Jun 23, 2021

Inflation overshoot has BoC weighing mandate tweaks

, Bloomberg News

CPP Investments CEO doesn't see 'risk of runaway inflation' in the long term

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem is in the final stages of a mandate review that could see him request more authority from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government to run the economy hot.

The central bank’s five-year inflation targeting mandate is up for renewal this year, with few signs a major overhaul is in the works.

But Macklem might lean toward design and communication changes to the 2 per cent target, perhaps by focusing on labor-market metrics or putting more emphasis on the Bank of Canada’s allowable range for inflation. That could give him some more flexibility to address under-performance in the economy at a time when other central banks are doing the same.

The Federal Reserve adopted so-called average inflation targeting last year -- on top of its dual maximum employment mandate -- that allows the U.S. central bank to overshoot its 2 per cent target, though developments last week suggest there are limits to its tolerance. The European Central Bank is also in the midst of potentially its biggest policy overhaul in almost two decades.

Options the Bank of Canada is likely considering in its review include the following:

STATUS QUO

Canada’s central bank has been studying the possibility of larger wholesale mandate changes to make its policies more suitable for the current weak-growth era, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only sharpened that focus. But Macklem could argue the existing mandate already provides the flexibility needed.

Since the 1990s, the bank has been narrowly focused on a single objective: to keep prices stable. The goal has been to keep inflation within a range of 1 per cent to 3 per cent as much as possible. Operationally, that’s meant aiming for a 2 per cent target over the central bank’s forecast horizon, a period of about two years.

There’s plenty of leeway, though. The bank has scope to delay the return of inflation to target beyond the two-year span. Macklem and his officials also have discretion to put more weight on certain risks over others. In a world just emerging from an unprecedented crisis, for example, tightening too quickly is seen as a bigger policy risk than having inflation slightly faster than target.

The Bank of Canada is drawing on some of that flexibility right now to keep emergency levels of stimulus in place.

