May 26, 2021

Investors Bet Billions That Health Care's Long Overdue Digital Shift Is Finally Here

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Investors are pouring a record amount of money into young companies trying to transform U.S. health care at an accelerating pace.

Spurred by the pandemic, private funding for health-care companies has reached new highs every quarter since Covid-19 emerged. Investors steered a record $6.7 billion to U.S. digital health startups in the first three months of 2021, according to venture firm and researcher Rock Health. In 2011, Rock Health tracked $1.1 billion invested in digital health for the entire year.

The flood of money is getting attention from new corners. JPMorgan Chase & Co. last week announced a new business with a $250 million investment arm to transform employer health coverage. Young startups have closed giant deals like the $500 million that online pharmacy Ro, founded in 2017, raised in March. And venture-backed health companies are reaching the public markets: Upstart insurer Bright Health Group, founded in 2015, filed for an initial public offering last week.

Sustained low interest rates have investors searching for returns in new arenas, pushing money into assets from junk bonds to Dogecoin. Venture capital is no exception -- with funds raising $32.7 billion in the first quarter, on pace to exceed last year’s record, according to data from the PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor.

All that money has to go somewhere. As the pandemic eases in the U.S., a growing chunk of venture capital has decided that the upheaval spurred by Covid-19 is accelerating shifts already underway in the notoriously inefficient $4 trillion U.S. health-care sector.

Big ambitions have fizzled before: Before JPMorgan’s latest health venture, the bank abandoned its joint effort with Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway. Yet investors believe the pandemic catalyzed lasting changes in how Americans get health care that have been predicted for years.

“The health-care industry is kind of 10 to 20 years behind all other modern industries in terms of adopting innovation,” said Steve Kraus, a partner at venture firm Bessemer Venture Partners and a board member at Bright Health.

Kraus started investing in health care a decade ago, when many U.S. medical providers still relied on paper records. Now he says the industry is catching up. “It happened so quickly, and it happened so quickly because of Covid,” Kraus said.

Moving Fast

One sign of how quickly money is moving: Health-care startups are raising fresh rounds of funding just as the ink barely dries on their term sheets. Dozens of digital health companies raised more than one funding round during 2020, according to data compiled for Bloomberg by Rock Health, a pace that was almost unheard of a few years ago.

The surge of cash into such firms is a multi-billion dollar bet that health care is finally ready for the kind of technological change that long ago recast retail, software and media. Such shifts mint new fortunes and threaten old business models. Investors are racing to back the companies they hope will become the Amazon, Salesforce or Facebook of health care.

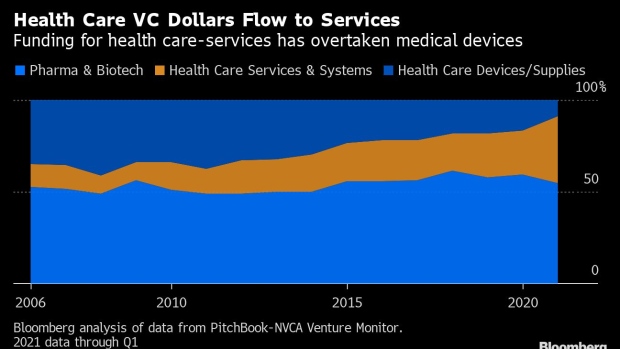

Venture capital in health care has long been focused on developing new drugs and medical devices. The risky, costly business of new drug development still gets the lion’s share of health-care venture investment.

But money is increasingly moving into health services and software. In the past few years, funding in those areas exceeded the amount going toward medical devices, according to data from the PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor. As the total amount of venture investment rose in that period, digital health and other services businesses make up a growing slice of a growing pie.

What accounts for the shift? Many health-care organizations until recently relied on paper records. Ten years ago, just more than a quarter of U.S. hospitals had adopted basic electronic health records that could hold clinicians’ notes, according to federal data. The U.S. government invested more than $35 billion to prod health-care providers into electronic record-keeping, and the industry is moving toward more fluid data exchange among different entities -- albeit haltingly.

“There’s just more infrastructure to build on top of for digital health companies,” said Megan Zweig, chief operating officer of Rock Health. “It is easier now to build a company than it was five or 10 years ago.”

There are other factors at play. The Affordable Care Act encouraged payment arrangements meant to tie reimbursements to patients’ health outcomes, not simply the volume of care delivered. High rates of chronic conditions and a rapidly aging population drive demand for tools that help people manage their health and live independently for longer. And people of all ages increasingly expect to get health care the way they now get so much else: Through screens on computers and phones.

