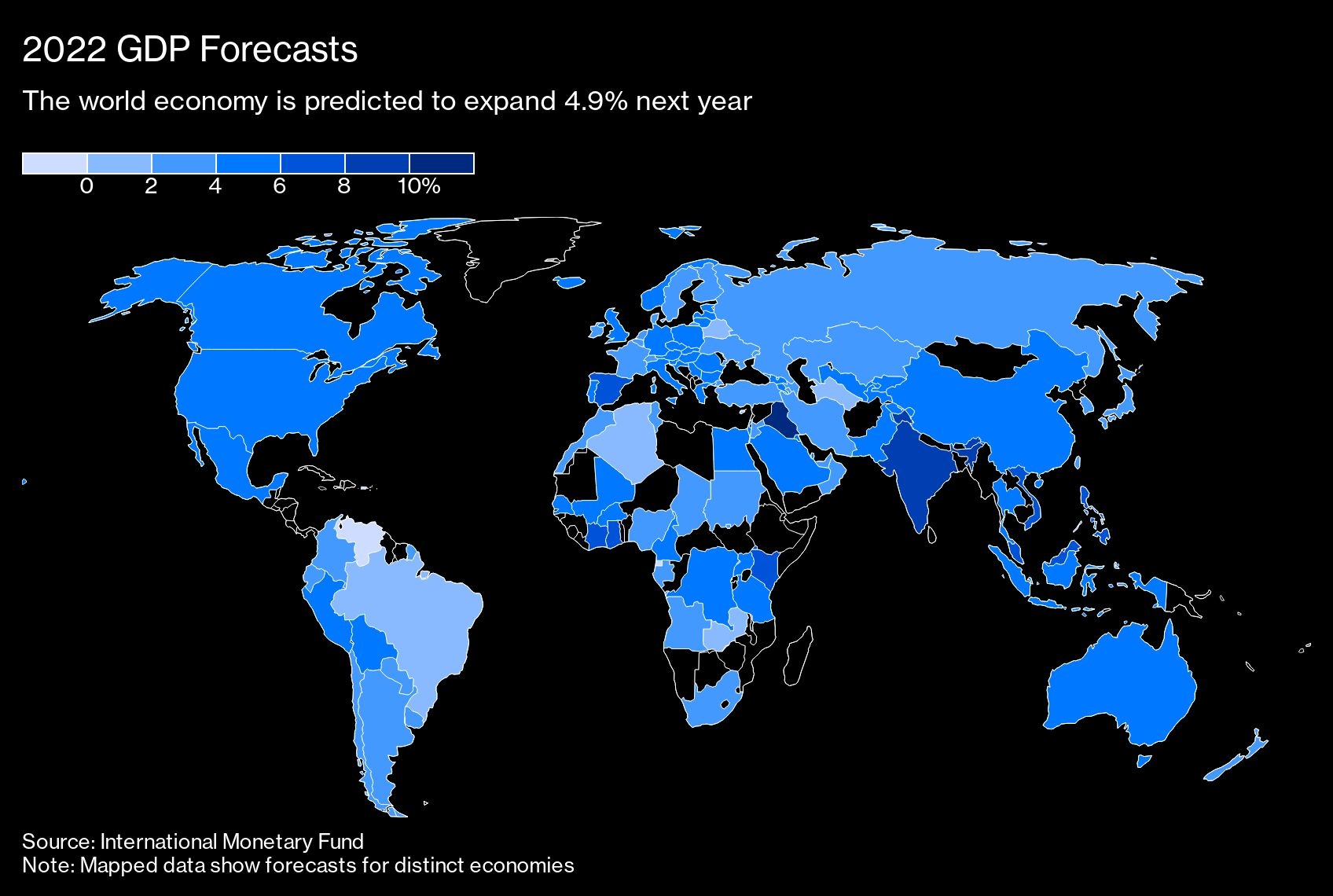

The Washington-based lender now expects output to expand 5.9 per cent worldwide this year, down 0.1 percentage point from what it anticipated in July and a bounce from the 3.1 per cent contraction of 2020, it said on Tuesday in its latest World Economic Outlook. It held the forecast for 2022 at 4.9 per cent.

The fund warned threats to growth had increased, pointing to the delta variant, strained supply chains, accelerating inflation and rising costs for food and fuel. The aggregate figure also masked large downgrades for some countries, especially low-income nations where access to vaccines remains limited.

“Overall, risks to economic prospects have increased, and policy trade-offs have become more complex,” Gita Gopinath, the fund’s director of economic research, said in the report’s introduction. “The dangerous divergence in economic prospects across countries remains a major concern.”

