Nov 8, 2021

Inside the Succession-style drama at Rogers Communications

, Bloomberg News

Rogers has been underforming relative to other Canadian stocks since spring 2019: Colin Cieszynski

It was the deal of a generation. Joe Natale, chief executive officer of Rogers Communications Inc., Canada’s biggest wireless operator, struck a US$16 billion agreement in March to take over rival Shaw Communications Inc. The long-anticipated union of two prominent business clans marked the birth of a new national champion. Flying into Calgary one bleak day last winter, Natale met his counterpart in an airport hangar to thrash out the key terms of the union, one that had been coveted for decades by the company’s late founder, Ted Rogers. Risky, debt-laden, yet potentially transformative, it was the kind of deal the swashbuckling titan would’ve loved. Little did Natale know that Ted Rogers’s only son at that moment was already maneuvering to oust him.

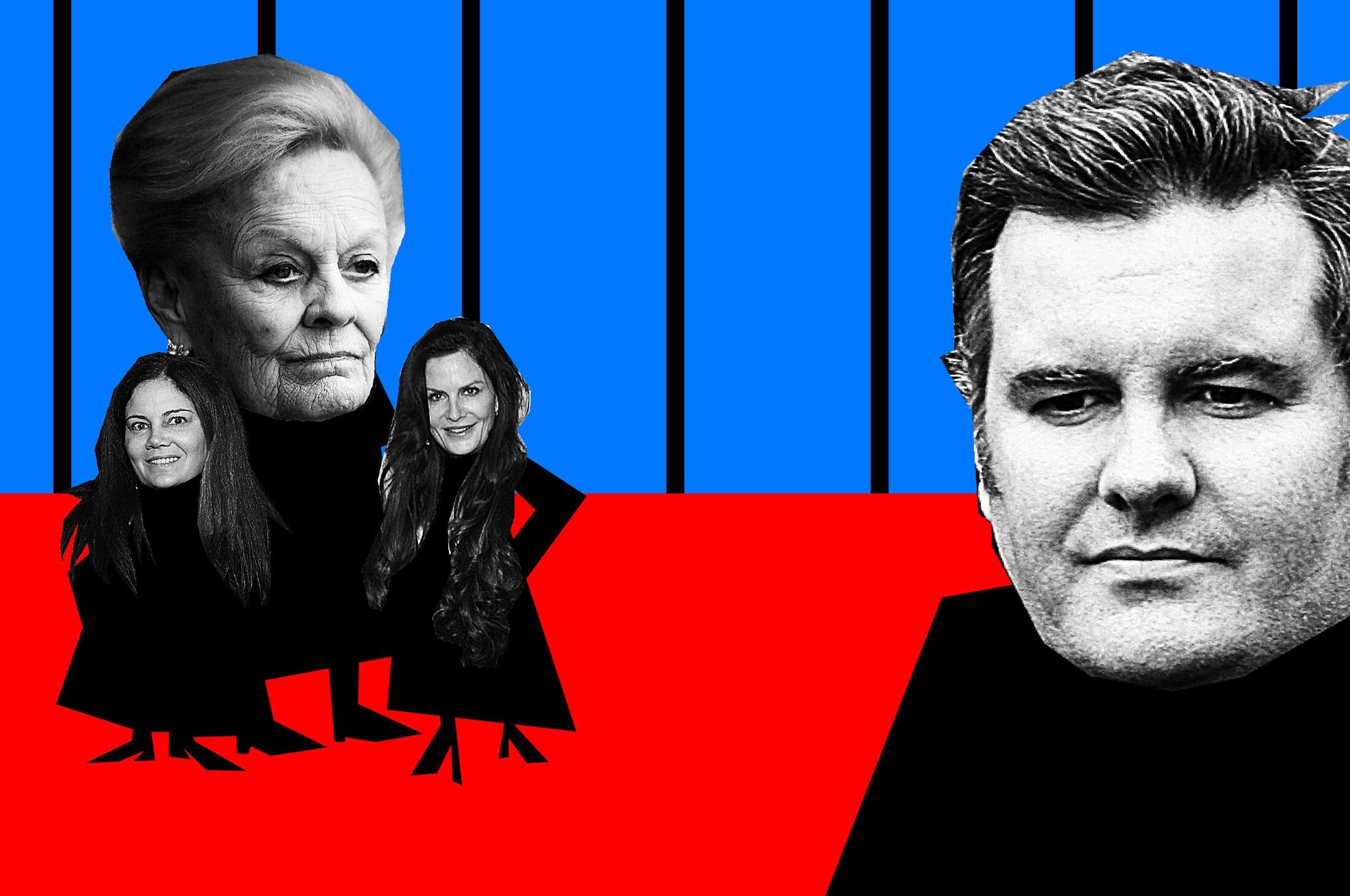

Over the next six months, Edward Rogers, who chaired both the board and the family trust controlling the company, ramped up efforts to undermine the CEO—planting doubt about Natale’s ability to navigate the Shaw deal among his family, including with his 82-year-old mother, Loretta Rogers. He pushed for a management shake-up that would seal his power over the US$24 billion Toronto-based company. His family pushed back.

