Sep 17, 2021

Iron ore’s brutal collapse under US$100 flags more trouble ahead

, Bloomberg News

Iron ore fell below US$100 a metric ton for the first time in 14 months as China’s moves to clean up its heavy-polluting industrial sector drive down demand for the steel.

Futures prices sank to as low as US$99.50 on the Singapore Exchange and wavered around US$100 through the overnight trading session, which is daytime trading hours in the U.S. Iron ore has plunged more than 55 per cent since peaking in May as the world’s biggest steelmaker intensifies production curbs to meet a target for lower volumes this year, and a sharp downturn in China’s property sector hurts demand.

The slump in the steelmaking ingredient shows how top consumer China could sway the market at a time when there’s booming demand in the broader commodities market as economies reopen from the worst of the pandemic.

“Dramatic declines in iron ore prices” are mainly built on the view that “this year’s effort will likely be strictly enforced,” said Ed Meir, an analyst at ED&F Man Capital Markets.

Iron ore futures plunged more than 20 per cent this week and traded at US$99.60 at 11:53 a.m. New York time.

Past efforts by Beijing to rein in steel production due to environmental concerns had largely failed as local governments weighed regional economic growth against clean skies.

Iron ore’s slump makes it one of the worst-performing major commodities and a notable outlier in a broader boom that has seen aluminum soar to a 13-year high, gas prices jump and coal futures surge to unprecedented levels.

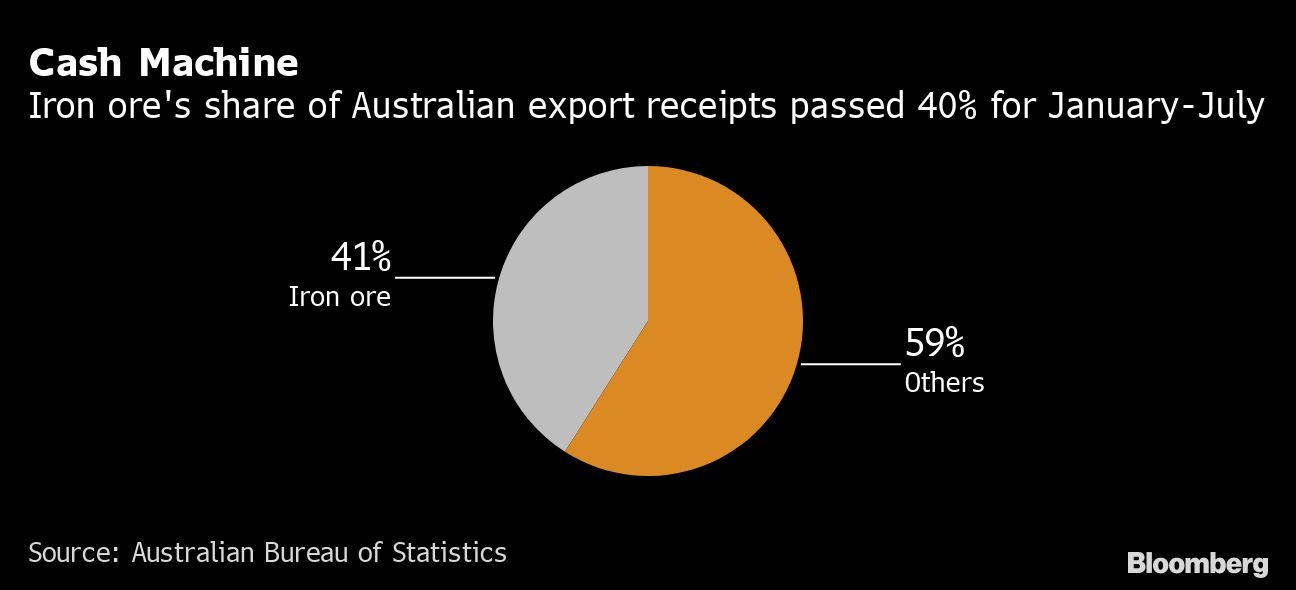

A drop back to double-digits for the first time since July 2020 would be a relief for steel producers, but a blow to the world’s top miners that have enjoyed bumper profits during the first-half rally. It’s bad news too for top iron ore producer Australia, where the key steelmaking ingredient generates about 40 per cent of goods exports.

