Apr 22, 2021

Inflation forces Bank of Canada's hand ahead of Fed and ECB

, Bloomberg News

McCreath: Bank of Canada lays out path to higher rates

The Bank of Canada sent out a warning to investors this week that inflation still matters.

In a surprise move, it accelerated the timetable for a possible interest-rate increase and began paring back its bond purchases on Wednesday. That made Canada the first major economy to signal its intent to reduce emergency levels of monetary stimulus.

It’s a turn in policy by Governor Tiff Macklem that shows there’s a limit to how much he’s willing to test the upper boundaries of inflation, with new forecasts showing the central bank expects the biggest persistent overshoot of its 2 per cent target in at least two decades. The question is whether Canada’s situation is unique, or foreshadowing the start of a global exit from stimulus.

“Canada does give you a flavor of what happens when your trajectory is stronger than anticipated,” said Su-Lin Ong, head of Australian economic and fixed-income strategy at Royal Bank of Canada in Sydney.

While the Canadian dollar jumped the most since June on Wednesday, the Bank of Canada’s big move didn’t cause much of a ripple effect in global markets. The MSCI benchmark for global stocks is trading within 1 per cent of a record high. Ten-year U.S. Treasury yields have fallen below 1.6 per cent, from 1.74 per cent at the end of March, as investors pare expectations that the Federal Reserve will raise rates soon.

‘Distinguishing Factors’

Counterparts elsewhere, meanwhile, are resisting. At a decision Thursday, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said the institution isn’t discussing the phasing out of its emergency bond buying, while the Federal Reserve has long been adamant it won’t scale back the pace of its US$120 billion-a-month bond purchases until it sees “substantial further progress” on employment and inflation.

“Central banks of small economies can sometimes be canaries in the coal mine,” Krishna Guha, vice chairman at Washington-based Evercore ISI, said in a report to investors. “But while there are some elements of this decision that have an obvious read-across to other central banks, there are also distinguishing factors that caution against naive extrapolation.”

Some analysts don’t even see the Canadian central bank taking a dramatically more aggressive policy stance, even after Wednesday’s move. At a press conference after the decision, Macklem emphasized the central bank’s commitment is not to raise interest rates before the economy fully recovers, and that any future hike would reflect economic conditions at the time.

