US Mortgage Rates Surge to Highest Since November, Hitting 7.1%

Mortgage rates in the US climbed past 7% for the first time this year.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Mortgage rates in the US climbed past 7% for the first time this year.

Mortgage shopping isn’t getting much easier these days.

Sales of previously-owned homes in the US fell in March from a one-year high, underscoring the lingering impact of high mortgage rates and elevated prices.

Blackstone Inc. collected more fees from big retail funds and credit strategies during the first quarter, compensating for the slower pace of deal exits.

Ken Griffin’s Citadel and Citadel Securities will move their London base to a new office tower on the edge of the City of London, a major expansion of their space in the latest sign of the firm’s growing heft.

Dec 18, 2018

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Why do you call them shadow banks? That’s a criticism I’ve heard often since I started chronicling the troubled world of India’s nonbank finance companies following the high-profile bust of infrastructure lender IL&FS Group in early September.

Some readers saw the characterization as an attempt to equate India’s pedigreed financiers of mortgages and consumer loans with China’s peer-to-peer lenders and trust companies, which saw scorching growth but are now gasping for survival. Meanwhile, India’s Housing Development Finance Corp. and Bajaj Finance Ltd. boast price-to-book ratios of almost 4 and more than 8 respectively,

Still, “shadow lending” is a useful catchall for firms and financial instruments that, just like banks, turn shorter-term liabilities into longer-term assets. But unlike banks, they don’t have access to liquidity from the central bank. They borrow wholesale. When they take deposits, customers don’t enjoy the protection of deposit insurance. In those two key respects, India’s nonbank finance firms fit the International Monetary Fund’s description of shadow banking.

India’s financing arrangements are far more rudimentary than what Paul McCulley, formerly of Pacific Investment Management Co., had in mind when he warned of a “run on the shadow banking system” at the 2007 Jackson Hole conference. McCulley was referring to the opaque Wall Street world of asset-backed commercial paper; structured investment vehicles; subprime residential mortgage-backed securities; and collateralized debt obligations.

The universe of more than 11,000 Indian shadow lenders draws its sustenance from formal banks, as well as from companies and individuals looking to deploy short-term surpluses. As yield-seeking capital comes into mutual funds, their managers buy commercial paper issued by operating finance companies (OpCo) as well as subscribe to bonds issued by the finance firms’ holding companies (HoldCo). The OpCo lends to home buyers, small businesses, and students as well as property developers, while the HoldCo brings in the funds borrowed from mutual funds as equity in OpCo. The minimum capital requirement of 15 percent of risk-weighted assets is easily met even as shadow lenders’ balance sheets expand by 20 percent or more.

The shadow lenders, pumping out 30 percent of all new credit over the past three years, are the reason why the Indian economy isn’t withering for lack of finance, despite a serious banking crisis: Eleven out of 21 state-run banks are languishing in a regulatory prison. (The central bank wants them to boost their depleted equity before they can meaningfully expand their loan books again.) New skyscrapers are coming up, and small businesses are using loans against property to meet their working-capital needs. Traders are getting finance by pledging warehouse receipts.

This is where a comparison with China is useful. At 14 percent of GDP, India’s shadow-banking universe is much smaller than the 70 percent ratio in the People’s Republic, as Moody’s Investors Service notes. But while Beijing has successfully shrunk the industry from 87 percent of GDP at the end of 2016 — a drop of 17 percentage points — New Delhi can’t afford the nonbank lenders to stumble even accidentally. If they retreat, capital-constrained local banks won’t be able to take up the slack. Nor will an indebted Indian government be able to offset a resulting economic slowdown, the rating company said.

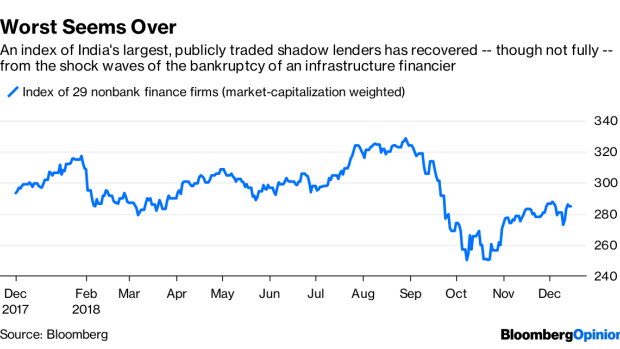

That’s why during the crisis of confidence triggered by IL&FS’s $12.8 billion bankruptcy, emergency liquidity support for shadow-banking became a contested issue between the government and the central bank, which wasn’t keen to deploy its balance sheet to take on private credit risk. The worst of the September stress has eased, but concerns about elevated funding costs remain. “Weaker balance sheets are going to fall off,” Saurabh Chawla, the outgoing chief financial officer of DLF Ltd., India’s largest listed property developer, told Bloomberg News.

Now that New Delhi has replaced an independent-minded technocrat at the Reserve Bank of India with a former finance-ministry bureaucrat, it’s reasonable to expect that shadow banks will be encouraged to expand again. The RBI is finicky about who gets a banking license, but even owners of bankrupt power firms are welcome to write home loans. Nor do the markets discriminate. Mutual funds are happy to lend based on inflated credit ratings, as became evident when IL&FS blew up. As that crisis fades from memory, excesses will rebuild, and asset-quality will deteriorate.

Will New Delhi be prepared to pull the rug from under the nonbank lenders if they push things too far? On that count, hold no hope. China’s shadow banking may be a lot bigger than India’s, but India’s is already too big to fail.

To contact the author of this story: Andy Mukherjee at amukherjee@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.