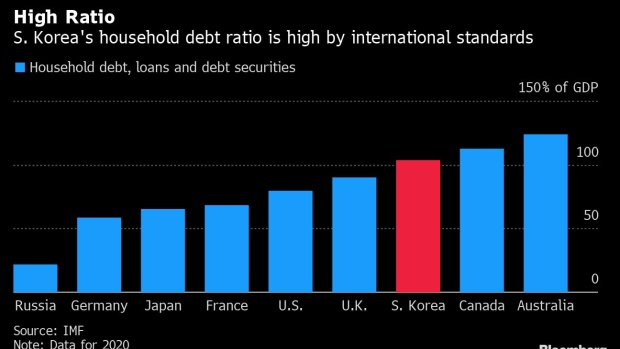

(Bloomberg) -- South Korean households have a serious debt problem: They’ve got one of the world’s biggest borrowing burdens and that’s prompting banks to sell bonds to protect their balance sheets if a crisis causes the loans to go bad.

As Koreans boosted borrowing to get a piece of the nation’s red-hot housing market, their debt climbed above 1,000 trillion won ($834 billion) for the first time last year. That total exceeds the nation’s entire annual economic output, at 103%, compared with Japan’s 65% and U.S.’s 80%, according to International Monetary Fund data.

It’s a debt pile that Fitch Ratings says “stands out” among its global peers, and “has exposed banks to a greater susceptibility to a severe economic shock.” Korea’s biggest lenders are responding by seeking funds in the debt market to bolster their capital at a time when rising interest rates also pose risks for them.

Shinhan Financial Group Co. this month priced 600 billion won of additional Tier 1 notes that count as capital and carry the risk of being written off first should the lender’s balance sheet deteriorate to a point of non-viability. Hana Financial Group Inc. sold 270 billion won of similar debt, while KB Financial Group Inc., Meritz Financial Group Inc. and Woori Financial Group Inc. also plan to sell such notes next month.

While the so-called contingent convertible notes, or CoCos, are considered the highest-risk debt that banks sell, their elevated yields draw investors. The Korean borrowers have also been redeeming their domestic bonds at the first opportunity they had the option to do so, avoiding investment risks from longer maturities.

Shinhan Financial’s perpetual notes that can’t be called for five years paid 3.9%, for example, compared with an average yield of around 2.9% for five-year Korean corporate debt.

“CoCo bond sales by Korean banks or financial holding companies will continue for a while given their need to raise capital buffers after household loans soared last year,” said Han Gwangyeol, credit analyst at NH Investment & Securities Co. in Seoul. “It’s a good deal for investors, especially retail investors, given their AT1s are usually called after five years with a coupon of around 4%.”

Korea’s inflation-adjusted residential house prices rose for the 23rd straight month in December, according to Bloomberg calculations using official figures. The surge in housing costs has hit middle-class Koreans and has been cited as a top factor for voters who disapproved of President Moon Jae-in.

However, Bank of Korea rate hikes and government regulations are starting to curb borrowing, with monthly gains in the nation’s mortgage loans cooling to more than a three-year low in November.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.