Nov 8, 2021

Investors Pushed Mining Giants to Quit Coal. Now It’s Backfiring

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- It was supposed to be a big win for climate activists: another of the world’s most powerful mining companies had caved to investor demands that it stop digging up coal.

Instead, Anglo American Plc’s strategy reversal has become a case study for unintended consequences. Its exit has transformed mines that were scheduled for eventual closure into the engine room for a growth-hungry coal business.

And while it’s a particularly stark example, it’s not the only one. When rival BHP Group was struggling to sell an Australian colliery this year, the company surprised investors by applying to extend mining at the site by another two decades — an apparent attempt to sweeten its appeal to potential buyers.

Now, after years of lobbying blue-chip companies to stop mining the most-polluting fuel, there’s a growing unease among climate activists and some investors that the policy many of them championed could lead to more coal being produced for longer. Senior mining executives say the message from their shareholders is evolving to acknowledge that risk, and they’re no longer pushing as hard for blanket withdrawals.

BHP may end up holding on to the Australian mine it was battling to sell, Bloomberg reported last week. Earlier this year, Glencore Plc sounded out a major climate investor group before announcing it would increase its ownership of a big Colombian coal mine, according to people familiar with the matter.

“Everyone in the industry is starting to be more sophisticated, more nuanced and more careful on the way they think these issues through,” said Nick Stansbury, head of climate solutions at Legal & General Group Plc.

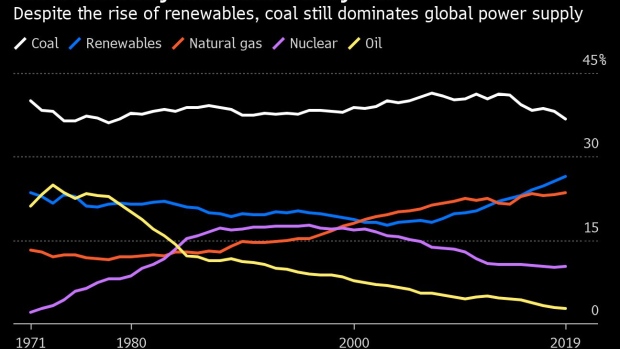

Who should own the world’s coal mines is a question that resources giants and their investors may be grappling with for years to come. At the global climate talks in Glasgow, world leaders have fallen short on the U.K. host’s ambition to “consign coal to history.” It continues to dominate the world’s electricity mix and energy shortages in Europe and China this year have only reinforced the message that the world remains deeply dependent on coal.

The campaign to force coal out of the hands of the biggest diversified miners kicked off about a decade ago, with limited success. That changed after some of the world’s most powerful investors, including Norway’s $1 trillion wealth fund and BlackRock Inc., began introducing policies to limit their exposure to coal.

Read more: COP Aims to End Coal, But the World Is Still Addicted

By early 2020, pressure was mounting on Anglo American boss Mark Cutifani. He’d already watched rival Rio Tinto Group sell its last coal mines. BHP was looking at options to get out and even Glencore, coal’s biggest champion, had agreed to cap its production.

Cutifani’s original plan had been simple: it was increasingly unlikely that Anglo would invest more in its seven South African mines — which accounted for a fraction of its overall profits — and the company would ultimately close them when they ran out of coal over the next decade or so.

But for some investors that wasn’t soon enough.

The solution Anglo came up with was a spinoff company — Thungela Resources Ltd. — to be run by a senior Anglo executive, and handed over to its own shareholders.

The plan meant Anglo could get out of coal without having to cut any jobs in a country facing massive unemployment, and leave the mines in trusted hands until they were depleted. Anglo investors could decide for themselves whether to hold or sell the shares they received.

Yet within days, Chief Executive Officer July Ndlovu was laying out big ambitions for the company and its mines. Thungela was looking to grow, not shrink coal production, he said.

“I didn’t take up this role to close these mines, to close this business,” Ndlovu told Bloomberg at the time.

