Feb 4, 2022

It’s Taken a Pandemic to Get the Boardroom in Touch With the Workforce

, Bloomberg News

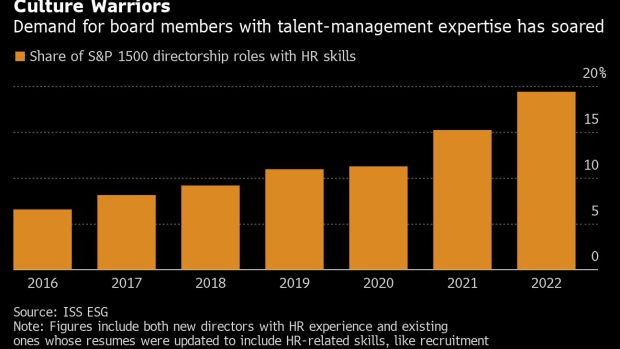

(Bloomberg) -- Companies often say that employees are their most important asset, but you’d never know that by looking at corporate boards. Directors largely come from the ranks of current and retired CEOs, finance chiefs, lawyers and investors, with a smattering of academics thrown in. What you rarely found in the boardroom were human-resources experts.That’s changing. With workers quitting jobs at a record clip and corporate cultures convulsing over issues like remote work, burnout and diversity and inclusion, boardrooms are opening the door to more directors with actual experience managing workforces. The share of directorship roles across all companies in the S&P 1500 with specific human-resources skills increased to 19.4% in January from 11.3% two years ago, according to ISS ESG, the responsible-investing arm of Institutional Shareholder Services. Talent management now tops the list of areas that need more time and attention in the boardroom, beating out strategy oversight for the first time, a director survey from PricewaterhouseCoopers found.

“Talent is the primary differentiator a company has,” said Tierney Remick, vice chair and co-leader of the board and CEO practice at executive recruiter Korn Ferry. “So having a voice in the boardroom that understands the talent equation and the future of work is critically important.”Recent examples include Steven Mizell, Merck & Co.’s HR chief, who joined two boards in the past two years; Stephanie Lundquist, the former chief HR officer at Target Corp., who’s on the board of food distributor Sysco Corp.; Frank Lopez, the HR chief at Ryder System Inc., who’s now a director at commercial landscaping company BrightView Holdings Inc.; and Ellyn Shook, Accenture’s chief leadership and HR officer, who just joined a corporate board last month.

There are catalysts beyond the pandemic’s labor crunch. The broader, ongoing push to diversify boards by adding more women and under-represented minorities has had a knock-on effect of widening the candidate funnel to include people from more varied functional backgrounds, like human resources. The new board members listed above all have one thing in common: They’re not white males. The number of S&P 500 seats held by Black women increased by more than 25% last year, and some of them come from the HR arena, according to Bonnie Saynay, managing director and global head of ESG research and data strategy at ISS ESG.

On top of that, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission required last year that public companies disclose more information on their workforces in annual filings, including a description of “human capital measures or objectives” that matter to its business. Until then, the only labor-related data companies consistently reported in their 10-Ks were the number of people they employed.

The shift is long overdue, according to industry experts. Boards have historically dealt with issues like compensation and succession planning, topics that HR pros are well-versed in. But they weren’t joining boards because there was invariably a more in-demand skill that boards were after, like digital transformation, which has been all the rage in recent years. More recently, cybersecurity has become hot as well. That helps explain why, as recently as 2019, fewer than 3% of directors at Fortune 1000 companies were either current or former HR executives, Korn Ferry data show.

“People with HR experience should have been on boards long ago,” said Laurie Siegel, a former HR executive at Honeywell International Inc. who serves on two boards. “But it’s great to see it happening now.”

It comes at a critical junction. A recent PwC survey of more than 650 c-suite executives cited the ability to hire and retain talent as both the most important factor and the biggest risk in reaching their organizations’ growth goals in 2022. Managing increasingly hybrid workforces, redesigning offices to make them more of a destination and adding resources to battle employee burnout are now strategic imperatives, putting them squarely on the board’s agenda.

“One of the central obligations of the board is to assess risk,” Siegel said. “A decade ago, if you sat through a risk assessment, talent or people were barely mentioned—and if they were, it was just words on a chart. Now, we know how much risk there is for companies in not being able to protect and retain their workforce, and they’re now just beginning to become obvious to boards.”

Still, it’s not obvious to every board. Gretchen Crist, a recruiter for RSR Partners and a former HR executive at Altria Group Inc. and Nestle SA, has been on the board of Hostess Brands Inc. since 2018. Crist said many small and mid-size companies, where she does most of her recruiting, are still reluctant to place an HR executive on the board.

“It’s pretty shocking to me that more and more boards aren’t looking specifically for CHRO talent,” she said, using the acronym for chief human resources officer.

Whether the new HR-focused directors have the ear of the CEO is unclear. Siegel, who ran HR for Tyco International in the wake of Chief Executive Officer Dennis Kozlowski’s dismissal and prosecution for looting the company, said it’s important to have a point of view on all aspects of the company’s operations, not just workforce issues. Siegel pushes her boards to do town halls with employees, so they can get exposure to a range of opinions, not just the view from the c-suite. She also encourages high-performing staff to present their best ideas to the board from time to time.

“The world has changed, so that’s why it’s good to have someone on the board who can think about and understand company culture,” said Julie Daum, leader of Spencer Stuart’s North American board practice.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.