May 20, 2022

Lebanon’s Bond Restructuring Faces More Delays After Election

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for our Middle East newsletter and follow us @middleeast for news on the region.

Lebanon’s creditors are bracing for an even longer wait for a debt restructuring deal after an inconclusive parliamentary election cast more doubt about the country’s ability to deliver reforms needed to unlock crucial International Monetary Fund aid.

With no alliance winning a clear majority in Sunday’s elections, it’s not clear the deeply divided legislature can quickly form a new government, let alone bolster efforts to gain IMF cash. A deal with the Washington-based lender is seen as a prerequisite for a restructuring that could benefit bondholders.

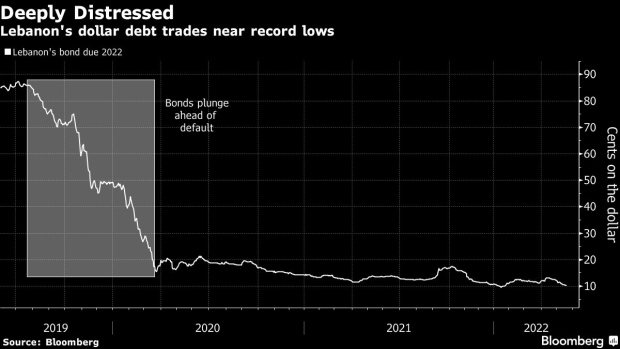

Two years after default, Lebanon’s international bonds are languishing near record lows of 10 cents on the dollar, down about half a cent since before the vote. Counting the $9 billion of debt in arrears, the government estimates that a total of $37 billion worth of Eurobonds is included in the scope of the restructuring.

“Significant reforms are likely to continue to be very difficult to implement,” said Ida Andreasen, a Copenhagen-based portfolio manager at Nordea Asset Management, which holds the nation’s bonds. The restructuring will take “a longer time due to the political uncertainty inherent in the country.”

Restoring Credibility

Lebanon has so far made little progress in meeting conditions of a preliminary agreement with the IMF. The country is banking on a $3 billion loan to overcome one of the world’s worst financial crises, help restore its credibility with investors and potentially unlock further foreign aid.

For the agreement to move forward, the IMF wants Lebanon to take several steps, ranging from an externally-assisted evaluation of each of the largest lenders to an audit of the central bank and the lifting of banking secrecy laws. The country also needs to unify multiple exchange rates used during the crisis.

The elections were the first since Lebanon’s economic meltdown began in 2019. Political parties now need to agree to a coalition government, a process that could take months especially after the Iran-backed Hezbollah group and its allies lost their majority in the legislature.

The end of President Michel Aoun’s term in October also risks further delays. The presidential seat was vacant for two years before parties agreed to nominate Aoun.

“The election results do very little to lift the fog over Lebanon’s policy making,” said Mohieddine Kronfol, the Dubai-based chief investment officer for Middle Eastern and North African fixed income at Franklin Templeton, which doesn’t own Lebanese debt. “Uncertainty has increased, as parliament is more fragmented, politics more polarized.”

Hans Humes, the founding partner of New York-based hedge fund Greylock Capital Management, which also has Lebanese debt, said a deal with bondholders would be easiest to achieve by a “fully-functioning” government.

“It’s important that the IMF’s prior actions are implemented before restructuring talks start,” he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.