Sep 17, 2019

In planet's fastest-warming region of Nunavut, jobs come with thaw

, Bloomberg News

5 questions with Agnico Eagle Mines CEO Sean Boyd

James Kalluk spent much of his childhood inside an igloo in Canada’s far north, close to the Arctic Circle. Building that kind of home requires temperatures low enough to freeze the region’s countless lakes, a particular consistency of snow and a long-bladed knife the Inuit call a pana.

“Today, there’s not much snow and it’s harder to make an igloo,” said Kalluk, now in his early 70s. “You may find a spot here or there that’s good, but the snow is very difficult now. It’s different.”

The loss of snow and ice are causing Canada to heat up much faster than the rest of the world—more than twice the global rate of warming, according to a national scientific assessment published in April. The farther north you go, the more accelerated the warming. The Canadian Arctic is one of the fastest-warming places, heating up at about three times the global average. That makes Canada’s northernmost Nunavut territory, a region the size of Mexico, a bellwether for the unexpected ways an altered climate transform lives and livelihoods.

In Baker Lake, Nunavut, the town of about 2,000 where Kalluk lives, almost everyone’s income is tied directly or indirectly to a nearby gold mine operated by Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd. As global warming increases access to the region’s rich natural resources, he believes the local economy will change. “In the years to come, there are going to be more houses, more development here,” Kalluk said. “More people will be able to work.”

Such growth may be welcome in Canada’s fast unfreezing north, but there are trade-offs. Kalluk worries about dust from new roads disturbing caribou that are already under siege from warmer temperatures, and about water pollution affecting fish. That environmental tug of war is the central story of Canada’s remote north. After living sustainably for thousands of years, the country’s aboriginal groups became some of the earliest to be hit by climate change. They are also in a position to benefit most from opportunities that now beckon.