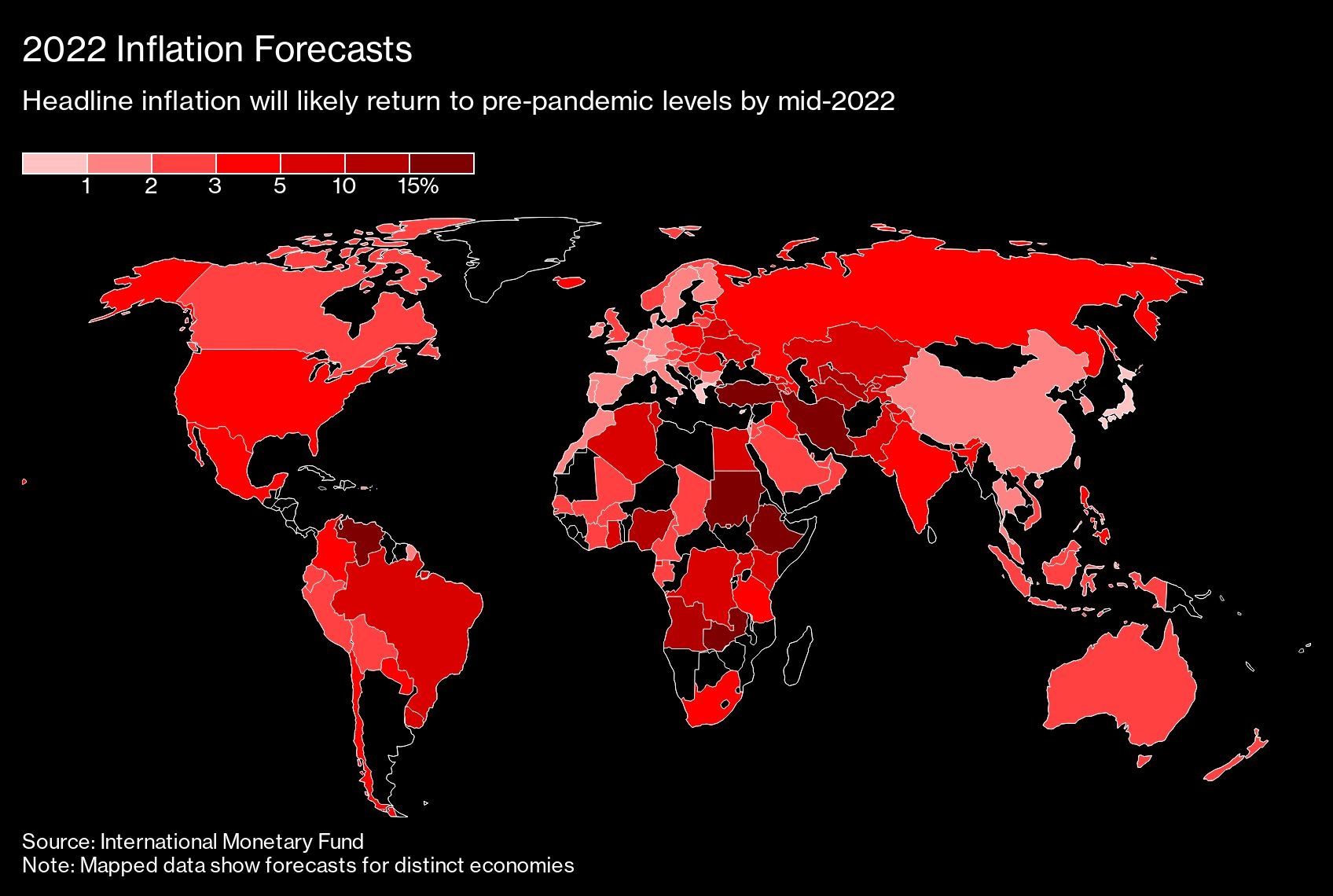

With investors increasingly worrying about the threat of stagflation, the IMF provided some comfort by saying inflation will subside to 2 per cent in advanced economies by the middle of 2022 after peaking in the final months of this year. But it bet emerging and developing economies would still see consumer prices gain 4.9 per cent next year after 5.5 per cent this year.

The fund cautioned that inflation risks are “skewed to the upside” and those for growth are “tilted to the downside.”

Among the world’s biggest economies, the IMF cut its 2021 forecast for the U.S. by a full percentage point to 6 per cent, mainly because of supply constraints, but boosted its 2022 estimate to 5.2 per cent from 4.9 per cent.

China will grow at a rate of 8 per cent this year and 5.6 per cent next, both a decline of 0.1 point from July, the fund said. It raised its projection for the euro area to 5 per cent for this year from 4.6 per cent, and kept its 2022 estimate at 4.3 per cent.

Forecasts for Japan, the U.K., Germany and Canada were all cut for this year, but lifted for 2022. Low-income countries were tipped to advance just 3 per cent this year, a slicing of 0.9 point from July.

The IMF calculated gross domestic product for advanced economies will regain its pre-pandemic level in 2022 and even exceed it by 0.9 per cent in 2024. But only two-thirds were seen regaining their earlier employment levels. In contrast, it reckoned emerging and developing markets would still undershoot their pre-pandemic forecast by 5.5 per cent in 2024.

The disparity is based chiefly in differences on vaccine access and policy support. About 60 per cent of people are vaccinated against COVID-19 in rich countries, but less than 5 per cent in low-income nations, it said. Emerging economies are also withdrawing policy support more quickly and face outsized pain from costlier food.

Central banks were told they could “generally look through” transitory inflation and avoid tightening monetary policy until they can secure more clarity, but that they should be prepared to act quickly if their economies strengthen faster than expected or if inflation expectations build.

In financial markets, the IMF said that “stretched asset valuations” meant investor sentiment could shift rapidly by adverse news on the pandemic or policy. Amid pressing concerns are the impasse over the U.S. federal debt limit and possible weakness in China’s property sector.

As a meeting of international governments on fighting climate change nears at the end of the month, the fund said “stronger concrete commitments” are needed, including tailored international carbon price floors and US$100 billion of support for developing nations. It also called again on rich countries to channel a recent bolstering of IMF resources to more needy counterparts.

Looking further out, the fund said if COVID-19 has a prolonged impact, it could reduce global GDP by US$5.3 trillion over the next five years relative to current projections. That could be offset if governments intensify efforts to equalize vaccine access.