The campaign reached its zenith in the fall when Edward, 52, sought to unilaterally remove Natale as CEO and replace him with his own hand-picked successor, Tony Staffieri. The move triggered a family feud that engulfed the telecom giant in chaos. Edward claimed to chair a new board that backed his moves. The company—joined by Loretta and Edward’s two younger sisters, Melinda Rogers-Hixon and Martha Rogers—sided with the original board opposing Natale’s exit. For almost two weeks, no one knew who controlled one of Canada’s biggest publicly traded companies.

Canada’s staid business world isn’t typically a source of entertainment. This time it was a blockbuster, as a long-stewing internecine rivalry among the famed Rogers family, whose fortune is estimated at more than US$10 billion by the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, spilled into public view. “LOL,” tweeted Martha Rogers in response to an Oct. 25 column headlined “Rogers Chairman Fires Board for Firing Him for Firing CEO” by Bloomberg Opinion’s Matt Levine.

British Columbia’s top court ended the uncertainty on Friday, legitimizing the new board stacked with Edward’s allies. The decision paves the way for Edward to resume plans to replace the company’s CEO, now that the company said late Sunday it won't seek an appeal.

“I take no joy in the decision or the events of past weeks,” Edward said in a statement after the ruling, adding that he hoped to resolve the family differences privately. “Our focus must be on the business, a return to stability, and closing our transformational merger with Shaw Communications.”

While the spectacle has transfixed Canada, it’s also thrust the nation’s largest wireless operator into deep uncertainty at a critical moment. The company is hoping to close the transaction with Shaw, its biggest deal ever, by the first half of next year pending regulatory approval. Loretta, Martha, and Melinda hinted in their own statement that they worry the court outcome could imperil the deal. “The company now faces a very real prospect of management upheaval and a prolonged period of uncertainty, at perhaps the worst possible time,” they said.

Under any circumstances, a deal of this size would require a steady CEO to navigate the heightened scrutiny from regulators and politicians over antitrust concerns. Canadian industry is dominated by family dynasties and state-protected behemoths that enjoy extraordinary concentration and pricing power. Five banks are a near-oligopoly. The dominant Big Three telecoms—Rogers Communications, Telus, and BCE—charge among the world’s highest mobile rates. That group would lose its next-biggest competitor if the Shaw deal goes through.

The turmoil further raises those risks by lending credence to rival telecom companies’ arguments to regulators that Rogers Communications isn’t fit to govern such a large enterprise, says Richard Leblanc, a professor of governance, law, and ethics at York University. “It’s a poor day for corporate governance when one person has this much authority leading a major public company,” he says of the ruling. “I have never seen a concentration of power like that.”

Despite the ruling, the real-life boardroom drama befitting television might not end easily, if ever. For shareholders, who’ve provided about 70 per cent of Rogers Communications’ equity but carry almost no votes, a thorny problem looms: a company at the mercy, potentially in perpetuity, of a squabbling family and, for now, one extraordinarily powerful man.

THE BEGINNING OF AN EMPIRE

Ted Rogers was 5 years old when he went to bed to the sound of his parents hosting a dinner party at their Toronto home in 1939. It was the last time he would see his father, Edward Samuel Rogers, an inventor and pioneer in the radio industry, who died of a ruptured aneurysm at age 38. Within two years, his mother gave up control of the family business amid a feud with her late husband’s brother. The young Ted watched his father’s companies get sold and shuttered and his mother driven to alcoholism, but not before she hammered into him a zeal to one day reclaim the family’s communication business, according to his authorized biography, Relentless, written with Robert Brehl.

Ted Rogers won it back—and then some. Starting in 1960 with a fledgling FM radio station, bought with a $85,000 loan, he became one of the greatest entrepreneurs and dealmakers Canada has ever seen. With a voracious appetite for risk and a knack for spotting emerging technologies years ahead of rivals, he placed huge bets on cable TV, broadband internet, and wireless telecommunications with the fearlessness of a man running out of time.