Pandemic Acceleration

These trends were in motion before the pandemic, but Covid-19 broke down an important barrier that deterred some investors from the health care segment: Inertia. Potential customers like insurers, employers and hospitals tend to be risk-averse and sluggish adopters. Startups building products for those markets could burn through cash quickly waiting for organizations to take a risk on trying something new.

“You had this problem of growth being slow, and very expensive,” said Bob Kocher, a partner at Venrock and longtime digital-health investor. “That kept valuations low-ish and scared away a lot of tech investors.”

Covid changed that almost overnight, as physical distancing forced doctors and hospital systems to switch to remote visits. The pandemic “compressed into six months like 10 years of adoption of things like virtual care and telemedicine,” Kocher said.

Fundraising is accelerating in turn. Digital health companies are raising bigger amounts of money sooner than they used to. In the first quarter, 17 companies raised rounds of at least $100 million, according to Rock Health’s data. That’s almost as many as in 2018 and 2019 combined. And companies are reaching those big “megadeal” moments earlier, on average just five years years after they were founded.

Some of that capital may fuel consolidation in the months and years ahead. Rock Health’s Zweig said companies marketing to employers and health plans are hearing that their potential customers are overwhelmed by the proliferation of “point solutions” — narrowly targeted products for particular medical conditions or types of care, like diabetes or musculoskeletal disorders.

The market is seeking broader offerings, she said, and some of the cash landing in startup’s treasuries will likely go toward acquiring other startups and assembling more sweeping offerings.

A growing number of digital health companies have gone public or been acquired at attractive premiums, “exit” events that give venture investors payouts and have bolstered VCs’ confidence in the industry. “For a while there were not a lot of exits in digital health and now there are, and investors like exits,” Zweig said.

High-profile IPOs and acquisitions in recent years caught investors’ attention by proving how quickly digital health startups can multiply their money. Over a decade, a digital health startup trying to improve diabetes care quietly raised about $240 million in venture capital. The company, Livongo Health, debuted in 2019 in an IPO valuing it at $2.6 billion. The next year, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was acquired by Teledoc Health Inc. for almost $13 billion, five times its value when it went public.

“All of a sudden investors said, ‘Wow, you can make a lot of money in this,’” said former Livongo CEO Glen Tullman, who is now leading a fresh venture called Transcarent. “These companies are real.”

Frenzied Financing

Kraus, who is on the investment committee at Rock Health, acknowledges that dealmaking is at frenzied pace. “Are valuations high? For sure. Is deal velocity too quick in my mind? For sure,” he said. “There’s a lot of capital chasing companies.”

But he said he doesn’t see a bubble in the sense of irrational funding of companies with few prospects for sustainable business. Instead, he sees companies with solid ideas going after real market opportunities in an industry long overdue for change.

Large incumbent companies are increasingly promoting visions of a high-tech health-care future. Anthem Inc., the nation’s second-largest health insurer, told investors in March not think of it as a health insurer, but as “a digitally enabled platform for health,” in the words of Chief Executive Officer Gail Boudreaux. Cigna Corp. purchased telehealth provider MDLive in February, and Walmart Inc. is buying a telehealth company called MeMD. CVS Health Corp. has announced a new $100 million corporate venture fund focused on digital health.

Yet to be seen is whether the flood of innovation will dent the fundamental problem of U.S. health-care: The price tag. Employers, taxpayers and households collectively devote $4 trillion a year, or about 18% of the gross domestic product, a far higher share than most wealthy countries. That outsize spending doesn’t lead to longer lives or better health compared to countries that spend far less.

Investors and entrepreneurs looking to transform health care shouldn’t underestimate how hard it is. “The tech people who haven’t really spent enough time in the health policy world say, ‘Oh, we’ll just show up and figure it out,’” said Paul Hughes-Cromwick, a health-policy consultant in Ann Arbor, Mich.

Almost every startup raising money promises to improve care, lower costs, or both. For new companies to both make money and lower overall costs, a reduction in health expenditures has to come from somewhere else — that is, out of someone else’s revenue stream. Otherwise, innovations may just add costs to the system.

Some essential parts of medicine like surgeries or physical exams won’t be replaced. “That human interaction won’t go away,” Hughes-Cromwick said. “There’s kind of a limiting factor for what technology could do. But I’d be a fool to say it’s not going to do those things.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.