Fancy Apartment Rentals for Paris Olympics See Poor Demand and Price Cuts

Locals who’d hoped to turn a big profit by renting out their posh apartments are now slashing prices by 30%-60%.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Locals who’d hoped to turn a big profit by renting out their posh apartments are now slashing prices by 30%-60%.

The kingdom must overcome a conservative image and concern about human rights. Visit the desert oasis town of AlUla to understand the challenge.

Jury selection was completed Friday for Donald Trump’s first criminal trial, setting the stage for opening arguments Monday in a New York case accusing the former president of falsifying business records to conceal a sex scandal before the 2016 election.

Higher-than-expected interest rates amid persistent inflation are perceived as the biggest threat to financial stability among market participants and observers, according to the Federal Reserve.

Fifth Third Bancorp jumped the most in four months, leading bank stocks higher, with Chief Executive Officer Tim Spence predicting that income from lending has bottomed out.

Apr 5, 2021

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- South Koreans’ anger over soaring home prices and yawning wealth inequality is fueling support for opposition candidates in by-elections seen as crucial for maintaining momentum in President Moon Jae-in’s economic agenda.

While an overheated housing market has become a global phenomenon from Australia to Canada amid a flood of stimulus, its political implications look set to come to a head in Korea on Wednesday when voters go to the polls in mayoral elections in the capital Seoul and the southern port of Busan.

As Moon’s popularity continues to plumb new lows, losing both key cities to opposition candidates could mark a turning of the tide against Moon’s flagship economic policies including his plans to increase public employment and a push for larger fiscal spending as he enters his last year in office.

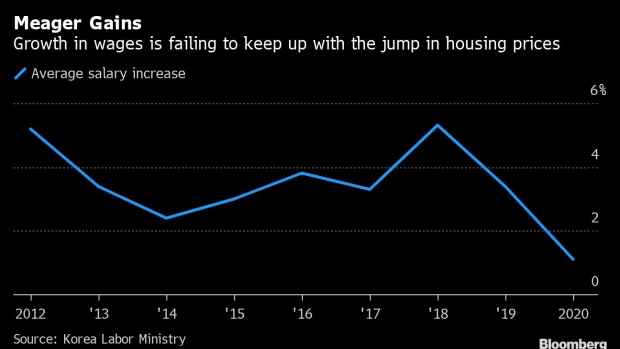

The discontent centers on a lack of affordable housing despite Moon’s pledge to deliver more when he was elected in May 2017. Apartment prices in Seoul have doubled in the last five years, while Korean salaries have risen less than 20%, leaving housing in the capital out of reach for many people and some of it in the hands of a speculative few.

Moon has enacted dozens of measures to curb gains, only to see some of them backfire and prices in Seoul surge further during his term. Adding to the discontent are allegations that scores of officials handling land properties may have used insider information to profit from city development projects.

Polls conducted before the blackout period show the conservative camp’s Oh Se-hoon is poised for a landslide victory against ruling party heavyweight Park Young-sun in Seoul.

Average monthly wages at companies were 3.5 million ($3,092) won last year. That compares with an average apartment price in the capital of 1.09 billion won ($970,000) in March, up from 607 million won in May 2017, according to prices compiled by KB Financial Group.

While the housing squeeze is most acute in the capital where prices gained a further 13% in 2020, it also plays out on a national level, with apartment prices across the country rising 9.7%.

Korean households owe more money than ever before as they race to purchase homes before prices go even higher. Their debt has now reached 175.5% of disposable income. The rise has been fueled by mortgages to buy or rent homes, despite strenuous efforts by the government to make it harder to take out loans to tamp down speculative investment.

If lending rates on household loans rise by just 8 basis points, that could raise interest payments by 416 billion won, with around a half coming from housing-related loans, according to the Bank of Korea.

The problem extends beyond out-sized mortgages to large deposits people need just to rent a home. Tenants need to take out loans to cover so-called jeonse deposits that enable them to live in a home for a period of usually two years or longer often without monthly payments.

By stumping up lump sums worth as much as two-thirds of a property’s price, tenants are essentially borrowing to provide landlords with free loans to invest more.

Park has tried to express her unhappiness with Moon’s real-estate policy and distance herself from the president, whose own approval rating hit a record low of 32% on Friday. She has called for more public ownership of housing developments.

Meanwhile, Oh has criticized Moon’s party for tightening regulations on redevelopment and limiting the number of building permits over the years, saying the attempt to rein in gains by private constructors have backfired.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.