Jul 4, 2022

Lagarde’s Task Toughens as Nagel Fires Salvo on ECB Crisis Tool

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

The days of European Central Bank teamwork heralded by Christine Lagarde may be ending as a Bundesbank warning shot on her crisis policies evokes its prior role as a thorn in the presidency’s side.

The public salvo on Monday by German official Joachim Nagel, cautioning on the dangers of an anti-turmoil tool, is raising the temperature just as discussions intensify on a key pillar of the ECB chief’s plans to raise interest rates.

In a possible echo of the ordeal her predecessor Mario Draghi faced during the sovereign-debt crisis a decade ago, Lagarde might now face the task of executing a tricky policy maneuver fraught with the danger of market turmoil -- all while worrying about the prospect of a critical German central bank.

The comments reflect “the difficulty in designing such a tool, especially in terms of the trigger for intervention,” said Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management. “It may also be politics in the sense that you need to sell the tool at home. After all, the president of the Bundesbank has to state his objections.”

The abrupt departure last year of Nagel’s predecessor, Jens Weidmann, already hinted at difficulties, but the new Bundesbank president had until now stuck a more diplomatic tone when discussing ECB policy in public.

What changed was the outbreak of debt-market turmoil in June focused around Italy, precipitating a pledge by the Governing Council to develop a crisis tool intended to allow the very rate hikes sought by the Bundesbank to proceed unhindered.

Strict Terms

Nagel’s speech suggests that the likely shape of such an anti-turmoil measure, and the speed with which Lagarde shifted stance, were too much to stomach.

“Monetary policy must not be driven by what are often very short-lived developments in the financial markets,” he said. “Unusual monetary policy measures to combat fragmentation can be justified only in exceptional circumstances and under narrowly-defined conditions.”

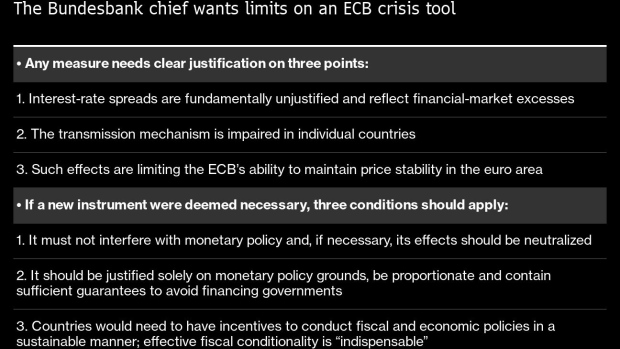

Nagel set out strict terms where such a tool could be justified, tough conditions when its use could be conscionable, and the warning that otherwise, “one can easily find oneself in dire straits.”

The language used chimed with legal concerns on bond purchases aired by Germany’s constitutional court, where the validity of any instrument may well ultimately be tested.

An hour later, ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos, in his own scheduled appearance at the same conference, sought to reassure that any use of a tool wouldn’t be indiscriminate -- holding out the prospect that any measure will be appropriate.

“We will react to prevent fragmentation, with suitable safeguards to prevent moral hazard,” he said. “Our commitment to fight fragmentation should thus not interfere with, but rather enable, a greater focus on the monetary policy stance.

Conceivably, an ECB tool could just meet the conditions set by Nagel, though his remarks may well set the scene for major disagreements ahead.

The Bundesbank chief’s speech provides a glimpse into the hawks’ “red lines,” but such conditions can help support the ECB’s credibility and avoid market turmoil down the line, Allianz SE economist Katharina Utermoehl said. “After all, it would be of little use to put forward a no limits spread fighting tool which only enjoys a short shelf-life.”

Bundesbank Tradition

Nagel’s intervention follows in his institution’s long tradition of seeing itself as a guardian of price stability, a role on which the ECB was then modeled. Inherent in that is a prohibition against monetary financing set in stone in an EU treaty.

Against that backdrop, Bundesbankers have frequently protested ECB policies. One president, Axel Weber, quit in 2011 as the euro-zone central bank bought up bonds of turmoil-stricken countries such as Greece. Juergen Stark, the ECB chief economist and a former Bundesbank official, resigned later that year.

Meanwhile Weber’s successor, Weidmann, testified in court against the OMT crisis-fighting tool that Draghi unveiled in 2012. He later accepted its validity when in the running himself to lead the ECB.

The advent of Lagarde as president turned a new page. She took a more conciliatory approach than that of Draghi, and both Weidmann and Nagel had largely played along.

In an interview just before taking office in 2019, she explained her priority as “making sure that we are a team, that we disagree amongst ourselves and then, once the disagreement is settled, once there is a common line, that we all move together.”

It’s hard to square Nagel’s public intervention with that approach. This episode doesn’t yet constitute a full breakdown in relations, but with the likelihood that German public opinion could take note, that danger is now coming into view.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.