Eventually, Ted expanded his company into a communications and media empire that included dozens of TV and radio stations; Maclean’s, Canada’s most influential current affairs magazine; and the country’s only Major League Baseball team, the Toronto Blue Jays. “ROGERS”—all caps, in bull’s-eye red—became a nationwide icon, emblazoned across stadiums and storefronts. As a 2014 family profile in Toronto Life put it: “You can’t swing an old corded telephone in this town without hitting something owned by the Rogers family.”

It was an empire built on an unflinching tolerance for debt. There were times Ted would toss all the unpaid bills in a hat at the end of the week and draw the ones he’d pay until the money ran out. For his 50th birthday, his bankers gifted him a fake certificate as a joke—a $50 billion line of credit. He skirted financial ruin several times. For much of his life, he battled health problems and remained haunted by his father’s early death.

At age 35, soon after adopting his first child, Lisa, Ted began succession planning to ensure the family would retain control of what he’d built. Loretta subsequently gave birth to Edward, Melinda, and Martha. Melinda was known to be the one most like him and was considered a star. Tall, striking, with a razor-sharp intellect and an MBA from Canada’s top business school, she acquired the nickname “Ted in a skirt.” Melinda became highly involved in the company, holding roles in strategy including starting a venture capital arm in Silicon Valley, while Lisa and Martha pursued careers outside the family business.

After Edward graduated college (where he appeared to have excelled at frat-house pranks more than his studies), he was sent to Towson, Maryland, for some outside work experience. Calling up the controlling family of Comcast Corp., Ted asked them to give Edward “every lousy job they could,” the patriarch recounted in his biography.

Two years later, Edward returned to Canada and began rising through the ranks. By his 30s he was named president of the cable unit. Conservative, careful with finances, and awkward, Edward was his father’s opposite. A couple of years before his death, Ted said his son was “like a fine wine, he needs some time to mature,” according to former journalist Caroline Van Hasselt’s 2007 book, High Wire Act. Edward’s public image was spiced up by his fashionable wife, Suzanne, who hobnobbed with Oscar de la Renta and Victoria Beckham. Earlier this year, Suzanne posted (and then deleted) a photo on Instagram of her and Edward posing with Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago Club.

It was no secret Edward and Melinda didn’t get along, and the question of succession festered for years. Still, Ted was clear that the company’s board would determine who followed him as CEO. What he spent four decades planning, however, was an elaborate dual-class share structure that gave the Rogers family members outsize voting rights and ensured the family would retain its hold over generations.

Under Ted’s setup, the control of Rogers Communications remained firmly in the hands of his descendants, with ownership of more than 90 per cent of the voting shares. Instead of dividing the spoils among his children and his wife, he forced them to work together by putting shares in a trust governed by a 10-member council comprising Loretta, the children, relatives, and Ted’s most trusted advisers. The aim was to keep the family united and voting as a block. But Ted also believed someone ultimately had to be in charge: the trust chair.

When he died in 2008, that someone became Edward, in a move that Ted told his biographer Brehl was designed “so they don’t all have a meeting over my grave and scream and yell at each other.” How wrong he was.

THE SHOWDOWN

The first sign to the public that something was amiss came in an evening press release on Sept. 29, abruptly announcing the departure of Staffieri, who’d served as Rogers’s chief financial officer for almost a decade. Turnover at the highest ranks of Rogers hadn’t been all that unusual since Ted’s passing. The company has had three CEOs since (and one interim). Nadir Mohamed, who’d been Ted’s second-in-command and his top pick as successor, ably steered the company for nearly four years but left after reportedly asking that Edward and Melinda be stripped of their executive roles. Guy Laurence was hired next, to great fanfare (he’d led a turnaround at Vodafone UK Ltd.), but within three years he’d stepped down. And then Natale, who previously held the top job at rival Telus Corp.

Analysts chalked up Staffieri’s departure to a personnel realignment ahead of the Shaw integration. What the public didn’t know at the time was that Staffieri was a casualty of a boardroom coup heating up behind closed doors. Twelve days earlier, Natale had dialed Staffieri, who accidentally accepted the call; for the next 21 minutes, Natale listened undetected as Staffieri spoke with a former colleague and, according to court affidavits, unwittingly laid bare a plot to reshuffle the company’s entire top management. Edward planned to fire Natale, install Staffieri as CEO, and oust most of the executive leadership team, all in one fell swoop. Edward banked on the board rubber-stamping it all, an expectation that showed a lack in corporate governance norms but a practice that had nonetheless been customary at Rogers since the days of Ted, who favored loyalty over independence on his board.

Instead, Edward touched off a dizzying sequence of events. On Sept. 19 he followed through with his plan, firing Natale. Five days later he presented the CEO’s departure to the board as a fait accompli, asking the directors to sign off on the exit package, according to an affidavit by John MacDonald, lead director at the time (later to replace Edward as chairman as the dispute escalated).