The company’s Zibulo, Mafube and Khwezela mines have the potential for extension to add at least another decade of mining and perhaps much longer, producing more than 10 million tons of coal a year.

Thungela’s creation has come at a time of great flux for the industry. As the global economy recovers from the pandemic, demand for electricity and the fuels used to produce it surged around the world, sending thermal coal prices to the highest on record.

That’s meant windfall profits for producers and their investors, making it more lucrative to keep digging as much as possible. Thungela’s shares have soared since its June initial public offering, although they’ve pulled back recently as coal prices eased.

With billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of jobs at stake, the question has always been who — f not the publicly traded mining companies — should be running their collieries?

Companies like Anglo and BHP have long argued they are the most responsible operators, with deep pockets and sophisticated approaches to climate, the environmental impact of their operations and worker welfare. There is no guarantee new owners will act in the same way, or have the financial muscle to ride our volatile swings in commodity prices.

“Selling the problem to a third party has unintended consequences,” said Ashley Hamilton Claxton, the head of responsible investment at Royal London Asset Management, who argues that mining companies should hold onto fossil fuel assets and manage their decline. “We need to shift the debate in the investment industry about being more sophisticated around these things.”

It’s a theme that has played out elsewhere. Some observers of the oil industry say campaigns by activists to have oil majors divest from fossil fuels could end up accelerating a shift to government owners who operate with less transparency and, occasionally, worse environmental records.

In an attempt to fill the gap, other ventures have sprung up. Citigroup Inc. and Trafigura Group were one, pitching a coal-focused company to investors early this year, with the idea that it could snap up cheap mines and run them for cash — not growth — before eventually closing them.

But there’s also growing evidence that investors are changing their approach.

When BHP and Anglo wanted to sell their stakes in a big Colombian coal mine earlier this year, the third partner, Glencore, was the obvious buyer. In the past, a move to increase its exposure to coal might have drawn criticism from climate-focused investors. The company already agreed in 2019 to cap its coal production, under pressure from Climate Action 100+, an investor group with 545 members managing a combined $52 trillion of assets.

As Anglo and BHP pushed to sell the mine, Climate Action became a surprising behind-the-scenes sounding board for Glencore, according to people familiar with the matter. The group saw the transaction as a way of preventing any mine extensions or the asset being passed to a less responsible owner. Glencore agreed to further tighten its emissions-reduction goals as part of the deal.

While Climate Action has not spoken out publicly, the Colombian purchase was seen by many in the industry as further proof that investors’ positions have fundamentally changed.

Meanwhile, BHP, which has been planning an exit from thermal coal since at least mid-2019, has rejected multiple approaches for its Mt Arthur mine in Australia. The sale has dragged on as the pool of potential buyers dwindled and the offers it got were either too low or rejected because the company didn’t consider them responsible new owners.

Earlier this year, it emerged that BHP had applied to extend the mine’s life by almost 20 years. It didn’t take long for concerned investors to start asking why the company was preparing the mine to keep digging coal for longer.

Since then, pressure has mounted on BHP to u-turn on its exit strategy. Market Forces, which coordinates groups of shareholders on climate issues, has called on the company to abandon plans to sell out of fossil fuels, and instead responsibly close down the operations.

“The big push from investors is around ensuring that any divestment that occurs is to parties that are responsible,” BHP CEO Mike Henry said at the company’s shareholder meeting in October.

Now, the sale process appears to have stalled and the company could end up keeping Mr Arthur, after coal’s rally made the asset more valuable, and it’s no longer under as much pressure from some investors to sell, people familiar with the matter said.

Glencore, meanwhile, has promised to run its coal business to closure by 2050, which received overwhelming support from its shareholders, but it’s also prepared contingency plans to exit should investors force it. The developments of the past six months suggest that’s looking less likely.

“Divestment is convenient and easy to communicate,” said Hamilton Claxton. “Helping companies manage decline is difficult to do from an investment perspective and showing our customers that we’ve been effective is difficult to do.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.