Mar 16, 2019

JPMorgan Hack Suspect Is Helping the U.S. Here's What He May Offer

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- He’s the accused mastermind of one of the biggest hacks ever. He and his crew allegedly pilfered information from more than 80 million JPMorgan Chase & Co. clients and ran online gambling, stock manipulation and money laundering schemes around the world.

Gery Shalon, charged with those crimes four years ago, has rarely appeared in court since he was extradited to the U.S. Now it’s clear why: Shalon is helping U.S. authorities, according to people familiar with the matter.

Such cooperation could result in anything from a lighter sentence to outright release. That would be a remarkable turnabout for a man who Loretta Lynch, then the U.S. attorney general, accused of netting hundreds of millions of dollars from “one of the largest thefts of financial-related data in history.”

Because authorities singled out Shalon as the brazen scheme’s leader, he would have to deliver something important to chip away at his 23 counts, several of them carrying potential 20-year prison terms.

While the precise nature of his cooperation isn’t clear, Shalon intersected with worlds that later came under the glare of some of U.S. history’s most politically charged investigations. An Israeli citizen, he allegedly teamed up with a Russian hacker who is now also in U.S. custody, raising the prospect that Shalon could provide U.S. prosecutors with a road map to Russian cyber crimes, how criminal hackers interact with that country’s intelligence services, or both. Other alleged Russian cybercriminals have been brought to the U.S. and charged, among them potential cooperators.

Judging by the range of activities outlined in Shalon’s indictment, he may also be able to act as a guide into criminal spheres such as international money laundering.

A release of Shalon would be “pretty extreme,” said Rebecca Roiphe, a professor at New York Law School and former Manhattan prosecutor who isn’t involved in the case. “He must be giving up somebody who is far more culpable than him, either in this crime or in a coordinated crime, to get that deal.”

If he’s cooperating, she added, “there may be something coming down the road that will answer this riddle."

A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan declined to comment. A lawyer for Shalon didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Father Speaks

The prospect of a light sentence for Shalon was raised recently by his father, Shota Shalelashvili, a lawmaker in the Republic of Georgia. In an interview on Georgian television last month, Shalelashvili hinted his son could soon be released from U.S. custody after explaining how he carried out the hack and repaying “millions” in stolen money.

Shalon has been allowed to remove his home monitoring device, his father told Georgian television, indicating he was at some point allowed to move from jail to home confinement.

Shalelashvili didn’t respond to requests to comment about the TV report.

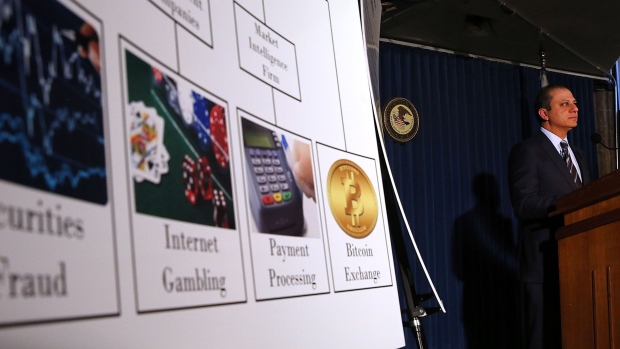

Shalon’s alleged hacking conspiracy had tentacles across a wide swath of the global financial system and encompassed identity theft, pump-and-dump frauds, illegal Internet casinos and money transfers via an illegal cryptocurrency exchange. Victims of the hack included Fidelity Investments, E-Trade Financial Corp. and Dow Jones & Co.

The breach of sensitive systems inside JPMorgan was so vast that U.S. intelligence officials initially feared there might be a connection to Russia’s spy agencies, and they provided the FBI with evidence of possible links, according to a U.S. law enforcement official. Ultimately, the FBI said the endeavor was purely criminal.

At a minimum, authorities might enlist Shalon to explain how his crew and other hackers managed to launder hundreds of millions of dollars, which could help them track the vast money trail of modern-day cyber theft. Prosecutors could also have put Shalon back online, as they have in other hacking cases, using him as a guide through the criminal underground and perhaps even luring other cyber-criminals into U.S. grasp.

