Jan 22, 2020

Maersk Jacks Up Fuel Surcharge as Shipping’s Biggest Expense Spirals

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s largest container shipping line is hiking up a fuel surcharge that it imposes to transport boxloads of goods across the world’s oceans after new environmental rules sent the industry’s biggest expense spiraling.

Most of the world’s ships were forced to switch to burning fuel that’s lower in sulfur this year, causing costs to soar as the global refining industry adjusts to the new regime. In parts of India, vessels are at risk of coming to a halt due to limited supplies. Meanwhile, some new fuels have been found to contain potentially dangerous sediment.

A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, which ships almost one in every five containers moved by sea, is to impose a fuel surcharge of $50 to $200 per box across trade routes, according to a notice on the company’s website. The world’s merchant fleet mostly switched to very low sulfur fuel oil, or VLSFO, from Jan. 1.

“Others will definitely take lead from Maersk and follow with their own surcharges,” said Rahul Kapoor, head of research at IHS Markit, Maritime and Trade. “It’s still early days how higher fuel costs would have a meaningful impact on trade volumes.”

In Singapore, the world’s biggest ship-refueling center, the price of VLSFO -- the fuel of choice for IMO 2020 compliance -- is now about $270 a ton more expensive than the old, high-sulfur variety. Marine gasoil, the other main product vessel owners can use to comply, is also expensive.

Kapoor’s expectation is that the fuel-cost surge will start to abate and -- eventually -- that should feed through into lower fuel surcharges.

Trade group BIMCO warned this month that higher fuel costs effectively mean higher costs of carrying out world trade, even if such hikes will be largely invisible to end consumers.

In practice, shipping companies can’t always pass on the additional costs if there’s excess transportation capacity in a fleet.

It currently costs $1,520 to transport a 40-foot box to Los Angeles from Hong Kong, according to data from Drewry Shipping Consultants. That’s 22% lower than a year ago.

“Container rates are under pressure,” Per Hansen, an investment economist at stock trader NordNet, said in a note. “If Maersk doesn’t succeed in moving the extra fuel costs over to its clients and/or if Maersk doesn’t get a reasonable return on its investments in scrubbers on selected vessels, there’s only one left to pay the bill: the company and thereby the shareholders.”

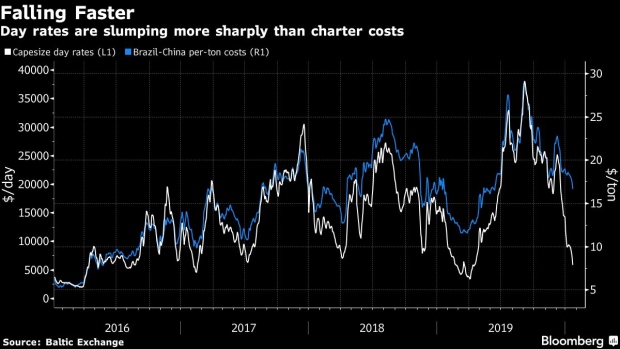

It’s a similar picture in dry-bulk freight markets where owners’ daily earnings have slumped more sharply than the per-ton prices that companies are paying to charter their vessels.

BIMCO said that persisting high fuel costs could create financial difficulties for some shipowners if the situation doesn’t improve. The Baltic Dry Index, a measure of commodity freight costs, slumped 9.6% on Tuesday.

--With assistance from Christian Wienberg.

To contact the reporters on this story: Firat Kayakiran in London at fkayakiran@bloomberg.net;Jack Wittels in London at jwittels1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alaric Nightingale at anightingal1@bloomberg.net, Rachel Graham

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.