(Bloomberg) -- Lance Paul put his home in West London on the market last May with a 1.5 million-pound ($2 million) price tag. A year on, the retired animator is asking 1.1 million pounds and still hasn’t found a buyer.

Now, after dozens of viewings that came to nothing and a few low-ball bids, the 71-year-old has an offer that’s agonizingly close to the floor he promised himself he would never go below. He just might accept it.

“The fear from my point of view is because things are volatile, it could go down even further,” Paul said.

London housing: Read the experts on the outlook for prices

Similar deliberations are playing out across London as sellers weigh whether to take what they can get in a falling market or sit tight in the hope the slump will be short-lived. For most of the past four decades—through Tory and Labour-led governments and across financial booms and busts—sitting tight proved a wise course. The question now is whether Brexit and the gradual withdrawal of easy-money policies around the globe will turn the current stumble into something much worse.

“The party is over for the London housing market and the hangover is just beginning,” said Neal Hudson, founder of research firm Residential Analysts. “Lower demand due to Brexit or interest-rate rises could put further pressure on some home-owners and investors to sell.”

Since 1973, the year Britain joined the European Union, the average London home price climbed from just under 13,000 pounds to about 474,000 pounds—a 36-fold increase, according to Nationwide, the U.K.’s largest building society. The last big reversal occurred during the financial crisis, when prices dropped about 20 percent. Since bottoming out in 2009, they’ve nearly doubled.

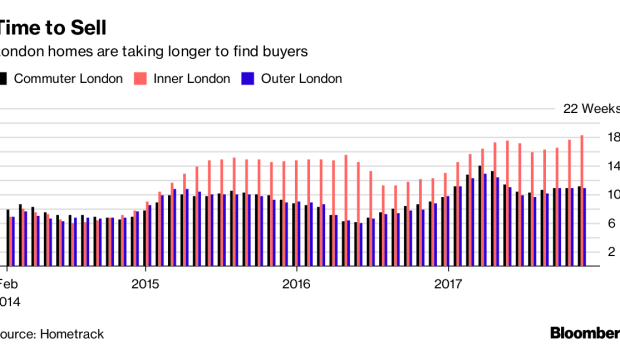

The declines this time have been modest. London recorded its first annual decrease in prices in more than eight years in February, a drop of 1 percent, government data showed. That said, pricier central districts registered sharper falls and forward-looking indicators, such as the time it takes to sell homes, point to further declines.

Pessimists fret that some of the pillars that underpinned the long London property boom—from rock-bottom interest rates to generous government support—are under threat.

In the U.S., 10-year Treasury yields have reached the highest in almost seven six years, narrowing the premium that real estate has commanded over bonds for the past decade. That dents the relative appeal of London property, especially for those from outside the country.

International buyers made more than half of home purchases in prime central London and almost a third in greater London in the second half of 2017, according to broker Hamptons International. Both overseas and U.K. investors who purchase homes to rent out have become an increasingly important part of the London market over the past decade, lured by higher returns on offer from rental property at a time of low interest rates.

“What happens to real estate if real interest rates go up? In the most simple form, values go down,” said William Hughes, managing director and global head of research and strategy for real estate and private markets at UBS Group AG’s asset management unit. “If the political situation in the U.K. causes the economy to struggle while global rates were to rise, then that would be a double whammy for London.”

Changes the government made over the past few years to deter property speculators could also weigh. The reforms included an increase in sales taxes on second-home purchases and the gradual elimination of tax relief for mortgage interest on rental homes, which will eventually disappear in 2020. One popular initiative that’s helped support the property market, the government’s “Help to Buy” loan plan, is slated to end in 2021, unless it’s extended again.

And looming over everything is the potential impact of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union. Less than a year from the planned exit date, the terms of that rupture remain as murky as ever.

“What happens if rents fall 20 percent because we had a bad Brexit and no one wants to come here?” said Richard Donnell, director of research and insight at Hometrack, which provides data and analysis on the property market.

The city has had a good run. London’s best districts have seen prices climb by more than 500 percent since 1989, according to an index published by broker Knight Frank LLP. That compares with an almost 350 percent increase in the average value of condominiums and co-ops in Manhattan in that period, data compiled by Miller Samuel Inc. show.

Not everyone sees Brexit, or even higher interest rates, upending the property market. The pound’s slump after Britons voted to leave in June 2016 cushioned the blow by making London homes more affordable to buyers from abroad. The prospect of a weaker currency remains an insurance policy against a disorderly Brexit, said Savvas Savouri, the chief economist at Toscafund Asset Management LP. He’s optimistic about the housing market and supports leaving the EU.

He does see one big political risk beyond Brexit, however: the potential ascension of Labour party leader and self-proclaimed socialist Jeremy Corbyn to the premiership. At last year’s general election, Corbyn promised to introduce rent controls, among other proposals that harken back to a less business-friendly era.

Should a Labour government materialize, “the pound will crash,” Savouri said. That would lead to “a genuine stampede” of capital out of the U.K., he said.

All of these “what ifs” complicate matters for owners like Lance Paul, who’s considering the offer for his Shepherd’s Bush home. He wants to raise money for medical bills, to top up his modest pension and to move closer to his son, who was forced out of London by sky-high home prices.

“We want to move now—so we have to accept that if we hung on we could get more,” he said. “But I don’t think we would be out of this house for another three years.”(This is the first in a series of stories on the outlook for London's housing market as it runs out of steam after almost a decade of growth.)

--With assistance from Sharon R Smyth.

To contact the author of this story: Jack Sidders in London at jsidders@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Frank Connelly at fconnelly@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.