Jul 29, 2022

Japan’s Youth Shun Politics, Leaving Power With the Elderly

, Bloomberg News

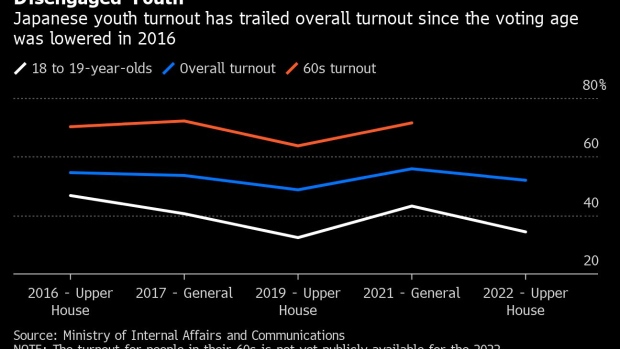

(Bloomberg) -- The murder of Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe just days before the upper house election sent shockwaves through the nation. Yet voter turnout increased only marginally and Japanese youth remained largely disengaged.

With just 34% of 18- and 19-year-olds heading to the ballot box, youth turnout relative to the overall figure was the lowest since the voting age was dropped from 20 to 18 six years ago. That’s despite an ongoing civic education campaign aimed at rallying younger Japanese, who trail counterparts in the US and Korea in political engagement.

With the world’s oldest population, Japan is facing a “silver democracy” crisis in which the younger generation feels underrepresented in politics, despite shouldering an ever-increasing burden to support the non-working population. The low youth turnout was a far cry from the 64% of Japanese in their 60s who hit the booths in 2019. Data for that age group in this month’s election is not available.

Unless that gap narrows, experts say policies will continue to favor the elderly and are less likely to be socially progressive. The conservative Liberal Democratic Party, which has held power almost continuously since its formation in 1955, opposes same-sex marriage or allowing married couples to have different surnames. Critics say it has dragged its feet in advancing the rights of women.

“Democracy shouldn’t have to be dependent on one’s age,” said Momoko Nojo, founder of “No Youth No Japan,” an activist group with over 100,000 followers on Instagram. “When you look at the reality right now, the values that are important to 18- and 19-year-olds and those in their 20s are not really reflected in society.”

Since Japan lowered its voting age in 2016, the government has sought to boost youth engagement through civic education. In the days leading up to the ballot, Tokyo’s Nogyo High School, for instance, allotted class time for its third-year students to take part in online quizzes that offer voters a snapshot of their compatibility with each political party.

“Younger students tend to think very deeply, and if they can’t decide on a party, a lot of the time they just don’t go to the voting booth,” said Eriko Hanawa, a social studies teacher at the school. “I think it’s important to explain to them that some adults don’t even know everything about the election, but what’s important is to show up.”

The Japanese media published a swathe of such online questionnaires, called Voting Advice Applications, that run people’s policy preferences through an algorithm and serve up a recommended vote. With an abundance of clickable links directing people to information about parties and their policies, the quizzes prompt people to engage in further research.

Despite such efforts, campaigners say young people feel unable to challenge the status quo, or are often actively discouraged from political debate. In a case that went viral on Twitter, a student at Miyagi Prefectural Sendai Daini High School in Tohoku was forced to take down information posters on how to vote when the teacher said they were too political.

“That’s probably not so exceptional,” said Masahisa Endo, an associate professor of political science at Tokyo’s Waseda University. “Teachers are very sensitive to political issues in schools.”

Despite expectations that Abe’s shock killing could rally voters, turnout among 18- and 19-year-olds was just 2.2 percentage points higher than the last upper house election in 2019. The overall turnout rose 3.3 percentage points to 52%, according to data from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

In the 2020 US presidential election, 51% of the 18-24 age bracket voted, while the turnout for 19-year-olds in the 2017 presidential election in South Korea was close to 78%.

Policy change, such as the governing LDP phasing out coal-fired power generation, is less likely unless younger people become more politically active, said Endo.

“The so-called Generation Z pays more attention to climate change or other issues than other generations and such voices may be less reflected in political processes,” he said.

Digital Minister Karen Makishima said that it was the role of lawmakers to boost participation in the electoral process, and online voting could help.

“We’d like to promote young people’s interest in elections and democracy,” she told a briefing in Tokyo this week. “As a parliamentarian, I’m interested in having more ways, easy ways for people to access ballots.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.