Here’s more on iron ore’s collapse and how it may ripple through markets:

LOSING A DIGIT

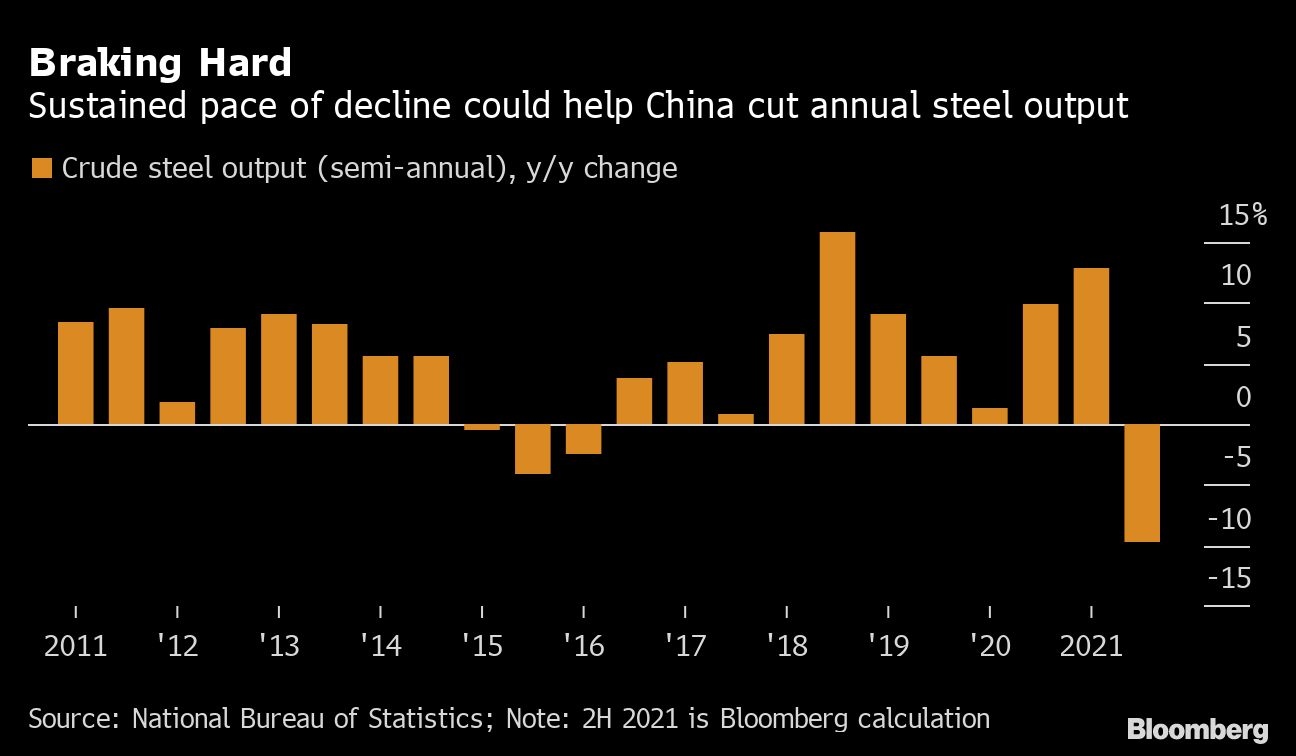

It has been a stark turnaround from the first half, when steelmakers ramped up output and economic optimism and stimulus aided consumption. The rally then faltered after China began cracking down on surging commodity prices, and the decline gathered pace as authorities rolled out more measures to reduce steel production and end-user sectors like property weakened.

Iron ore’s deepening selloff has seen volatility jump to the highest in five years, with UBS Group AG saying the decline “has played out faster than expected.” Inventories at ports are 10 per cent higher than a year earlier and expectations for Chinese demand to soften further coincide with forecasts for global supplies to rise. UBS predicts prices will average US$89 next year, a 12 per cent cut to its previous forecast.

STEEL SURGE

It’s a different story for steel, where prices have stayed elevated. The market remains tight of supplies as China’s production cuts significantly outpace declining demand, according to Citigroup Inc. Spot rebar is near the highest since May, albeit 12 per cent below that month’s high, and nationwide inventories have shrunk for eight weeks.

China has repeatedly urged steel mills to reduce output this year to curb carbon emissions. Now, winter curbs are looming to ensure blue skies for the Winter Olympics.

Measures are starting to take effect, with production dropping to the lowest in 17 months in August and declining in early September. Volumes need to fall 8.7 per cent year-on-year in the final four months to achieve flat annual output, according to China International Capital Corp.

MAJOR MINERS

Iron ore producers Rio Tinto Group, BHP Group, Vale SA and Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. have seen their shares tumble. The drop in prices is likely to weigh on profit that had surged alongside the earlier jump.

The biggest producers are able to weather lower prices as their production costs can be less than US$20 a ton, but smaller miners will be hit harder. Those operators tend to restart or ramp up production when the market rallies strongly, and processes such as having to truck ore from mines to ports make them more sensitive to price changes.

ECONOMIC HIT

Australia’s economy had been supported through the pandemic by surging iron ore export revenue. But the country’s growth is under increasing pressure from lockdowns in its two biggest cities and every US$10 decline in the price of iron ore has a A$3 billion (US$2.2 billion) to A$3.5 billion fiscal impact, according to Bloomberg Economics.

For China, iron ore’s slump has come as authorities grapple with stemming a surge raw material costs that had stoked concerns that rising inflation would curtail growth.