Moving to Israel

In his interview with Georgia’s Rustavi 2 television channel, Shalelashvili said his son could be allowed to present financial guarantees that could let him leave the U.S. “He may be found guilty -- but not to the extent that may have been expected,’’ the father said.

Shalelashvili, 59, was born in the then-Soviet republic of Georgia and moved as a young man to Israel, where he raised his family. He now has Georgian, Russian and Israeli citizenship, and has said in previous interviews that he made much of his fortune doing business in Russia and Africa. In 2014, Shalelashvili made a run at buying Georgia’s Cartu Bank from billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili for $270 million. Ivanishvili, a previous prime minister, pulled out of the deal.

Gery Shalon was arrested in July 2015 at his home in a Tel Aviv suburb. He was extradited to the U.S. in 2016. That same year, his father returned to Georgia and gained a seat in the country’s parliament as a member of Ivanishvili’s party, Georgian Dream, which currently holds the majority.

Shalon had $100 million stashed in Swiss bank accounts at the time of his arrest, according to U.S. officials. He and his main co-defendants agreed to a series of deals repatriating money stashed in bank accounts in Switzerland, Georgia, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Latvia.

U.S. authorities also asked Georgian officials to seize Georgian accounts held by Shalelashvili, according to the television report. Shalelashvili told the TV interviewer that Georgian authorities misidentified money in his accounts as belonging to his son and later released it. The office of Georgia’s prosecutor declined to comment.

In all, Shalon agreed to surrender $403 million in 2017 as part of the case, Israel’s Calcalist newspaper reported, citing court documents it reviewed. Many of the documents in Shalon’s case file in Manhattan federal court remain sealed.

As several of Shalon’s alleged co-conspirators pleaded guilty or were tried and convicted, Shalon quietly idled in the U.S. legal system. Public hearings have been repeatedly postponed. The long delays and silence are typical when a defendant turns into a cooperator.

Georgia Arrest

All the while, a key alleged co-conspirator remained at large -- an unidentified, Russian-speaking hacker who authorities said had hands on the keyboard to penetrate networks for Shalon’s ring. Then, in September, federal prosecutors heralded a “significant milestone’’ in their case: The JPMorgan hacker, whom they identified as Andrei Tyurin of Russia, had been arrested in the Republic of Georgia and extradited to the U.S.

The U.S. and Georgia don’t have a formal extradition treaty, but they have had a general law enforcement cooperation agreement for nearly two decades. How and why Tyurin wound up in Georgia remains unclear. Georgian authorities said he was arrested entering the country through Tbilisi International Airport, and said he was unaware that he was a wanted man.

For U.S. officials, Tyurin could help illuminate the links between Russia’s cyber criminals and its spy agencies. During the JPMorgan investigation, U.S. intelligence agencies presented the FBI with evidence that Russia had tried to recruit the hacker, who was initially referred to in the indictment as co-conspirator 1.

According to Georgian authorities, Moscow mounted an unsuccessful bid to have Tyurin returned to Russia.

Tyurin appeared at a hearing immediately upon arriving in the U.S. and again a few weeks later. Subsequent hearings in his case have been postponed, like those for Shalon over earlier years. A lawyer for Tyurin didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Shalelashvili, in an interview with Bloomberg, said he was aware of Tyurin’s arrest in Georgia but had no knowledge of how it came about.

Read more: Digital Don Accused of Hacks at JPMorgan, Dow Jones Over 8 YearsJPMorgan Hack Suspect Leaves Russia to Face U.S. ChargesU.S. Crackdown on Russian Hackers Ensnares Notorious Spammer Russian Spam King Pleads Guilty in Win for U.S. Prosecutors

--With assistance from Jonathan Ferziger and Jordan Robertson.

To contact the reporters on this story: Helena Bedwell in Tbilisi at hbedwell@bloomberg.net;Christian Berthelsen in New York at cberthelsen1@bloomberg.net;Michael Riley in Washington at michaelriley@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeffrey D Grocott at jgrocott2@bloomberg.net;Gregory L. White at gwhite64@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.