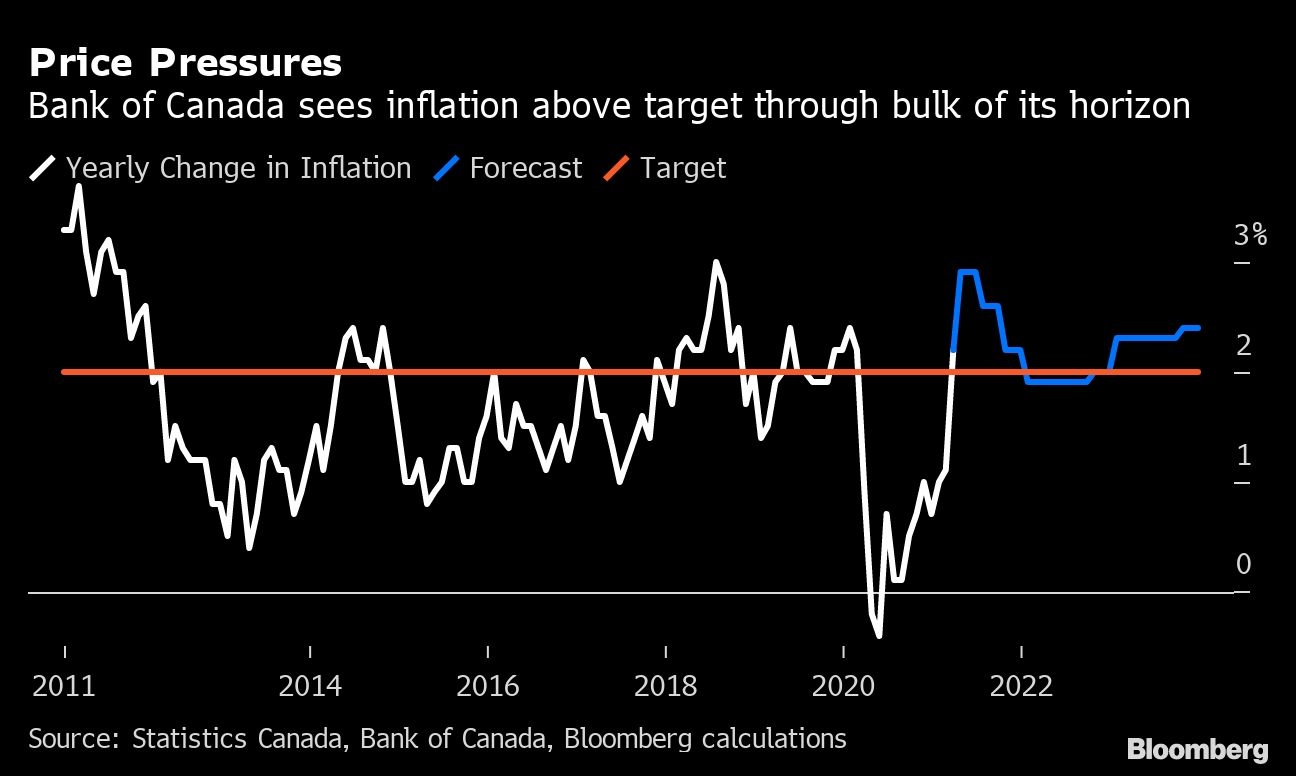

Price Pressures

Macklem is right-sizing one of the more aggressive quantitative easing programs relative to the size of its bond market, in an economy also being supported by massive fiscal stimulus. The Bank of Canada owns more than 40 per cent of outstanding federal government bonds, potentially distorting the market.

“Canada is different. The amount of the bonds they are buying is huge,” Steve Englander, head of global G-10 FX research at Standard Chartered Bank in New York, said by phone. “The Fed doesn’t have that issue.”

The economic fundamentals are also pretty solid. Canada’s jobs market has recouped 90 per cent of losses during the pandemic, versus just over 60 per cent of U.S. losses made up so far. Canada’s red-hot housing market is another worry.

“The situation is sufficiently unique in Canada that I’m not sure it applies to the Fed, or ECB,” Jean-Francois Perrault, chief economist at Bank of Nova Scotia, said by phone. “Our labor market basically is back to where it was.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“The Bank of Canada brought forward when it expects the economy’s excess slack to be absorbed, but the accompanying Monetary Policy Report includes discussion of several factors that could soften the need to pull forward a rate hike into 2022. We continue to think a rate move is likely to be delayed into the first quarter of 2023.”

--Andrew Husby, economist

Perhaps more consequential, the Bank of Canada’s mandate is narrow -- focused on a 2 per cent inflation target, with some flexibility over timing. Consumer price gains are expected to be at or above that mark for more than 70 per cent of its forecast horizon, according to Bloomberg calculations on Bank of Canada data. The central bank sees inflation at 2.4 per cent in the final quarter of 2023, a rare divergence from target at the close of its forecasts.

Macklem justified his tolerance for above-target inflation this week by citing the central bank’s decision not to preemptively raise rates until a full recovery. It’s a policy that’s paralleled in the U.S.

But the Fed is juggling a number of objectives. These include growing concerns about racial equity that suggest it’s waiting for the headline jobless number to drop even below estimates of full employment.

A more accommodative approach was formalized in a policy review last year that now allows the Fed to explicitly overshoot 2 per cent inflation moderately for some time. It’s an option the Bank of Canada is considering as it completes its own mandate renewal later this year.

--With assistance from Michael Heath, Alister Bull and Erik Hertzberg.