Aug 6, 2020

Long-Short Hedge Funds Are Necessary, Not Evil

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Even a global pandemic has failed to curb investor enthusiasm for stocks, with the MSCI World Index of global equities about unchanged for the year after rallying hard from its March lows. As a result, short sellers who seek to profit from declines are becoming an endangered species. But their extinction would be a bad thing for financial markets.

In a short sale, a fund borrows stock from a broker or bank and sells it at the prevailing market price, betting that a decline will allow it to return the shares to the lender after repurchasing them at the new, lower value so they can pocket the difference. The rising global stock market tide, however, has been lifting all equity boats for several years, while the 2020 flood of central bank money designed to ameliorate the economic impact of the novel coronavirus is keeping zombie companies alive for longer.

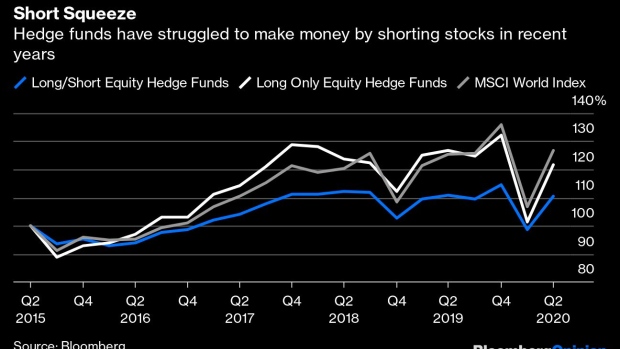

In the past five years, hedge funds pursuing a long-short equity strategy have gained about 10%, less than half of the gains available from either long-only funds or from a simple tracker based on the MSCI World Index of global stocks.

So it’s little wonder that investors are shunning the strategy. Data compiled by eVestment show long-short hedge funds suffered withdrawals of $4.65 billion in June, the worst among the ten primary hedge-fund strategies the research firm tracks. That extended first-half outflows to more than $11 billion, after clients already pulled more than $44 billion last year.

Short sellers serve a vital market function. They are financially motivated to uncover malfeasance in an industry which is otherwise skewed away from negativity, either by companies seeking to put a positive spin on their news and data, or by compliant analysts who are all too often in thrall of their investment bank colleagues seeking to win business from the companies they cover. To be sure, not every short seller is correct when they question a company’s accounting propriety, nor are their motivations in doing so always pure and untainted.

But painting short selling as an unalloyed evil, as some market participants have tried to do, is misguided and unhelpful. The financial misadventures of German electronics payment company Wirecard AG, for example, would probably have gone unnoticed if it wasn’t for the dogged pursuit of the truth by short sellers, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Chris Bryant noted in June.

“The best short sellers rightly see themselves as crusaders for truth or as Robin Hood figures pitted against the stock market establishment,” Paul Marshall, the billionaire co-founder of Marshall Wace LLP, wrote in his recently published book, “10 ½ Lessons From Experience: Perspectives on Fund Management.” Marshall says it’s much harder to make money from short positions than from simply owning a stock. The drawbacks include the costs involved in going short, the prevalence of bull versus bear markets in the past 50 years, and the increased volatility that accompanies “shorting a company in its death throes.”

He has figures to back up that assertion. The Eureka fund he oversees as part of the $44 billion his firm manages generated annualized excess returns of 8.79% from its long positions in the decade to the end of 2018, compared with just 2.81% from shorting stocks.

In a paper published last year by the Boston University Law Review, law professors Peter Molk and Frank Partnoy argued that short selling “has the potential to improve the efficiency and fairness of equity markets,” and that institutional investors such as pension providers and sovereign wealth funds should actively pursue the practice.

Moreover, hedge funds can help put pressure on companies to improve their environmental, social and governance practices, according to a recent report by the Alternative Investment Management Association, which represents more than 2,000 funds overseeing $2 trillion of assets.

Short selling, for example, can raise the cost of capital for companies that are failing to curb their carbon emissions, the AIMA argues. And given the paucity of reliable data on ESG issues, profiting from a short sale provides an opportunity for funds to be rewarded for uncovering misbehavior that might otherwise go unreported, the report says.

So here’s to the short sellers, and their continued existence as much-needed thorns in the side of the overhyped, overoptimistic or just plain corrupt companies whose financial feet they hold to the fire.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.