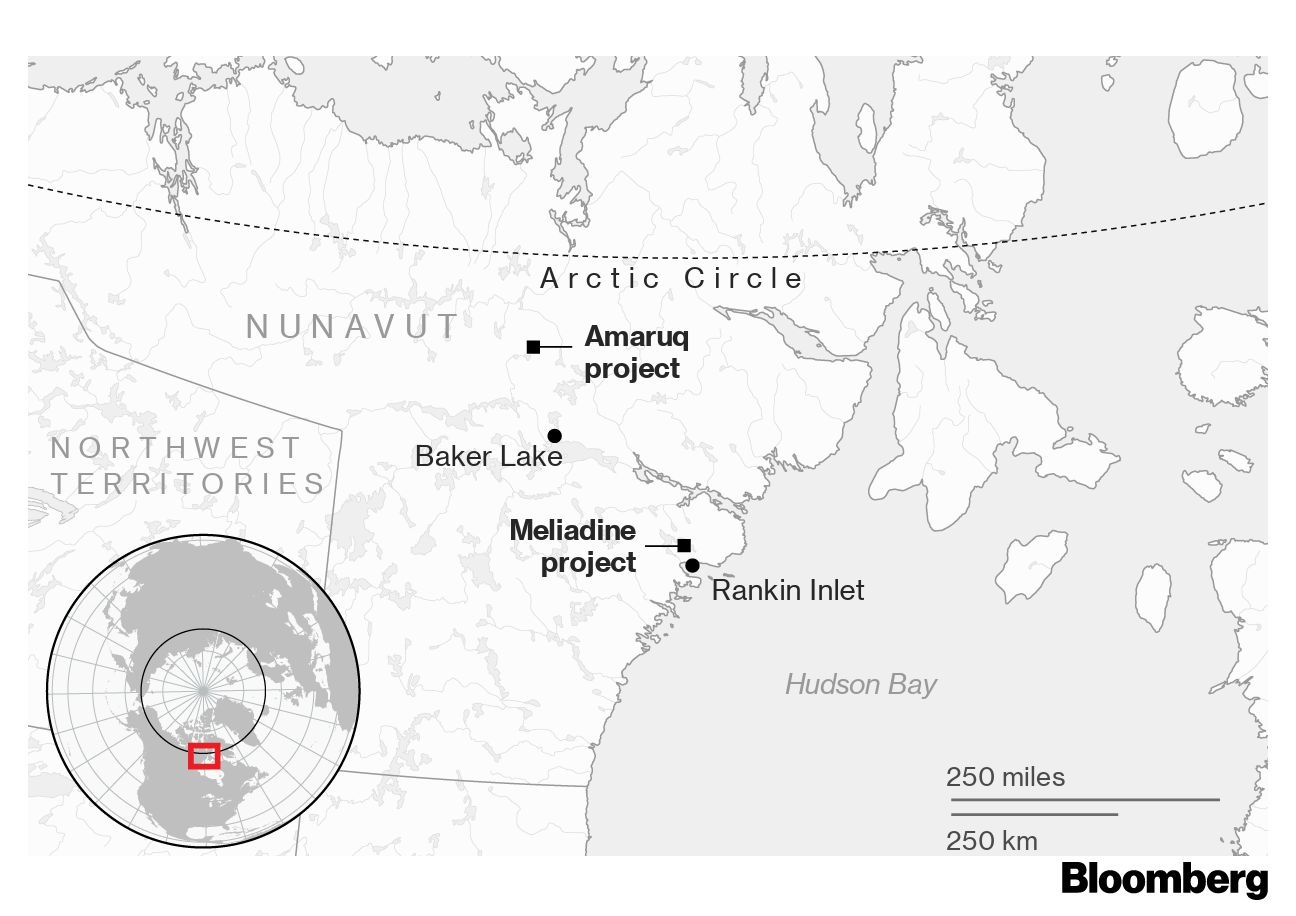

From the mosquito-sheltered comfort of his Ford Explorer, David Kakuktinniq surveys his empire through Prada sunglasses. As president of Sakku Investment Corp., he oversees 17 businesses from the town of Rankin Inlet that together get roughly half of their revenue from Agnico. The Toronto-based mining giant opened two new mines this year at a cost of $1.23 billion: Amaruq, located 175 kilometers (108 miles) north of Baker Lake; and Meliadine, about 24 kilometers from Rankin.

Kakuktinniq, 55, has never been busier. Of the 120,000 metric tons of supplies bound for the mines this year—enough to fill 6,000 shipping containers—half will be unloaded by his crews. One of his joint ventures helps provide the 120 million liters of diesel the mines will use this year.

Founded in 1957 by a now defunct nickel-and-copper mine, Rankin looks like it was built by grabbing whatever came off the barge first. Empty oil drums and shipping containers are scattered among homes and businesses. Dogs lie chained beside broken pallets, old boats and snowmobiles. The most spectacular view of the pristine waters of Hudson Bay, home to whales and arctic char, is beside the town dump. For an entrepreneur like Kakuktinniq, it’s possible to stand next to the rusty remnants of the town’s past and imagine a bright future in which longer windows of ice-free waters open the town to tourism and business.

The world’s Arctic and sub-Arctic land and waters generate US$174 billion in annual economic activity, according to a report released by the Canadian Senate in June. Canada controls 25 per cent of this circumpolar geography but accounts for less than two per cent of its economy. Rich in natural resources that have long been stranded by climate, the far north may soon benefit from increased coastal access. This will create opportunities—and potentially, headaches. U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent offer to buy Greenland from Denmark is indicative of the heightened interest in the Arctic from the world’s superpowers.

For Canadian policymakers, this underscores a need to reinforce national claims and invest in infrastructure. The government unveiled a $2 billion plan in 2017 to invest in the north, but there’s been only modest spending so far. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in a close fight for re-election on Oct. 21, recently put forward a new northern policy initiative around sovereignty and investment.

The opportunities, especially around trade, are significant. As melting ice opens up coastal areas, Canadian ports are likely to become gateways linking Asia and Europe through the Northwest Passage, bypassing the Panama and Suez canals. The Russia-controlled Northern Sea Route will be a major rival. Canada’s Port of Prince Rupert on the Pacific coast is already positioning itself to take advantage of the new routes, which it claims can shave nine days off a shipment to Rotterdam. Global warming will eventually add four to eight weeks to the unfrozen shipping season in Churchill, Manitoba, a deep-water port on Hudson Bay.

“We’re definitely looking at a future with less sea ice in the Canadian Arctic and more shipping activity,” said Chris Derksen, a climate scientist with Environment Canada who tracks the speed of warming. On the current trajectory, the Arctic will warm an additional 5 to 6 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, meaning it likely will be clear of ice in summer. If the Paris Agreement on climate is met—a longshot goal, under current trends—Derksen’s research suggests sea ice loss will continue until 2050 or 2060.

The melting ice will mean increased access to offshore oil and gas reserves, further complicating any effort to limit global greenhouse-gas emissions. Tapping inland resources may be trickier. Mining is the largest private sector employer in Canada’s Arctic, generating up to a quarter of gross domestic product across the three northern territories and accounting for one in six jobs. Miners do business here across an area bigger than India, despite limited roads, power or telecommunications infrastructure.

Mining engineers will need to contend with climate-triggered “thermokarst,” a process in which thawing permafrost makes soil slump, creating new lakes and forcing others to drain. It’s not insurmountable, but it will drive up costs. Thawing is expected to add to the feedback loops that are accelerating Arctic warming. As sea ice turns to water, for example, less heat is reflected back into the atmosphere, speeding up the thaw. The thawing permafrost, in turn, releases more carbon that traps more heat in the atmosphere.

