Oct 12, 2020

Investors Should Be Wary of SPACs. Also Red Sox Fans.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Every few years, investors seem to become enamored with one investment or another. In my adult lifetime, it started with internet companies in the late 1990s, then residential real estate in the mid-2000s, and more recently cryptocurrencies and pot stocks. It always ends the same way, with investors rushing in to get rich only to stumble out disappointed or worse.

Enter the latest obsession: so-called blank check companies, formally known as special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs. In a sure sign that investors are on the chase, a new exchange-traded fund, the Defiance NextGen SPAC Derived ETF, now offers one-trade access to would-be SPAC investors. It follows a gaggle of big-name figures who are launching SPACs to cash in on the craze, among them hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman, former U.S. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Oakland A’s executive Billy Beane, whose SPAC is reportedly in talks on a deal with the owner of the Boston Red Sox.

So what’s a SPAC? In essence, it’s a shell company that attempts to acquire a private business and take it public. Here’s how it works: The SPAC raises money from investors in a public offering. It then goes shopping for a business. If a deal is struck, the two merge and the SPAC takes the name of the business, leaving a single public company. Alternatively, if the SPAC fails to acquire a business, generally within two years, investors get their money back.

The best-known example so far this year is probably the deal involving DraftKings Inc., an online sports betting company. Diamond Eagle Acquisition Corp., a SPAC, bought DraftKings for $3.3 billion in April and took its name after the two merged. And just like that, DraftKings is publicly traded. It’s also the biggest holding in the Defiance ETF, with a whopping 16% allocation.

The appeal to private businesses looking to go public is plain. Merging with a SPAC allows them to sidestep much of the uncertainty, effort, expense and public and regulatory scrutiny that comes with a traditional IPO. The appeal to SPAC sponsors — the organizers who run it and hunt for businesses — is even clearer. If they strike a deal, they’re able to purchase 20% of the business for next to nothing — a gold mine if the share price takes off after the merger, as DraftKings’ stock has done since it combined with Diamond Eagle. That’s on top of the money promoters make just for showing up.

What’s in it for investors is less obvious. For one, SPACs don’t have a great track record of delivering deals. Of the 313 SPAC offerings since 2015, only 93 have taken a company public, according to IPO research firm Renaissance Capital. And most of those deals have been a bust. “The common shares have delivered an average loss of -9.6% and a median return of -29.1%, compared to the average aftermarket return of 47.1% for traditional IPOs since 2015,” Renaissance found. Only 29 of those SPACs produced positive returns through September.

Despite those sobering results, investors may be lured by the exits SPACs offer. In addition to getting their money back if the SPAC fails to find a business to buy, investors can redeem their shares if they don’t like the proposed deal. But that doesn’t mean rolling the dice on a SPAC is free or without risk. SPACs aren’t cheap to operate, and those expenses fall on investors whether they get a deal or not. And if investors want out, there’s no guarantee their shares will be worth what they paid for them.

That is, assuming investors can get out. Remember that promoters must find a company to take public if they want a shot at the big payday, so they have every incentive to deliver a deal — any deal. And once promoters have a company in their sights, they’re likely to tickle investors’ greed with promises of fat profits. It’s easy to get carried away in that moment and to waive away the fact that promoters are taking a big chunk of any upside, a load that would make high-priced mutual funds blush.

So far, the money poured into SPACs has mostly come from hedge funds and other institutional investors, but that’s beginning to change. Big banks are showing up among the holders, which is often a sign that they’re stuffing the investment into portfolios they manage for clients. Ordinary investors are next, if the flood of recent articles about how to invest in SPACs is any indication.

Indeed, SPACs may be most tempting to ordinary investors. Companies are staying private longer than they used to because private capital is abundant and allows them to dodge the scrutiny of public markets. At the same time, securities laws deny ordinary investors access to private markets, forcing them to watch from the sidelines as countless businesses they patronize and admire, such as Airbnb, Instacart, Robinhood and DoorDash, grow from seedlings into multibillion-dollar companies. SPACs offer ordinary investors a backdoor — albeit a very expensive and speculative one — for investing in private businesses before they go public.

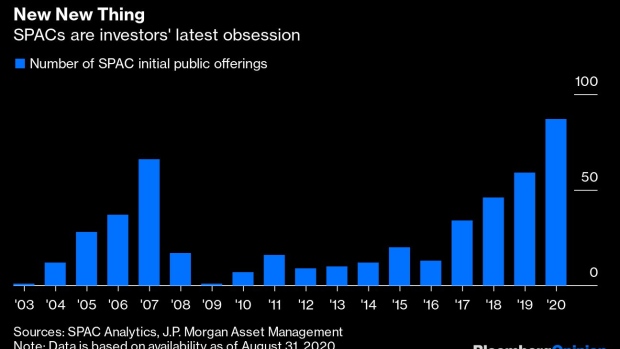

So the SPAC boom may just be getting started, and it’s already the biggest on record. Unlike internet stocks in their 1990s heyday, and cryptocurrencies and pot stocks more recently, SPACs have been around for decades. And this isn’t their first taste of success. In 2007, the number of SPAC offerings swelled to 66 from just one in 2003, according to J.P. Morgan Asset Management, until the 2008 financial crisis crushed demand. So far this year, nearly 90 SPACs have already gone public through August, and more are expected. Thanks to the abundance of big private companies, there’s plenty of potential supply to feed the surge in demand for SPACs.

That’s not the only difference between SPACs and earlier fads. SPACs have the curious distinction of asking investors to hand over their money without knowing where it will go. With dot-coms, homes, cryptocurrencies and pot stocks, investors knew what they were buying, or at least had the opportunity to find out. That’s not even possible with SPACs. Everyone with a bank account has been warned about signing a blank check. The same caution applies to SPACs.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.