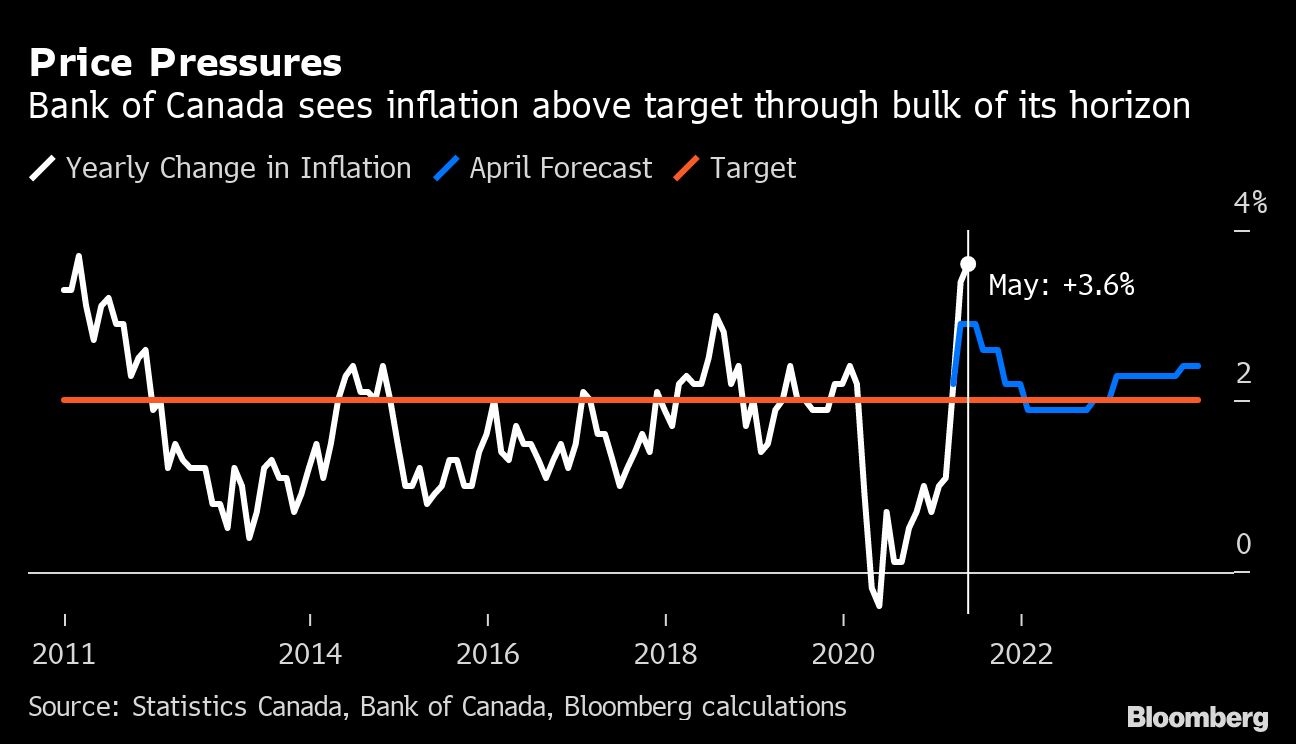

In its latest forecasts released in April, officials projected inflation at 2.4 per cent in the final quarter of 2023, a rare divergence from target almost three years into the future. Macklem has also begun hinting about using the central bank’s “inflation-control range” of 1 per cent to 3 per cent as a policy tool, a departure from recent practice.

But the explanation risks becoming a bit obscure as Macklem tests his mandate’s limits.

For one, there’s no guidance yet on when the bank actually expects inflation to return to target. Meanwhile, inflation that’s risen to 3.6 per cent -- the highest in a decade -- coupled with the Bank of Canada’s quantitative easing program have become a political issue, with the main opposition Conservative Party already questioning the governor’s actions.

For political cover alone, Macklem might want to codify some of the adjustments he’s already put into place.

“He may want some more formal flexibility to do what he seems to want to do right now,” said Don Drummond, a former chief economist at Toronto-Dominion Bank who worked in senior positions at the finance department when inflation targeting was implemented in the early 1990s.

NEW LANGUAGE

Macklem could incorporate some new language that’s already central to his policy narrative. Since last July, for example, bank officials have been promising not to raise borrowing costs until inflation has “sustainably” returned to target. By sustainably, officials mean inflation above 2 per cent is no longer sufficient to trigger a response; the economy will also need to have relatively tight labor-market conditions.

Deputy Governor Tim Lane said this month the differences between the Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada mandates diminish once that nuance is taken into account.

“Even though we don’t have a mandate for maximum employment, at the same time we do take account of labor market conditions very much in making our assessment of when inflation is sustainably at target,” Lane said at a June 10 press conference.

LABOR MARKET

Another option is to add explicit labor-market metrics or language into the mandate.

The Bank of Canada is already putting increased emphasis on a “full” labor-market recovery as it considers when to scale back emergency levels of stimulus, and is focusing in particular on the pandemic’s unequal impact on groups such women and youth.

“The bigger question for me is are they going to put more emphasis on the labor market, because we are hearing them talk about it more than in the past,” Beata Caranci, chief economist at Toronto-Dominion Bank, said by phone.

Asked about the inflation mandate renewal at a June 16 press conference, Macklem said consultations with the public show “a consensus employment should be a part of the thinking, the framework and this is something that we have taken to heart.”

The Bank of Canada could prioritize certain indicators, like the participation rate, or start forecasting unemployment like the U.S. to emphasize the importance of the jobs market, Caranci said.

THE BAND

At a mandate renewal exactly two decades ago, the Bank of Canada took steps to demote the importance of the inflation range and put more weight on the 2 per cent target.

Benjamin Reitzes, a rates and macro strategist at BMO Capital Markets, believes that pendulum could swing back, which would give the central bank more flexibility to overshoot at times.

“It really is just a subtle change but provides a bit more flexibility to run hot for a bit long if needed,” Reitzes said by email. “The language can be a bit tricky but should be very doable.”