Housing starts down 7% in March from February: CMHC

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. says the annual pace of housing starts in March declined seven per cent compared with February.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. says the annual pace of housing starts in March declined seven per cent compared with February.

A rebound at John Paulson’s family office boosted returns last year but it still wasn’t enough to keep the billionaire investor from having to play catch-up.

New home construction in the US slowed last month as a leveling off in interest rates has given way to a lull in housing demand and caution among builders.

Citadel founder Ken Griffin’s efforts to build a 62-story office tower on Manhattan’s Park Avenue have taken a significant step forward.

As the US economy hums along month after month, minting hundreds of thousands of new jobs and confounding experts who had warned of an imminent downturn, some on Wall Street are starting to entertain a fringe economic theory.

Dec 16, 2021

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

High inflation rates aren’t bad news for everyone. They can be helpful for debtors -- which in today’s world economy means almost everybody.

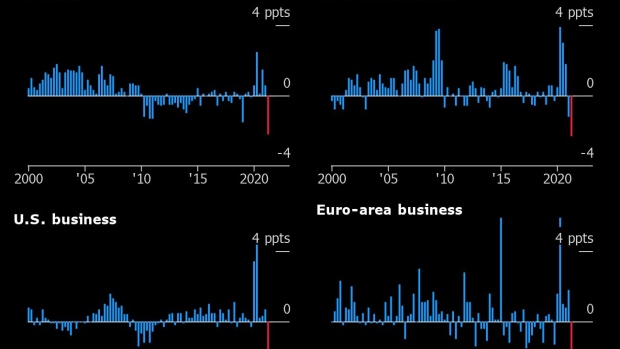

In the second quarter of this year, measures of household and business debt as a share of economic output saw some of the steepest drops on record in several advanced economies, according to data published last week by the Bank for International Settlements.

That’s not because consumers and companies were borrowing less, in dollars, euros or pounds -- which is what happened in the drawn-out recession that followed the 2008 crisis. In fact, they’re borrowing more. It’s just that the combination of rapid post-lockdown growth and accelerating inflation meant that their liabilities shrank by comparison with the overall size of the economy as it’s measured in those same currencies.

To be sure, declines over one or two quarters don’t make much of a dent in overall debt burdens that soared earlier in the pandemic, as central banks extended credit safety-nets to business, while mortgage lending took off amid a housing boom.

Almost every kind of debt remains larger, as a share of the economy, than it was at the start of 2020, and well above historical norms.

The U.S. corporate borrowing spree, in particular, has raised some red flags -- and while companies overall are posting fat pandemic profits, aggregate numbers don’t tell the whole story: the businesses with debt problems may not be the ones that are raking in the cash. Higher interest rates -- the coming antidote to inflation -- will make debt-servicing harder.

Still, the data are a reminder that rising prices can have some beneficial side effects -- which is one reason why central banks spent the decade before Covid-19 trying to engineer higher inflation rates, even if they’re now pivoting in the opposite direction after a bigger-than-expected spike.

What About Governments?

The BIS numbers show a drop in ratios of government debt to GDP in the most recent quarter, too. That’s been the fastest-growing type of borrowing in the pandemic, just as it’s been ever since the 2008 crash.

Public debt may be less of a worry though, because in the developed world it’s generally proved to be less combustible than the private kind.

Debt crises in advanced economies over recent decades haven’t been the result of governments borrowing too much in their own currencies, liabilities they can always meet. Instead, they’ve been triggered by high levels of private debt -- like the bursting of Japan’s corporate credit bubble in the 1990s, and the U.S. mortgage meltdown the following decade -- or public debt in countries that don’t issue their own currency, such as Greece.

With most economists expecting relatively high rates of inflation, and strong growth in real output, to continue into 2022, the erosion of debt burdens may have further to go.

But in the U.S., at least. it will require an extended period of rising pay for workers, especially lower down the income ladder, to reflate the economy in a way that can ease debt burdens for households, says Daniel Alpert, a founding managing partner at Westwood Capital LLC. He’s skeptical that will happen.

Alpert, the author of a recent paper titled “Inflation in the 21st Century,” says high debt levels for ordinary Americans are the result of decades in which income shifted from labor to capital. “What’s going to drive the longer, sustained type of inflation you really need to lessen the burden on households?” he says. “The answer is sustained wage improvement, which I don’t think we’re going to get.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.