The move backfired spectacularly. Longtime independent director David Peterson, enraged by Edward’s usurping of the board’s authority, spent the weekend rallying Natale and other directors to fight back, assuring the CEO he had the necessary support to save his position at the company. On Sept. 29, Edward’s mother, Loretta, and his sisters Melinda and Martha, joined with five independent directors in voting to keep Natale, enhance his pay package, and fire Staffieri. They also established a new executive oversight committee to restrict Edward’s interactions with management.

Edward had no intention of rolling over. Instead he doubled down, thrusting the Rogers family into deeper acrimony. With the support of Alan Horn, one of Ted’s most loyal executives, and other long-standing allies, Edward prepared to unseat the five directors who’d obstructed him. But to do so he needed a complete list of the company’s Class A voting shareholders to inform them, per disclosure rules, of his proposed resolution to reconstitute the board.

Weeks passed as Edward tried to get his hands on the list, while the board stalled. Finally, on Oct. 20 the company handed it over to him. The next day, at a meeting of the family trust, Loretta urged the group to avoid a “needless public spectacle,” and Melinda proffered a cease-fire: Edward would remain chairman of Rogers in exchange for him dropping his demand for new directors, which he rebuffed. Loretta, Melinda, Martha, and a longtime family adviser voted to constrain Edward’s power but were defeated. Immediately after, the company’s board voted on a motion proposed by Loretta to remove Edward as chairman.

That night, the letter to Class A voting shareholders went out. In it, Edward informed shareholders that as controlling chair of the family trust, he intended to pass and execute the resolution himself. “You are not required to sign the Resolution or take any other action,” the letter said to the remaining 2.5 per cent of voting shareholders.

On Oct. 22, Edward signed the resolution. And, according to a letter his lawyers sent to the company, “it took immediate effect as it was executed by holders of over 97 per cent of the Class A shares.”

That day, Martha took her grievances against her brother public on Twitter. Over the next week, dozens of her cutting tweets provided a rare glimpse into the pain and dysfunction consuming the Rogers empire. “We’ll spend every penny defending the company, employees & Ted’s wishes,” she wrote on Oct. 23. “Bring. It. On.” The following day she posted, “Enjoy your pretend ‘board meeting’, Ed. Here’s your problem: it’s not legal.”

Edward didn’t flinch. On Oct. 24 he called a meeting with the “new board,” as he’s called it, where the directors appointed him as chairman. In return, the company declared the meeting and the appointment invalid.

On Oct. 26, Edward initiated proceedings before the Supreme Court of British Columbia seeking an order to legitimize his board. Things only got messier from there, as a flurry of sworn affidavits filed in court appeared to reveal a potentially duplicitous side to Edward. In one such sworn affidavit, MacDonald, the lead director-turned-chairman, said Edward misled him about a key management decision and also about having his family’s backing. Another contained the text of a board speech that Loretta delivered initially in support of Edward’s new management structure, which Edward stated she’d prepared with his and Martha’s help. At the time, the 82-year-old matriarch had been led to believe by Edward that Natale wasn’t meeting performance metrics. In hindsight, she says her son misled her. “I did not draft the statement,” she swore in the affidavit. Edward and his allies wrote it, she said.

On Friday, Justice Shelley Fitzpatrick ruled in favor of Edward. “These family squabbles are an interesting backdrop to this dispute that would be more in keeping with a Shakespearean drama,” she noted, but “at best, they are a distraction.” The legal issue was narrow: Edward had complied with both the law and the company’s articles to reconstitute the board, she said. “I am granting the order sought by Edward.”

THE AFTERMATH

Edward may have prevailed in the legal fight for now, but the court decision does nothing to heal the rift cleaving one of the nation’s wealthiest families. Loretta had argued in her affidavit that Edward’s campaign was “unconscionable,” going against the expressed wishes of his late father, who’d also intended for control of the family trust to rotate.

“Our control over the company was never intended to be absolute,” Loretta said. “The independent directors that Edward tried to remove had done exactly what shareholders expect of them—they spoke truth to Edward’s power.”

Edward may have stirred up more trouble than he bargained for. Under his original plan, as many as nine of 11 senior executives on Natale’s team were to depart. But he’d planned to elevate Dave Fuller, who runs the company’s wireless division, the most important business, accounting for 59 per cent of its revenue. Now, Fuller has said that if Natale goes, he goes. “I do not wish to work for any other CEO,” he said in an affidavit.

Just a couple of hours after the court ruling, Martha took to Twitter again. She posted her family’s statement, in which they expressed disappointment in the decision and called it “a black eye for good governance and shareholder rights.” She also wrote, #EdRogersSaga #OldGuardDown.