Oct 18, 2018

Inside Facebook's 'War Room' that aims to combat fake news

, Bloomberg News

As polls closed in Brazil on Oct. 7, Facebook Inc. data scientists, engineers and policy experts gathered in a new space in the company’s Menlo Park, California, headquarters called the War Room. As they monitored trends on the company’s sites -- like articles that were going viral and spikes in political-ad spending -- they noticed a suspicious surge in user reports of hate speech.

The data scientists in the room told the policy experts that the malicious posts were targeting people in a certain area of Brazil, the poorer Northeast -- the only region carried by the leftist presidential candidate. The policy folks determined that what the posts were saying was against Facebook’s rules on inciting violence. And an operations representative made sure that all of that content was removed.

The company, the world’s largest social network, says that by having different experts in this one room, representing their larger teams and coordinating the response together, they were able to address in two hours what otherwise might have taken several days -- time that’s too valuable to waste during a critical election.

“We were all delighted to see how efficient we were able to be, from point of detection to point of action,’’ Samidh Chakrabarti, Facebook’s head of civic engagement, said Wednesday in a meeting with reporters.

Delight is not a sentiment that people in Brazil necessarily share. Despite Facebook’s stronger and more organized coordination of its effort to improve election-related content, Latin America’s largest country was still overrun with misinformation, much of it distributed via Facebook services. False information that was thwarted on Facebook’s main site by the company’s network of fact-checkers was still able to thrive on its WhatsApp messaging app, which is encrypted and virtually impossible to monitor.

(David Paul Morris/Bloomberg)

Pablo Ortellado, a professor of public policy at the University of Sao Paulo who has studied fake news, said Facebook has made good strides, but isn’t addressing the full scale of the problem. And he thinks the company’s efforts still won’t be enough to tame WhatsApp, where Facebook doesn’t have visibility into exactly what’s being shared.

“All the malicious stuff of the campaigns went through WhatsApp, that’s the problem,” he said in an interview. “Really, that was one of the disasters of this election.”

Facebook has made some improvements, especially by deleting spam accounts on WhatsApp and labeling links that have been forwarded, Chakrabarti said. Still, some of the most popular election-related stories have contained false information.

A WhatsApp representative said the app is working on education campaigns to help users understand what stories might be credible and recently lowered the limit for how many people can receive a message, to 20 from 256, which may help limit virality.

Even if it’s not a full solution, the War Room is symbolic of Facebook’s work to assuage public concern about the fake accounts, misinformation and foreign interference that cloud discussion about elections on its site. After the U.S. election in 2016, Facebook initially dismissed the idea that fake news on its site could have played a role in the outcome. But the company started to work more diligently on the problem after finding in 2017 that Russia ran a coordinated misinformation campaign to stoke discord, using stolen and fake identities. Russia’s effort reached more than 150 million people on Facebook and photo-sharing app Instagram. Since then, Facebook has found similar campaigns run in the U.S. by Iran, and even by domestic actors.

Ahead of Brazil’s runoff election Oct. 28, when far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro faces leftist Fernando Haddad, the company will again fly in its Portuguese-language experts from around the world to help. They’ll sit with about 20 other employees in a large conference room where they can view the election from Facebook’s perspective.

The room, labeled “WAR ROOM” in red block letters on a sign out front, is one of the few work spaces in the company’s headquarters with privacy. Black construction paper prevents other employees from seeing through the glass door. A few feet inside, on the wall, is a map of Brazil, with markers on several areas the task force is evaluating. On another wall, above large screens monitoring trends, is the Brazilian flag. Across from that is the American flag -- a reminder that whatever happens in Brazil will inform how Facebook handles the U.S. midterms a few days later.

(David Paul Morris/Bloomberg)

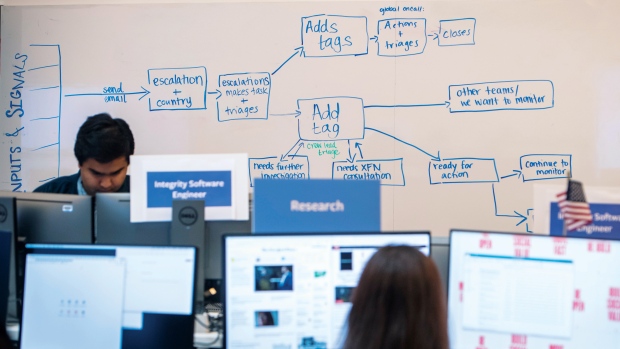

“We’ve been doing extensive scenario planning,’’ running drills on problems both real and imagined, Chakrabarti said. Engineers have built dashboards that measure election-related activity that could be threatening, such as the rate of foreign political content coming into a country having an election, or user reports of misinformation about voting. Any unusual spikes will set off alarms and bring an item onto a main to-do list called the “situation board.”

To augment the information it can glean from Facebook and Instagram, the company uses its CrowdTangle tool to monitor news trends on Twitter and online discussion forum Reddit. It also asks for information from regional government officials on any voting irregularities to which Facebook may be contributing.

“People say they’ve been so slow to respond, but shifting all those engineers, policy people and product managers into a central space to all focus on something like the threat to democracy is actually really significant,’’ said Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft, which coordinated fact-checking with Facebook during the most recent elections in France and the U.K.

Facebook has long been hesitant to mark news as true or false, except through third-party fact checkers like First Draft, because it doesn’t want to be the arbiter of truth on the internet. And even those third parties are only helping down-rank what is specifically false. Wardle says Facebook doesn’t yet address the murkier part of the problem -- the incendiary content that may be partly true or lack proper context.

The War Room shows Facebook’s commitment to looking at the problem a different way, the company says. Instead of directly assessing individual pieces of content flowing through the site, they can evaluate trends of user behavior that may raise concerns, such as fake accounts and foreign election-related content.

Still, Facebook’s advances remain confined to areas like the news feed and Instagram. Ahead of U.S. midterm elections in November, the company has been slower to tackle spaces like Facebook groups, where users can share in smaller communities, much like in WhatsApp, First Draft’s Wardle said.

“We’re seeing some pretty nasty stuff around the midterms, but there’s just really no discussion about how this is shaping up in darker or closed spaces, which I think is a shame,” Wardle said. “By 2020, if we’re really serious about understanding this information in the lead-up to the next presidential election, I hope that we’ve got a clearer sense of what we need to learn from places like Brazil.”

--With assistance from Kariny Leal