Arctic vegetation is shifting in response to that amplified warming. Page Burt, a 73-year-old biologist in Rankin, monitors changes to blooming times and the replacement of the tundra’s low heath with taller shrubs that caribou dislike. Even with the higher wages provided by mining, caribou remain the primary food source for Inuit in the region, which means warming could increase food scarcity. The trend has been particularly devastating on Baffin Island, where the main herd has all but disappeared.

Mining is an almost inevitable employer in Rankin. Among Burt’s many jobs—her house is part of a hotel she runs—is consulting for miners, including Agnico, on environmental impacts. Her husband, John Hickes, 75, has his own connections to the mines, having served as chief negotiator between the Inuit and Agnico. Hickes, who was born in an igloo, also operates a dog-sled tourism business.

Among the most dangerous climate-related changes he’s noticed is unpredictable ice thickness, which makes hunting more dangerous. “Twenty years ago, you could ask an Inuk if a lake was suitable to cross by foot. Right now, that Inuk will tell you, ‘I don't know,’” Hickes said.

The all-weather road to Agnico’s Amaruq mining camp bisects an expanse of tundra that in late July is a multicolored tapestry of lichen, moss and wildflowers. Speed is capped at 50 kilometers an hour (30 mph) to control dust and keep the gigantic trucks from flattening wildlife. On route to the camp, 22-year-old Kaytlyn Amitnak describes the animals who live here: sand cranes and foxes, wolverine and muskox, eagles, hares and legions of ground squirrels called siksik. Twice a year, as many as 250,000 caribou migrate across the mine’s routes from Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet. The herd has closed the roads for more than 50 days so far this year.

Amitnak works as a human resources agent for the mine. Until now, she’s managed to split her “two weeks on/two weeks off” rotation between the camp and her parents’ home in Baker Lake, which she shares with her two-year-old daughter and other family members. Housing is desperately short and prohibitively expensive throughout the north, prompting Agnico to fly some two-thirds of the mining workers on charter flights from elsewhere in Canada. Amitnak recently decided to join the long-haul commuters, leaving her daughter with family so she can rent a home in Ottawa.

Living far away won’t be easy, she said, but it will provide her daughter with otherwise unattainable luxuries. She pulls up a photo of the little girl on her phone, dressed in traditional Inuit clothing and trying to bore a fishing hole in the ice with a chisel—or “tuuq”—so big she can barely hold it. Amitnak recently bought her a trampoline with her mine wages and is looking forward to an upcoming heavy metal concert in Toronto.

“It’s almost like living in two worlds,” she said.

Flying more workers longer distances drives up Agnico’s operating costs. If its deposits weren't so rich and the company weren’t large, the cost of dealing with a long list of geographic hurdles would swamp the new gold mines. Fuel is the big one: Diesel is dirty and expensive—and hit by Canada’s carbon tax.

Agnico says it would like to cut emissions, but there’s no viable alternative. Earlier this year, the company submitted a proposal to supplement diesel with renewable power purchased from the Inuit, but the federal government declined to subsidize the construction of a wind farm. The miner has also spent $200 million to build 200 kilometers of gravel road from Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet to its two new camps, making it the largest owner and operator of roads in Nunavut.

Agnico Chief Executive Officer Sean Boyd hopes the drive to assert Canada’s Arctic sovereignty will prompt the government to ramp up investment. Warmer temperatures could help his company in other ways. If Hudson Bay remains ice-free for longer, Agnico might be able to ship in cheaper, cleaner liquefied natural gas. Climate change could relieve some expensive problems associated with extreme cold: When temperatures plunge into the -30s or -40s Celsius, shovel teeth break, idled engines blow and saltwater brine needs to be pumped into drill holes to stop them from freezing.

“A big part of our job is water management,” said Tom Thomson, 41, environmental coordinator for Agnico’s operations outside Baker Lake. The miner is already using “adaptive management” techniques in anticipation of impacts from global warming—securing pillars directly into bedrock, for instance, or rethinking the ways it stores and monitors mine waste to account for thawing.

Back in Rankin Inlet, David Kakuktinniq threads his car through stacks of shipping containers fresh off the barge. Pulling into an area filled with heavy equipment, he stops in front of a line of shiny yellow tractors. Until three years ago, Kakuktinniq’s crews used these to haul sleds of fuel, but he parked them when the ice became too unpredictable. “It’s just too risky,” he said.

It’s not the only change he’s noticed as the region thaws. Houses in town that were built with steel piles socketed into permafrost are starting to tilt as the ground shifts beneath them.

“It’s changed, but it’s OK,” said Kakuktinniq, revealing what might just become the entrepreneur’s 18th venture. “We’ll create a business that fixes houses on piles.”

—With assistance by Eric Roston, Ashley Robinson and Natalie Obiko Pearson

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 220 news outlets to highlight climate change.