Jun 9, 2022

It's Getting More Expensive to Have Your Period, Thanks to Inflation

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Inflation has come for period products, making it harder for US consumers with already stretched wallets to afford basic hygiene supplies they can’t skip.

Average prices rose 8.3% for a package of menstrual pads and 9.8% for tampons in the year through May 28, according to NielsenIQ. Personal-care goods, a broad category that includes period products and items such as shampoo and shaving equipment, saw their biggest annual price jump since August 2012, April figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics also show.

The increases are squeezing shoppers, especially low-income consumers already struggling with the highest inflation in four decades. Unlike with shampoo or razors, though, people with monthly periods can’t easily cut back on consumption or wait for prices to decline. The cost of period goods aren’t covered by federal assistance programs, nor are they exempt from most states taxes.

Manufacturers of period goods are passing on higher costs for logistics and key components. Prices for plastic resins and materials climbed 9.5% in April from a year ago, according to the US government’s latest producer price index. Cotton futures surged 40% in the past year, and fluff pulp, an absorbent fiber derived from trees, jumped 25% in the 12 months through June 1, according to data provider Fastmarkets RISI.

“In terms of the speed of the increase, it’s the sharpest I’ve ever seen,” said Pricie Hanna, a consultant with almost four decades of experience in the industry. “At this point, people are scratching their heads and saying, ‘This is something new.’”

The price leaps put particular pressure on low-income women, many of whom already struggle to buy period products. Procter & Gamble Co., which makes brands such as Tampax and Always and has a near-50% market share in menstrual-care supplies, recently announced a fresh round of price hikes on top of increases from about a year ago.

The top layer of most pads is made from plastic fibers bonded into sheets. Under that outer surface, the material that soaks up liquids consists of fluff pulp and super-absorbent polymers with a chain-link-fence molecular structure that forms a gel that can hold multiple times its weight in fluids. Tampons use cotton or rayon for absorbency.

Supply Chain Stress

The supply chains for each of these components are under stress. Plastics and super-absorbents come from oil, which is priced about 70% higher from a year ago, due in part to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Demand for the polymers is also rising as companies seek to make diapers, period products and incontinence goods thinner and more comfortable, Hanna said.

It doesn’t help that some US plastics makers have shut down for maintenance after months of operating at full throttle to fulfill a deluge of orders for everything from masks to e-commerce packaging to takeout containers, said Howard Rappaport, a senior adviser at StoneX Group Inc., a New York-based trading and research firm.

Meanwhile, prices for fluff pulp have increased due to a demand and supply imbalance made worse by high costs for transportation, labor and the natural gas that powers many mills, said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Ryan Fox. Cotton availability has also been under threat due to extreme drought, including in Texas, the top producing American state. This is fueling expectations that overall cotton production could decline in the US, the world’s biggest exporter.

Transporting goods has also become more expensive. Record-high US diesel prices have cut into drivers’ profitability to the point that some are declining to carry loads, said Dave Rousse, president emeritus of INDA, an industry association whose members include P&G and Kimberly-Clark Corp.

Some economists have argued that, in addition to rising input costs, higher prices for consumer goods are a result of corporate power, which has allowed companies to mark up prices and increase profit margins. The Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, has said that "corporate pricing decisions in a pandemic-distorted environment are a propagator of inflation." P&G declined to comment and Kimberly-Clark didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Those two companies — which in 2021 accounted for 63.1% of the US period-care market, according to Euromonitor International — largely manufacture their products in North America. But many startups in the category import goods, which brings its own challenges.

TOP, a company founded in 2018 that makes menstrual products with 100% organic cotton, has seen overseas shipping prices go from $3,000 to about $12,000 per container over the past six to nine months, co-founder Denielle Finkelstein said.

Unequal Access

The mix of disruptions adds up to more hardship for shoppers, particularly those on the lower end of the income scale. At Target.com, a box of 36 Tampax Pearl tampons sells for $9.59 while a package of Kimberly-Clark’s U by Kotex Pads, with 44 ultra-thin pads, goes for $7.29.

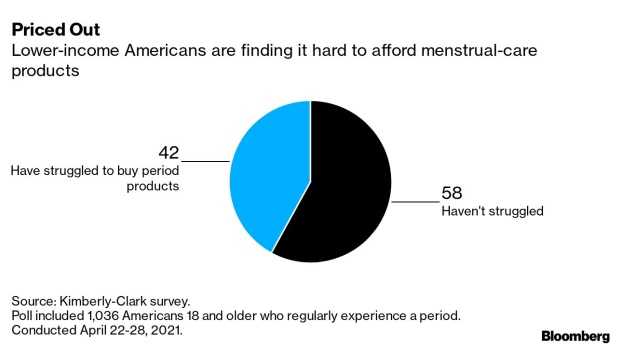

Even before the latest price jumps, two in five people said they struggled to buy period products, a 35% increase from 2018, according to an April 2021 survey by Kimberly-Clark. The consequences can be serious: One-third of the low-income respondents said they had missed work, school or similar events due to lack of menstrual supplies.

While some consumers have traded down to store-brand products to save money, others are scaling back on their consumption, in some cases by purchasing more heavily absorbent pads or tampons, said Liying Qian, senior research analyst at Euromonitor.

Using period products for longer than recommended can lead to discomfort, irritation and, in severe cases, infections.

Companies such as Walmart Inc., Target Corp., CVS Health Corp. and Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. that offer store brands could benefit from the shift to less expensive products. At the same time, for firms marketing premium goods with features such as organic cotton, it’s becoming more important to communicate their benefits as prices rise, Qian said.

Price pressures have pushed more women to turn to organizations that supply free menstrual products. At TOP, Finkelstein said bulk orders grew 500% year-on-year, many coming from community groups that provide period goods to those in need.

But nonprofits can’t get their hands on as many pads and tampons as they used to because of rising prices and high shipping costs that make it harder to deliver supplies to local distributors. In early May, a backlog of requests forced menstrual-care nonprofit PERIOD. to temporarily stop taking product orders from community organizations.

“Shipment costs are extreme, and it’s not just for us. It’s also for the companies that donate to us,” said Michela Bedard, executive director of PERIOD. “Typically a lot of companies would cover the cost of shipping when they would donate products to us. Now, more and more, we’re seeing that companies are asking us to pay for the shipping.”

Federal assistance plans including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program don’t cover personal-care products such as pads and tampons, making them difficult for the neediest people to obtain. Moreover, unlike many other basic necessities, they’re not tax-free in most US states.

“Period poverty has a solution,” Bedard said. “The solution is policy surrounding making more products more affordable by repealing the tampon tax and also by mandating them for free at schools and other public places.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.